A ‘King’-sized collapse

- Share via

The ingredients all seemed to be there for Oscar-winning director-screenwriter Steve Zaillian. He had a cast of heavy hitters -- Sean Penn, Kate Winslet, Jude Law and Anthony Hopkins for starters -- and a classic story in Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “All the King’s Men.”

But when Zaillian’s version of Warren’s 1946 story of political corruption and personal betrayal hit the nation’s movie screens Sept. 22, it played to mostly empty theaters, drawing only $3.8 million in its opening weekend against a reported $55-million budget.

And Zaillian, who won an Oscar for his adaptation of “Schindler’s List” (1993), couldn’t even take solace in critical support. Reviewers generally panned the film, complaining about everything from Penn being miscast as a blustery Southern demagogue patterned after the assassinated Depression-era populist Huey P. Long, to perceptions of gaps in the narrative.

“It’s a bit of a surprise -- a surprise like getting hit by a truck,” Zaillian said. “I don’t know what to make of it.”

Zaillian said he hasn’t read many of the reviews, but it’s impossible to ignore the box-office numbers. “All the King’s Men” premiered in seventh place on the Sept. 22-24 weekend list of top-grossing movies, dwarfed by “Jackass: Number Two.”

“All the King’s Men,” which clearly had Oscar ambitions, had been scheduled for release last fall but was pushed back for rescoring and more editing, a decision that seemed to have changed positive expectations into questions about whether the movie was in trouble. Yet that kind of speculation doesn’t tend to affect broad consumer patterns, and Zaillian professed confusion over why so few viewers turned out.

“Maybe down the road I’ll figure it out,” he said. “We’re all a bit shellshocked. I feel like Huey Long must have felt -- you try to do good and they shoot you for it.”

The movie is based on Warren’s classic novel, which was inspired by the political rise and assassination of Long, a former governor and U.S. senator with presidential ambitions who took from his native state of Louisiana as freely as he gave. Penn is cast as corrupt Gov. Willie Stark; Law as Jack Burden, a political journalist turned fixer whose own amorality echoes Stark’s; and Winslet as Anne Stanton, whose relationships with both men are key to Stark’s fall.

Zaillian described the project as an “aberration in the studio system,” which he said tends not to invest in expensive adult dramas -- a decision reinforced by the opening weekend’s audiences.

“It’s dangerous for a studio to do financially,” Zaillian said. “The reason to do it from the studio’s standpoint is a good one -- because they believe in it in terms of the story.”

The academy has believed in the story too, though whether it will again seems a longshot. A 1949 adaptation by Robert Rossen won three Oscars, including best picture, a best actor for Broderick Crawford’s breakout portrayal of Stark and best supporting actress for newcomer Mercedes McCambridge as Stark’s mistress and political operative, Sadie Burke.

But that was a different time. With Long’s 1935 assassination still within memory and the world trying to shake off the horrors wreaked by more extreme demagoguery in Europe, Warren’s novel -- and Rossen’s film -- were seen as a warning about home-grown fascism.

In an interview before the movie was released, Zaillian said he believed Warren’s themes of morality and appeasement, the risks of demagoguery and the manipulation of the weak and vulnerable by the powerful, still had resonance today.

Yet Zaillian opted to set Warren’s 1930s story in the 1950s. The prewar years seemed archaic on film, he said, and the details of Warren’s story -- including old barnstorming political campaigning -- would have conflicted with contemporary political campaigns waged mostly through television advertising.

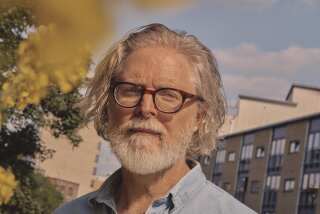

“In one form or another, it could take place at any time from the Roman Empire on,” said Zaillian, 53, who had not read the book until approached to take on the project. “It’s a great book to read for the first time. It’s so beautifully written. That’s the thing you worry about with great books. The poetry in them is part of their power, and in film you have to transfer a lot of those words and energy. A lot of great books don’t translate that well.”

Although Zaillian truncated portions of the novel, he stuck close to its core elements -- no small feat given Warren’s complex plotlines and flashbacks.

“It never occurred to me to change it in some major way,” Zaillian said. “The ideas in it, like getting your ends and means mixed up, a man of action versus a man of inaction ... those kinds of ideas are timeless.”

But judging by its 10-day gross of $6.3 million, the story seems less appealing to moviegoers than to readers -- the book is still in print and is required reading in many high school and college American literature classes.

Warren framed his novel on Long’s life and death but took the story in a wide range of directions. Narrated by the disillusioned Burden, who was raised in the genteel aristocracy, the novel traces Stark’s transition from ambitious hick to highly popular governor of a thinly veiled Louisiana. Stark’s quest is to improve the lives of his fellow citizens, in part by overturning a political structure that has bled the state dry. But in the end, Stark replaces a corrupt oligarchy with a corrupt dictatorship.

One of Warren’s obsessions in the book, reflected in both movies, is the dilemma that arises when moral people connive with the immoral to try to do good. Stark orders Burden to persuade his childhood friend, Adam Stanton -- Anne’s brother, a noted surgeon and son of a revered former governor -- to run a new state hospital Stark is building. Stanton, who despises Stark’s political machinations and blatant thievery, has his reservations, but he’s drawn in by the chance to do good.

Stanton promises himself and Stark that he’ll quit the first time Stark interferes with the hospital’s operations. But other pressures lead Stanton (played by Mark Ruffalo) to commit an overtly immoral act. Zaillian reduced that core element into a scene in which Stark and Stanton talk at the hospital construction site about moral relativity.

“That is what the story is all about, and I think he [Adam] is the perfect character for that idea,” Zaillian said. “Somebody who lives a moral life is capable of doing an immoral act, whereas people might look at Willie as an immoral character who does good things. There’s a great line about a man who writes a sonnet and everybody thinks it’s beautiful. Is it less beautiful if you find out he wrote it about somebody else’s wife? No, it’s still beautiful.”

One of the enduring elements of Stark’s character is that he is a man of naked ambition and a desire to do good, but whose hubris propels him to crash through ethical barriers. Once in motion, he is a car without brakes, learning the road from the thieves who traveled before him but accelerating ever faster. Complex and suspicious, he believes he has figured the game out, and thus can’t help but win.

Yet Stark remains a sympathetic character, even though he routinely betrays his wife and a series of lovers, old friends and cronies, and even his rivals. He leaves in his wake the disillusioned and the damaged -- yet another cost of embracing any means to an end.

Warren “never saw him as a complete villain, but as a complicated, real person,” Zaillian said. “There’s a side of Huey, and Willie, that’s someone who gets things done. That’s the dilemma. Does it matter how he gets them done?”

Given the current political climate, one would think -- as does Zaillian -- that Warren’s core exploration of means and ends would resonate today. But apparently not as much as Johnny Knoxville’s “Jackass” antics.

*

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.