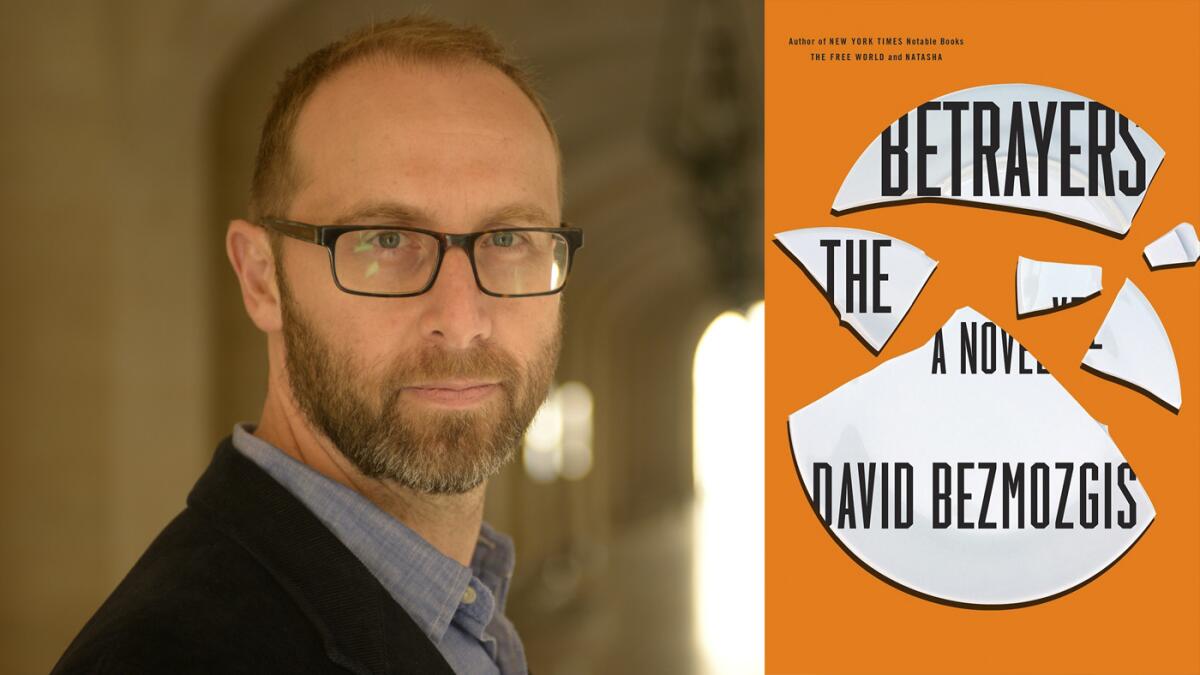

Review: Blame and forgiveness in David Bezmozgis’ ‘The Betrayers’

- Share via

What does the novelist do in the face of history? Such a question, notes David Bezmozgis in his essay “The Novel in Real Time,” once made Philip Roth worry about contemporary fiction, which he feared might be overwhelmed by “our absurd and almost unaccountable reality.”

Bezmozgis’ new novel “The Betrayers” is a case in point: the story of an Israeli politician who, on the losing side in a dispute over settlements, flees Tel Aviv with his young girlfriend for Yalta, in the Ukraine, where as a boy he spent a glorious summer with his parents.

In the real world, of course, Israel exploded in conflict in recent months, as did the Ukraine. On the one hand, this means “The Betrayers” couldn’t be more timely, but on the other, timeliness is not what fiction does. As Bezmozgis (a New Yorker “20 Under 40” writer who has written one previous novel, “The Free World,” as well as the collection “Natasha”) acknowledges, “I felt frustrated that world events conspired to undermine my design for the book.”

And yet, “The Betrayers” largely sidesteps such concerns by focusing not on politics but personality, beginning with that of its protagonist, Baruch Kotler, 60 years old, a hero of the Jewish state, who spent better than a decade in the Soviet gulag after having been betrayed by someone he thought of as a friend. The broad lines of his life resemble those of Natan Sharansky, the Russian-born refusenik who was an international cause célèbre in the 1970s.

