Beijing simmering over ‘the Egg’

- Share via

BEIJING — It’s the building Beijing residents love to hate.

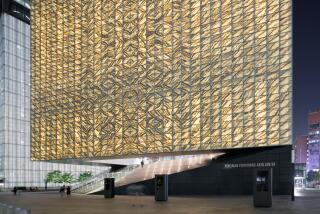

The dome of the new National Center for the Performing Arts glows luminescent as it emerges from a reflecting pool like a pearl or a rising sun. At least that’s the impression the French architects of Beijing’s arts center wanted to create.

The $360-million complex, an extravaganza of titanium and glass bigger than New York’s Lincoln Center or Washington’s Kennedy Center, is supposed to shout out to the world that Beijing has arrived, both as an economic and cultural capital. But to many here, the center resembles nothing grander than an egg plunked into a pot of boiling water.

In fact, since it opened in December, the building has already acquired the nickname of “the egg.”

“Egg” is not a flattering epithet in Chinese, being attached to various insults such as ben dan (stupid egg) and huai dan (rotten egg). (There is no “good egg” in Chinese slang.)

“Personally, I do not like the nickname ‘the egg,’ but everybody has a right to express his opinion,” Deng Yijiang, vice president of the center, said during a recent Chinese New Year reception.

French architect Paul Andreu’s design was selected in 1998 by the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, which decreed it would “contribute to the development of Chinese spiritual civilization, advanced social culture and harmonious society,” according to an exhibit in the center’s lobby.

Among the rejected proposals was a building resembling a clock radio and one that looked like a giant Snickers bar.

The positioning of the ellipsoidal dome in the middle of the pool is meant as a tribute to the ancient Chinese concept of round sky and square earth. But many traditionalists find the modernistic design a disruption to the feng shui, or harmony, of Beijing and therefore the nation.

The capital of the Middle Kingdom is laid out in a series of concentric circles around the Forbidden City, the former residence of the emperors, and the arts center is adjacent to the sacred inner circle. The site is just to the west of Tiananmen Square’s Great Hall of the People and so close to the country’s most famous portrait of Mao Tse-tung that some say the founder of communist China is raising an eyebrow in astonishment at the outrageous architecture.

“It looks like a quasi-foreign devil in the historic palace area,” sneered a 52-year-old blogger who goes by the name Lao Youer. “If you weren’t told it was the national theater, you would probably think it was an oil tank or a huge warehouse.”

Twenty-first century Beijing has become a showcase for some of the world’s most audacious buildings. Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas’ $600-million headquarters for Chinese Central Television struts across the Beijing skyline on two legs like a giant robot, so big that it resembles a modern-day Colossus of Rhodes. (“Like a pair of trousers. Imagine how awful it would be to work in the crotch,” a 25-year-old insurance auditor wrote on a popular blog.)

The 100,000-seat Olympic stadium designed by the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron has been dubbed the “bird’s nest” for its elaborate webbing of steel beams.

Striking to be sure, but critics complain that these new buildings are like the preposterous outfits fashion models flaunt on the runways: interesting to look at, but you wouldn’t be caught wearing one in real life.

“These European architects are doing things in China they wouldn’t dare do at home. They’re using China as their testing grounds,” said Peng Peigen, an architecture professor at Qinghua University in Beijing.

One of the most outspoken critics of the new edifices, Peng was the author of a 2004 letter that academics sent to Premier Wen Jiabao protesting the building awards to foreign architects.

Peng’s objections have less to do with aesthetics than with cost and safety. The new Olympic stadium, Peng insists, uses as much steel as four stadiums. The design of the national arts center in the center of a pool means the entrances and exits are underground, making it difficult to evacuate the building in an emergency.

“You would have to run 250 meters [820 feet] from your seat to get out in a fire,” Peng said. “That would never be allowed under the building codes anywhere in the United States or Canada.”

A coincidence that gave credence to the critics was the collapse in May 2004 of a terminal designed by the same architect at Charles de Gaulle International Airport in Paris. Four people were killed.

The arts center is not really a single building but a cluster of three theaters -- an opera house, concert hall and traditional Chinese theater -- under the vast dome. Entry is via a long staircase under the reflecting pool.

The box office, main lobby and an exhibition about the architecture are in this basement level. A long corridor leads to the center of the complex, a large atrium encased by the dome.

It is here that the interior is most impressive.

Slender escalators that look like they’re suspended in the air crisscross the atrium, climbing to balconies that lead to the upper levels of the theaters. The vast ceiling under the dome is lined with slats of Brazilian redwood. The effect is something between a 21st century airport and the innards of a piano.

The site was designated in the 1950s for an arts center that was to be built with Soviet help, but the project was delayed by chilling relations between the countries, and it was shelved entirely during the Cultural Revolution.

“I’ve waited for 50 years for China to get its own performing arts center,” said Yang Hongnian, who was conducting a Chinese choir last month at the concert hall.

Yang, whose shaggy silver hair brings to mind the late Leonard Bernstein, recalled traveling to Italy as a young man and envying the opera houses and concert halls he thought China would never have. “This was only our dream.”

The lavishness of the new center shows the extent to which China’s current leadership has embraced Western culture, or at least high culture -- as though its guiding motto was, “If you build it, they will come.”

Indeed, during its first six weeks in operation, the center was play host to soprano Kiri Te Kanawa, tenor Jose Carreras, conductors Kurt Masur and Seiji Ozawa, and the Kirov Ballet. By providing a venue, China hopes its performers will rise to world-class standards in the Western performing arts.

Of course, Western culture doesn’t come cheap. Ticket prices for international performers are about the same as anywhere in the West. In a country where many people are resentful of the growing gap between rich and poor, the arts center is one more source of umbrage.

“The tickets are too expensive. My family would never get a chance normally to see this place,” said Zeng Huan, a 16-year-old student who was lucky enough to visit with her high school class.

During the Chinese New Year, hundreds of tourists from the Chinese countryside milled around the entrance but were unable to get past the box office in the outer lobby. A spokeswoman for the center said tours of the building would soon be available, at a lower price.

--

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.