JOEL AND ETHAN COEN: MAKING A LITERARY MONSTER REAL

- Share via

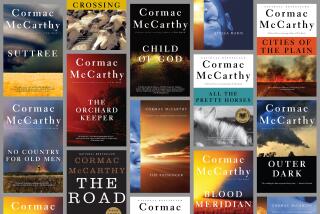

PERHAPS the most indelible character in Cormac McCarthy’s novel “No Country for Old Men” is the unstoppable killer, Anton Chigurh. In the hands of Joel and Ethan Coen, he also becomes one of the screen’s great monsters -- not only through Javier Bardem’s chilling performance, but also through canny cinematic decisions.

“In the novel, he’s ultimately a mysterious character,” says Ethan Coen, who teamed with his brother to write, direct and edit the film. “You can’t say anything about him you couldn’t truthfully contradict by saying the opposite.”

“He seems to be superhuman but he bleeds,” says Joel. “There’s a way that, even in the novel, you’re allowed to feel the character has another kind of agency and may be somewhat symbolic or metaphorical.”

Throughout both versions, the very real, very solid Chigurh makes an impression on a number of people, few of whom live to ponder the experience. But in the film, which earned eight nominations, the first time he crosses paths with the man he relentlessly hunts, Llewelyn Moss, he seems as ephemeral as an evil spirit. The ensuing nocturnal shootout is executed with taut economy.

“That’s one of the few places where we’re not at all faithful to the book,” says Ethan. “The corresponding action scene in the book is very different: It involves characters from the Mexican side of this transaction gone wrong; it becomes very shoot-’em-up, very noisy. We changed it to limit it to those two characters.”

McCarthy’s original scene actually brings the two principals face to face, with Moss getting the drop on Chigurh:

Moss picked up the man’s shotgun and threw it onto the bed. He switched on the overhead light and shut the door. Look over here, he said.

The man turned his head and gazed at Moss. Blue eyes. Serene. Dark hair. Something about him faintly exotic. Beyond Moss’ experience.

This is closer an encounter than any the two have in the film, part of the Coen brothers’ scheme to deepen the killer’s almost supernatural inscrutability. On screen, the quarry never has more than a suggestion of Chigurh; the evidence of his presence is in muzzle flashes, a shadow beneath a door, a ghostly reflection in a shop window.

“Part of the environment,” says Ethan. “That is drawn from the book, the ambiguity about that character being supernatural or ghostlike in some way, and yet just when you feel you’ve pegged him like that, he acts in a very human way.

“It’s kind of what was interesting and unsettling about that character in the book, and part of what animated that scene when we were thinking about how to do it.”

--

-- Michael Ordona

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.