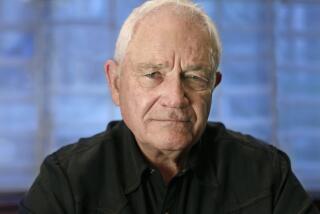

Director Tom Hooper on ‘The King’s Speech’

- Share via

At first blush, “The King’s Speech” sounds like an awards-season special: Take one well-respected but under-recognized actor, add a historical personage with a debilitating physical condition and wham — instant Oscar. But Tom Hooper, who directed HBO’s miniseries on the life of John Adams, doesn’t put historical figures under glass or drown them in a sea of prestige gloss. Colin Firth’s performance as the future King George VI, who overcame a profound stutter with the help of an Australian speech therapist played by Geoffrey Rush, is regal and very human; it’s not showy, revealing itself in intimate details rather than broad strokes. Credit for that goes to Firth but also to Hooper, who shot close-ups with the camera only inches from his actors’ faces, giving them no room for pretense

Although it began as a screenplay, you first came across “The King’s Speech” as a play script. What made you think it would work better on film?

I felt the language of the close-up is needed for stammering, because you see what’s going on in the eyes. I’d seen footage of the real king, in wide shot and in close-up, and it was only in this bit of archive that I found the longing to do it right and the pain of drowning in these long silences.

How do you balance approaching members of the royal family as people with conveying a sense of their symbolic weight?

The thing about having a stammer is it really does humanize the king, and I think the real King George VI was hugely humanized in the eyes of the people by his struggle with his stammer. People knew. They didn’t know about the speech therapist but they knew he was coping with a stammer. It made people connect with him in a strong way.

In retrospect, it’s obvious that Colin Firth was right for the part, but how did you decide on him?

King George VI, in my research, is nice to his core, humble to his core, and I think Colin is nice to his core. I now know him very well and there doesn’t appear to be a malign bone in his body. He always had an incredible gentleness and humility as a person — and it’s not an act. So I thought spiritually there was an incredibly strong connection between the two people. Where there’s not a strong connection is that Colin is perhaps the most enthusiastic anecdote-teller I’ve ever worked with. In rehearsal, I had to impose a strict two-minute anecdote rule on him, and by the shoot it had to come down to a 30-second rule, otherwise we’d never have got anything done. The irony did not escape me that the best raconteur I know was playing a man who could not speak.

Much of the film is composed of two men in a room. How did you make that visually compelling?

I was very interested in trying to find a visual analogue to the stammering experience. I felt the stammering was about inhabiting these painful silences, silence and absence. And therefore I was interested in framing Colin’s face in relation to negative space in the image. I would set Colin against these big empty walls to suggest the emptiness of what he was struggling against. Sometimes there are shots where he’s in the corner and the wall is overpowering him and there’s little headroom in the frame. I shot the close-ups on fairly wide lenses, which means it’s very intimate.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.