50 years after he broke color line, hockey returns the love to O’Ree

- Share via

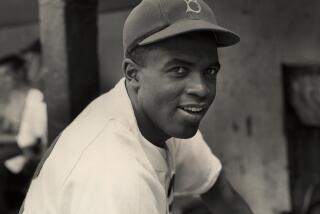

Friday will mark 50 years to the day that a rangy black kid from Fredericton, New Brunswick, donned a Boston Bruins sweater and broke pro hockey’s color barrier on a sheet of ice in Montreal.

If you’re lucky enough to catch 72-year-old Willie O’Ree telling stories during the festivities the NHL and the rest of the hockey community has planned to commemorate the occasion, listen closely. Turns out he’s got another tale about overcoming adversity that might be even better.

“That’s one reason I feel blessed, “ O’Ree said in a telephone interview from Boston, where he was to be honored before a game weekend game against the Rangers. “I work with kids through my role with NHL Diversity and it’s a chance to tell them, ‘If you really feel strongly enough about something, you’ll find a way to make it happen.’

“I guess that’s why I’d like to be remembered most for what I’m doing now,” he added a moment later, “for giving back to the sport for everything it gave me.”

The reason O’Ree loved hockey more than it loved him -- at least until recently -- is because he made a comfortable, joy-filled living playing left wing for 21 years, nearly all of it in the minor leagues, while almost nobody knew he was blind in his right eye.

O’Ree was hit by a deflected shot playing in an Ontario junior league game some two years before his historic pro debut. When he came to after an operation, the first few words he heard couldn’t have been more devastating.

“The surgeon said my sight was gone and that I’d never play hockey again,” O’Ree said. “I was 19, going on 20. Everything I loved from the time I was a kid was about to disappear.”

A month later, though, O’Ree laced on a pair of skates, determined to regain mastery over the things he could control and not worry about the rest.

“Back then,” he chuckled, “nobody gave players eye exams. They might look at your knees, or how bruised the rest of you was, but that was it. Desire will take you a long way.”

After patiently climbing the minor-league ladder, O’Ree got called up to Boston and ushered into Bruins general manager Lynn Patrick’s office along with coach Milt Schmidt. The conversation was brief and to the point.

“They said, ‘We know you can play,’” O’Ree recalled. “‘Don’t let anything you hear shake that belief.’”

History suggests even that brief conversation was unnecessary. It was a decade after Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, O’Ree had already played in Montreal as a minor leaguer without incident, and teammates, fans and even opponents treated him respectfully. His pioneering role in that Jan. 18, 1958 game seemed so unremarkable at the time that it didn’t merit mention in most newspaper accounts the next day.

He stayed with the club for the return home game in Boston, then went back to the minors, not returning to Boston again until 1961. In all, O’Ree wound up playing only 45 games in the NHL. But that’s when his story got even more interesting.

The pay wasn’t as good and the fans weren’t as tolerant at some of the minor-league stops. Playing in the old American Hockey League, O’Ree found himself in a few Southern towns where racism still wasn’t muted. At least he knew what to expect, having spent a few weeks in Waycross, Ga., in 1956, trying out for baseball’s Milwaukee Braves. His favorite story from that experience was the bus ride back.

“I got cut, but I wouldn’t have taken the job even if they’d offered me one. Whites-only this, coloreds-only that -- I couldn’t live that way,” he said. “When I got on the bus out, I went right to the back and didn’t get off, except to use the bathroom or grab a sandwich.

“But the farther north we went, the more I moved up. And by the time we got to the [Canadian] border,” O’Ree said, “I was in the front seat.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.