This pirate historian tells dead men’s tales

- Share via

PORTLAND, Maine -- Long John Silver of “Treasure Island” fame, hobbling along on a peg leg with a talking parrot on his shoulder, set the mold for Hollywood’s image of a pirate.

Then came Captain Hook, thirsting for revenge against Peter Pan for cutting off his right hand and forcing him to wear an iron hook. Jack Sparrow, portrayed by Johnny Depp in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies, updated the image of the swashbuckling pirate with special effects and the supernatural, and his rum-soaked, dreadlocked portrayal.

But those looking to examine the true-life figures of the Golden Age of Piracy might turn instead to the likes of Samuel Bellamy, Charles Vane and Edward Thatch, sometimes known as Edward Teach but known best as Blackbeard.

The exploits of those three pirate leaders, along with Woodes Rogers, the ex-privateer who hunted them down, are detailed in Colin Woodard’s “The Republic of Pirates,” a history of the rough-and-tumble period from 1715 to 1725 when buccaneers ruled the seas, disrupting trans-Atlantic commerce.

Operating from sanctuaries in the Bahamas and the Carolinas, pirate crews were largely comprised of ex-sailors in revolt against tyrannical conditions on merchant and naval ships. They struck at will at British, French and Spanish vessels from New England to South America and captured treasure, along with the imagination of the public.

“Pirates were folk heroes at the time they were alive. Large numbers of ordinary people looked upon them as heroes and bought their arguments that they were Robin Hood’s men,” Woodard says.

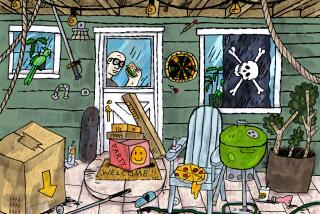

Today they’re as popular as ever, thanks in large part to the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies, the first of which hit the big screen in 2003. The white-on-black Jolly Roger, meanwhile, has gone mainstream, with even professional sports teams picking up on the theme: the Pittsburgh Pirates, Oakland Raiders and Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

“You see the skull and crossbones everywhere -- on flags, on T-shirts and on bumper stickers,” Woodard said. “What people are responding to is the fantasy image of the pirates.”

While researching, Woodard found that many of the classic images from pirate tales don’t ring true. He found no evidence, for example, that pirate captains ever dispatched captives by making them walk the plank. Likewise, he’s skeptical that pirates made a habit of digging a hole and burying their treasure.

And so far as Woodard knows, the trademark “arrrgh” was first uttered by actor Robert Newton in his 1952 portrayal of “Blackbeard the Pirate.”

But some celluloid pirate images, such as Jack Sparrow’s flamboyant mode of dress with his dark kohl-rimmed eyes, may not be off the mark.

“One of the things they liked to do when they captured a vessel was immediately raid the wardrobes of the wealthy passengers and wear the stuff like war trophies,” Woodard says. “They had a flair for finery.”

The wooden legs and eye patches that are typical of pirate movies may have had a basis in fact, he said, as cannon blasts and hand-to-hand battles between merchant crews and boarding parties took their toll.

“It was a dangerous occupation,” he notes.

Pirates also consumed prodigious amounts of rum, wine and whiskey, Woodard said. His book details numerous incidents in which pirate crews would attack a ship when their stocks of booze had run perilously low.

“They preferred to live a merry life and a short one,” Woodard says. “They knew that what they were doing was such that their chances of living to a ripe old age were small.”

A native of Maine, Woodard has combined his work as a historian with his assignments as a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor and the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Although some pirates could be cruel, the author offers a generally sympathetic portrait of a subculture that often practiced a rough democracy, treated its captives in a civil manner and displayed racial tolerance.

Such attitudes, according to the author, reflected the kind of independent thinking that two and three generations later was emblematic of the American and French revolutions.

“A lot of that mob revolutionary sentiment and inclination toward roughshod, radical democracy and resisting the forces of empire was already prevalent earlier than anyone suspected,” Woodard says.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.