Like Kotler, Sharansky became a high-ranking Israeli official; in 2005, he resigned his Cabinet position to protest the withdrawal from settlements in Gaza and the West Bank. What separates them, however, is that Kotler throws it all away by having an affair with his assistant Leora, an act of self-indulgence that opens up the issue of betrayal at the novel’s core.

Left behind are his long-suffering wife, Miriam, who lobbied for 13 years to free him from the Soviet Union, and his son Benzion, an Israeli soldier who cannot stomach the evictions he has been ordered to perform. “You, Mama, Benzion,” Kotler’s daughter Dafna declares late in the book: “all of you with your sacred principles. … And look at us. Look at all the good they have done us.” This is the novel’s central dichotomy, between public and private, between the demands of what we stand for and the more tenuous territory of what we feel.

Such a tension grows only more heightened after Kotler and Leora lose their hotel reservation in a mix-up and find a room with an older couple that rents to vacationers. By fate, or coincidence, half of this pair is Vladimir (now Chaim) Tankilevich, the very man who betrayed Kotler to the Soviet authorities.

For the last 40 years, as Kotler became an international figure of conscience, Tankilevich has been vilified, regarded as a Judas figure: Now, in his early 70s, he is resentful and suspicious of the world. Needless to say, this adds another layer to the novel’s consideration of betrayal and its aftermath.

Once Kotler realizes his landlord was his betrayer, he becomes intent on a reckoning; “I want to know,” he tells Leora. “… First and foremost. It is a need like hunger. You satisfy the need, and the rationale, the why, comes after, once you are sated.”

At the same time, Bezmozgis wants us to consider, can there really be a reckoning when, as Tankilevich insists, what he has given Kotler is a gift? “Say what you will,” he argues, “but you benefited from this Gulag. You had thirteen dark years followed by how many bright ones? Without those thirteen years, where would you be? You say living a normal life. Am I living a normal life?”

It’s a fascinating question, one that turns the dynamic of this novel in an unexpected direction. What does it mean if Tankilevich has been betrayed as much as Kotler? Only, perhaps, that the ultimate betrayals belong to history, which subjugates us all.

“[I]t is not even a matter of forgiveness,” Kotler tells Tankilevich’s wife, Svetlana. “I hold him blameless. I accept that he couldn’t have acted differently any more than I could have acted differently. This is the primary insight I have gleaned from life: The moral component is no different from the physical component — a man’s soul, a man’s conscience, is like the height or the shape of his nose.”

The point is that we do what we have to do, what we are wired to do, that free will is an illusion, that we are all pawns to history’s larger narrative. On some level, it’s a religious perspective, although Kotler, for all his Zionist fervor, is no longer exactly a believer; “This line of thinking,” he reflects, considering the complications of faith and politics, “had always existed and there was space for it. But, increasingly, it left less and less space for anything else.”

So why, I wonder, given the compelling issues it raises, does “The Betrayers” come off as flat to me, more a morality play than a slice of life? Partly, it’s the contrivance of the construct: “Of all the rented rooms in all the towns in all the world,” we can almost imagine Tankilevich lamenting, “he walks into mine.” This is no small matter, since the trick of fiction is that it has to be believable, which means it requires something of the elusive indirection, the chaotic open-endedness, of actuality.

Even more, there is the sense that even as they must once again confront each other, Kotler and Tankilevich are not so much people as archetypes, the saint and the sinner, brought together by the justice of the universe. That’s a lovely thought, but if events in Israel or the Ukraine have anything to tell us, it’s that justice is irrelevant when it comes to what happens in the world.

“The Betrayers,” then, reads less as a parable of reconciliation than an expression of its own inability as a novel to live up to the vagaries of history.

The Betrayers

A Novel

David Bezmozgis

|Little, Brown: 240 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.