We should have kept Davis

- Share via

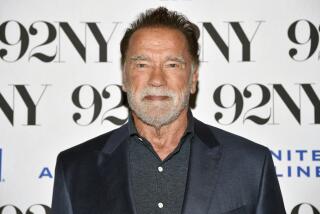

SACRAMENTO — One thing should now be evident as Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger packs up his office: It was a mistake to recall Gray Davis.

Davis didn’t deserve it. He had just been reelected the year before. He would have been out of office in three years anyway.

Schwarzenegger wasn’t an improvement except for, briefly, providing entertainment. He didn’t make the state’s money mess any better. In fact, it has gotten worse.

It was not a citizen uprising that dumped Davis, a Democrat. The 2003 recall election was called because one ambitious Republican congressman, Darrell Issa of Vista, spent $1.7 million of his own money to collect the needed signatures.

Issa wanted to run for governor himself. But he gave it up when Schwarzenegger leaped into the race. And the “action hero” movie star entered only after popular U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-San Francisco) made it clear she wasn’t going to run. The notion of recalling a sitting governor repulsed her.

So there was a lot of drama -- followed by years of disappointment.

The celebrity governor had his accomplishments: a workers’ compensation overhaul for business (started by Davis), political reforms (independent redistricting, open primary), $37 billion in public works bonds, the nation’s first anti-global warming legislation, the first major waterworks package in decades, state pension rollbacks and a “rainy day” budget reserve (pending future voter approval).

The centrist Republican claims more credit than he deserves for some of those things. Legislators and reformers also gave big shoves. But I won’t quibble here.

Schwarzenegger failed to achieve education reform -- Davis did take a big step there -- or restructure the state’s outdated tax system. Neither did he exactly “sweep the special interests out of the Capitol,” as promised.

But his most glaring and critical failure was to not “tear up the credit cards,” “end the crazy deficit spending” and “live within our means” as he repeatedly vowed.

Maybe no governor could have. The worst recession since the 1930s ravished state treasuries all over the country. But Schwarzenegger, dealing with the Legislature, could have come closer to balancing the books than leaving a $28-billion deficit projected for the next 18 months.

Of course, California’s governing system is geared for gridlock.

“We’re all part of a system basically designed not to work,” says Democratic state Treasurer Bill Lockyer, Sacramento’s most experienced politician, who received more votes in November than any other candidate for any office.

“That’s why we have three branches and two [legislative] houses. They’re meant to have government not do much and theoretically leave people alone. In California, we’ve added lots of complications: The two-thirds [majority] vote, term limits, the initiative.

“We’ve complicated the system while people’s expectations about what government should do have grown exponentially.”

Expectations have grown partly because politicians have over-promised. And Schwarzenegger is a prime example of a promisor who couldn’t produce. That’s one reason his popularity plummeted.

Another is that his shtick got old early -- all that showmanship, the bravado, the alternating “fantastic” happy talk with the “girlie men” rant.

But Lockyer touches on a bigger problem that hurt Schwarzenegger in trying to govern.

He didn’t seem to understand the concept of checks and balances, the American system of democracy. It took too long for him to realize -- if he ever did -- that a governor cannot always force his will on a Legislature or be a pied piper to the people.

Maybe it was because Schwarzenegger grew up in Austria and didn’t take American civics.

Probably it was because as an adored international superstar, he mostly had his own way. If he figured two plus two equaled five, others agreed. No need to hear other views. No reason to compromise.

“He came out of two professions where it was mostly about individual effort -- body building and the movies,” says longtime Republican strategist Ken Khachigian. “Your own personal effort and your personality got you through.

“Being governor, you can’t just use your personal strength or force of personality to get things done by yourself. Schwarzenegger grew up in a different culture.”

Then again, it was career politician Davis who ran for governor offering “experience money can’t buy” and later infamously said of legislators: “Their job is to implement my vision.”

Schwarzenegger also had another problem, one he couldn’t do much about: English was his second language. He once told aides that he actually did budget math in German.

Lacking good command of English, Schwarzenegger sometimes had trouble communicating. Spokesmen would urge reporters to write what he meant, not what he said.

One example: When he spoke to newspaper editors and advocated “closing” the Mexican border. He really meant “securing.” Huge difference.

More important, he often labored to explain complicated issues and sell his solutions to legislators and voters. He seemed to dumb down the subject.

Schwarzenegger was delusional about the politically possible. He prided himself in “thinking big,” being “bold.”

Big changes are needed. But voters today are suspicious of big and mistrustful of politicians, as Schwarzenegger learned in two special elections. This is a period for cautious incrementalism.

Davis was risk-averse. He also had other faults. But Schwarzenegger had as many.

We’d have been better off -- Schwarzenegger included -- if Davis had been permitted to finish his term. That would have allowed the action hero time to bone up on the democratic process before running and probably winning in 2006.

--

george.skelton@latimes.com

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.