Skilling Is Defiant on Stand

- Share via

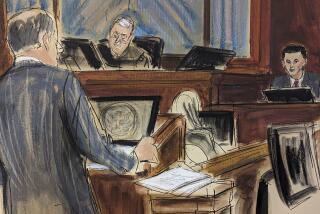

HOUSTON — The theme for Jeffrey K. Skilling’s fourth day on the witness stand was defiance.

The former Enron Corp. chief executive opened his testimony Thursday by claiming that the government had distorted the facts about Enron’s 2001 collapse. He ended the day by again declaring his innocence and promising to fight to clear his name and that of the energy company he helped build.

“Enron is now used as a term for everything wrong,” Skilling said. “Some day they’ll write the real books.”

The jury of eight women and four men will have the Easter weekend to ponder Skilling’s testimony. Meanwhile, co-lead prosecutor Sean M. Berkowitz will have three days to look for conflicts and weak spots in Skilling’s story as he prepares to begin his high stakes cross-examination Monday.

“It’s all going to turn on the cross-examination,” said Laura Ariane Miller, a partner at the firm of Nixon Peabody in Washington who is not involved in the case.

“The defense has put Skilling’s credibility totally at issue, so anything he’s said is fair game.”

Skilling, 52, and former Enron Chairman Kenneth L. Lay, who turns 64 on Saturday, face multiple counts of conspiracy and fraud. If convicted, they could spend decades in prison. The government alleges that they lied to the public about Enron’s financial condition and conspired to use accounting tricks to cover up losses and falsely inflate earnings.

Since taking the stand Monday morning, Skilling has repeatedly denied the allegations laid out by the prosecution during the trial, which began Jan. 30. On Thursday, while testifying about the government’s description of Enron’s fledgling retail energy and broadband trading units as “failing,” Skilling paused for a moment and said: “I’m sorry. I have to calm down here a little bit.”

His chief lawyer, Daniel M. Petrocelli of Los Angeles, asked why Skilling was upset.

“This is a total misrepresentation, in my view, of the state of events that were happening at that time,” Skilling said, adding that the businesses were poised to get through their rocky start-up phases and eventually become successful.

Several prosecution witnesses, including the one-time heads of the broadband and retail energy units, previously testified that by the spring of 2001, those businesses were dead in the water. They said Enron officials tried desperately to cover up the units’ woes because they were a big part of the “growth story” the company was selling to Wall Street.

The defense contends that Enron was in great shape in the fall of 2001 but its slide into bankruptcy was caused by a sudden loss of faith by creditors, akin to a run on a bank. The creditors, according to the defense, were spooked by erroneous media coverage stirred up by short sellers -- stock-market players who try to profit by betting that companies’ shares will fall.

Enron’s subsequent downfall threw thousands of people out of work and wiped out billions of dollars in stock market value and pension assets.

“I am devastated because the company was brought to its knees unnecessarily,” Skilling said Thursday. During his days as the firm’s No. 2 executive, he said, “I bled Enron blue.”

Enron’s collapse was bad enough, Skilling said, but “a lot of damage was done to people subsequently ... the result of a rewriting of history to accomplish certain objectives people have that are not consistent with what really happened.”

Outside the courtroom during a break in the trial, Petrocelli said that he and Skilling had worked ceaselessly to prepare for his testimony, but he denied that any of Thursday’s remarks were rehearsed. He said his client was “absolutely un-rehearsable.”

The jurors watched Skilling closely but without nodding their heads or otherwise betraying their sympathies. They haven’t always smiled at Skilling’s attempts at humor but they laughed Thursday when he cracked a joke about two broken-down Land Rovers he owns.

“You like working on cars?” Petrocelli asked.

“Yeah,” Skilling said. “That’s why you buy English cars. There’s always something to work on.”

The vehicles were mentioned during testimony about Skilling’s personal finances. He testified that he still owned $47 million in municipal bonds; an 8,500-square-foot, $4-million home in Houston; and a $350,000 condominium in Dallas -- all frozen by the federal government. Skilling said that money he set aside to pay his legal bills -- reportedly $23 million -- was already gone and that he still owed a large sum to Petrocelli’s law firm, O’Melveny & Myers.

Given his sometimes profane condemnation of the short sellers who were attacking Enron, it was surprising to hear Skilling also describe how he made $15 million in three or four weeks in August and September 2001 by selling short the shares of AES Corp., an international power company that competed with Enron in overseas markets.

Knowing that Enron’s foreign business was struggling at the time, Skilling said he was sure that AES would soon start posting weak earnings. He placed a massive bet against AES and saw it quickly pay off as the company’s shares tumbled.

The story came up when Skilling tried to explain his attempted sale of 200,000 Enron shares Sept. 6, 2001, about three weeks after his surprise resignation from the company. Earlier he said he didn’t remember the incident until his stockbroker testified about it during the trial.

The sale didn’t go through that day, but on Sept. 17 -- the first day the markets reopened after the World Trade Center attacks -- Skilling sold 500,000 Enron shares for $15.5 million. The sale is the basis of one of 10 insider-trading counts against Skilling; the government contends that he sold knowing that Enron was in trouble and its shares were likely to fall.

Skilling had told investigators at the Securities and Exchange Commission that his reason for selling was worry over the economy in the wake of the terror strike, but prosecutors at his trial pointed out that his first attempt came before 9/11.

Skilling said Thursday that the first attempt to sell was actually part of a strategy to hedge his bet against AES.

Although Skilling has had four days to present his version of events to the jury, he’s likely to face a tougher time Monday, when cross-examination begins. One of the dramatic high points of the trial came last month when defense attorneys cross-examined former Enron Chief Financial Officer Andrew S. Fastow, the government’s star witness, baiting him with personal attacks and peppering him with rapid-fire questions.

In his direct testimony, under friendly questioning by Petrocelli, Skilling needed to hit “a double or a triple” to counter the government’s strong case, Miller of Nixon Peabody said.

“We don’t know how he did,” she said, “because the ball hasn’t been fielded yet.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.