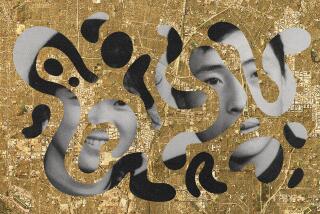

Chinese city welcomes Japanese back

- Share via

DALIAN, CHINA — Looking back, Japanese businessman Tomatsu Ito says, he might as well have moved to Mars rather than a few hours’ flight away to China.

Unlike in his publicly polite homeland, drivers in Dalian were chaotic, often careening through crowded crosswalks. Worse, he couldn’t muster even the most basic Chinese.

Often desperate, he would phone JianHua Yang, his second in charge at the branch office of an Osaka, Japan-based software company. Yang is a Dalian native who, like many here, speaks Japanese.

“I’d call him out of nowhere,” Ito recalled. “I’d say, ‘I’m lost again. I have no idea how to get home.’ ”

Their budding bicultural friendship symbolizes a trend here: Ito is among thousands of Japanese flocking to this bustling port on China’s eastern seaboard. Resentment still runs deep in China over Japan’s 40 years of often brutal colonial rule in this region in the early 1900s, but Dalian has become a singularly welcoming oasis.

Seeking to establish a regional high-tech hub, Dalian officials are courting Japanese investors, offering tax breaks and talking up the city’s weather, infrastructure, friendliness and proximity to Japan.

Dalian, a Japanese military hub in the colonial years that still bears the stamp of the past, features direct flights to Japan and hotels catering to the Japanese. Many road signs are in Chinese and Japanese.

At a business zone called the Dalian Software Park, Japanese firms make up a quarter of the 450 tenants. Local universities are crowded with thousands of young Chinese studying Japanese, many of them seeking software careers. Others staff new business call centers where multilingual Chinese workers serve the needs of customers in Tokyo and other cities across Japan.

When Ito drives on roads with names like Japanese First Street and Japanese Fragrance Street, he said, Dalian feels like a second home.

“The troubled history between Japan and China is not that remote, but it is in the past,” the 52-year-old said. “The new generation seems to have put this behind them. They want to move on.”

Yet Dalian remains conflicted. Although Japanese business provides jobs and development capital, many of Dalian’s 6 million residents still carry the scars of a war with Japan’s Imperial Army.

Under an urban renewal program, Dalian recently began demolishing hundreds of decaying colonial-era villas that housed Japanese upper-class families and commissioned officers. Over the protests of historians, a third of the 600 structures have been destroyed, with piles of brick and jagged mortar lining both sides of Harbin Street in the Nanshan neighborhood.

“Scholars can say, let’s keep these structures, but nobody else would dare advocate for this,” said Lu Wei, a professor of construction at Dalian University of Technology. “Those homes built during Japanese occupation -- for average people, it’s unsafe to say we should keep them. Your neighbors can accuse you of being overly pro-Japanese.”

Sitting on the stoop of her Nanshan apartment building, Li Pingwei said the Japanese revival has been good for her family’s jade business. She has even learned to speak the language. But she remains bitter.

“The Japanese were so cruel to the Chinese,” she said. “They may be creating jobs in Dalian, but I will hate them forever.”

Some of Dalian’s young people agree, preferring to weather a less lucrative Chinese-speaking job market than learn Japanese.

“They refuse to study the language because of what the Japanese military did to our forefathers,” said Li Zhaogang, a professor at Dalian University of Foreign Language’s school of software. “They still harbor this national hatred.

“We say to the Japanese, ‘Come and do business, but don’t expect us to forget.’ ”

A century ago, two foreign empires battled over control of Dalian, which was prized for its ice-free deep-water port.

In Russia, the city was known as Dalny and Czar Nicholas II sought to duplicate the success of Vladivostok, a major Russian port on the Pacific. But after years of war, the Japanese army eventually prevailed in 1905 and the city was renamed Dairen.

For four decades, Japanese engineers rebuilt the seaside gem, which on many maps of the era was shown as part of imperial Japan, with a population of 300,000 Japanese.

Modeling the city after their homeland, for example, they built the Dalian train station, still considered among China’s best, as a replica of Ueno Station in Tokyo.

Between 1931 and 1945, when the Japanese army was accused of conducting civilian executions elsewhere in China, most notably in the city of Nanjing, Dalian was spared.

“The Japanese have always been rather paternal toward Dalian,” said Gao Wei, general manager of the Dalian Software Park. “There aren’t the tensions here that there are in the rest of China.”

Tokyo native Mami Imamura, who opened Dalian’s first Japanese-owned beauty salon seven years ago, learned of the abuses only after she arrived in China.

“I feel really sad about what the Japanese did here,” she said. “But there is nothing I can do about the past.”

She feels the weight of Dalian’s historical anger.

Men who come to her shop refer to her as that “little Japanese” and taxi drivers have repeatedly uttered offensive Japanese phrases memorized from old war movies.

“I’ve felt harassed,” she said. “But Chinese friends have explained to me that the men often don’t even understand the words they are saying.”

For his part, Ito says that although many of his countrymen here celebrate the city’s lack of Japanese formality, China’s anything-goes culture can create problems.

Some business call centers have cut back on hiring Japanese-speaking Chinese because some had offended customers in Japan by failing to use proper honorifics. Now, they’re bringing in young native speakers from Japan.

“In the Japanese workplace, rules are strictly followed . . . ,” Ito said. “Many people don’t understand Japanese culture. But they’re learning.”

Ito has learned a few lessons himself: Thanks to Yang, 42, he said, he felt more Chinese every day, starting with the small things.

He used to pay five times as much for bananas because he was Japanese. “Now, I get the local price,” he said.

--

Eliot Gao in The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.