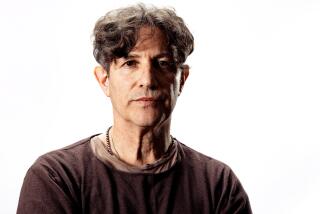

‘Reality Therapy’ psychiatrist

- Share via

Dr. William Glasser, a psychiatrist, education reform advocate and best-selling author whose unorthodox emphasis on personal responsibility for mental problems sold millions of books, caught the attention of educators and earned him an international following, died Friday at his Los Angeles home. He was 88.

He had pneumonia that led to respiratory failure, his son, Martin Glasser, said.

Glasser was not a typical psychiatrist. He did not prescribe psychiatric drugs to patients, did not dwell on their past behaviors or subconscious thoughts, and largely ignored the standard diagnoses of mental disorders adopted by his profession. At the risk of sounding like a simpleton, which fit some critics’ views of him, he often said there was only one problem that sent people into therapy. “They are unhappy,” he said.

In his 1965 book “Reality Therapy,” he said unhappiness usually stems from a person’s inability to fulfill two basic needs: “the need to love and be loved, and the need to feel that we are worthwhile to ourselves and to others.” Glasser counseled patients to take responsibility for fulfilling those needs in a positive manner and believed even schizophrenics and manic depressives could benefit from his approach.

“Reality Therapy” sold about 1.5 million copies, according to HarperCollins executive editor Hugh Van Dusen, and provided an intellectual basis for the school reform program he described in his next book, “Schools Without Failure” (1969).

In that book Glasser called for building emotional ties between students and educators, making lessons relevant, and abolishing grades below A and B with an overall goal of helping students attain competence.

There are 17 schools in the United States and three in Australia, Ireland and Slovenia that have declared themselves Glasser Quality Schools with faculties trained by instructors from the William Glasser Institute based in Country Club Hills, Ill.

The extent of Glasser’s influence in education is difficult to gauge, but in 1971 The Times reported that 600 schools and 8,900 teachers were using some of his ideas.

“A lot of schools are using the ideas without going through the official training,” said Kay Mentley, who heads the 1,300-student, Glasser-inspired public charter school Grand Traverse Academy in Michigan. She credits the school’s high academic achievement, trusting relationships and lack of discipline problems to Glasser’s philosophy.

His progressive approach drew the ire of traditionalists, such as Charles J. Sykes, author of “Dumbing Down Our Kids: Why America’s Children Feel Good About Themselves But Can’t Read, Write or Add” (1995). Glasser’s “Schools Without Failure,” Sykes wrote, was “a veritable handbook for schools that would fail over the next two-and-a-half decades.”

Glasser’s interest in psychology stemmed from an eagerness to deal with his own intensely shy nature. The son of a watch and clock repairman, he was born in Cleveland on May 11, 1925, and earned a degree in chemical engineering in 1945 from what is now Case Western Reserve University.

After a brief, unhappy stint as an engineer, he returned to the university to study psychology. At the urging of a dean, he applied to medical school to become a psychiatrist and earned a medical degree from Case Western in 1953.

He completed his medical residency under UCLA supervision at the Veterans Administration hospital in West Los Angeles, where he irritated his superiors with his anti-Freudian tendencies.

“What they taught, in effect, was that you aren’t responsible for your miserable problems because you are the victim of factors and circumstances beyond your control,” Glasser told The Times in 1984. “I objected to that.... My thrust was that patients have to be worked with as if they have choices to make. My question is always, ‘What are you going to do about your life, beginning today?’ ”

At the end of his residency, he said, “I was thrown off the staff.”

His approach was welcomed at his next job as staff psychiatrist at the Ventura School for Girls, a reform school in Ventura, where he taught troubled girls to take charge of their own behavior. Many of the case histories were in “Reality Therapy.”

“He would hold them responsible for their behavior, not accept the fact that they could get away with blaming their past or society,” said Bob Wubbolding, a licensed psychologist in Cincinnati who was Glasser’s director of training for 23 years. “A lot of psychologists functioned on that basis but it wasn’t emphasized then, it wasn’t part of their formal training. That is his major contribution.”

Today most textbooks in graduate counseling programs include chapters on reality therapy, which Glasser later called control theory or choice theory, Wubbolding said.

Glasser wrote more than 20 books, including “The Quality School: Managing Students without Coercion” (1990) and “Warning, Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health” (2003).

“His therapy was so effective that people got well quick, so he couldn’t make any money on it,” his wife, Carleen Glasser, said of his private practice. “So he started to write these books.”

She was his coauthor on three books, including “Getting Together and Staying Together: Solving the Mystery of Marriage” (2000). He also wrote several books with his first wife, Naomi Glasser, who died in 1992.

In addition to his wife and son, he is survived by five grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

--

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.