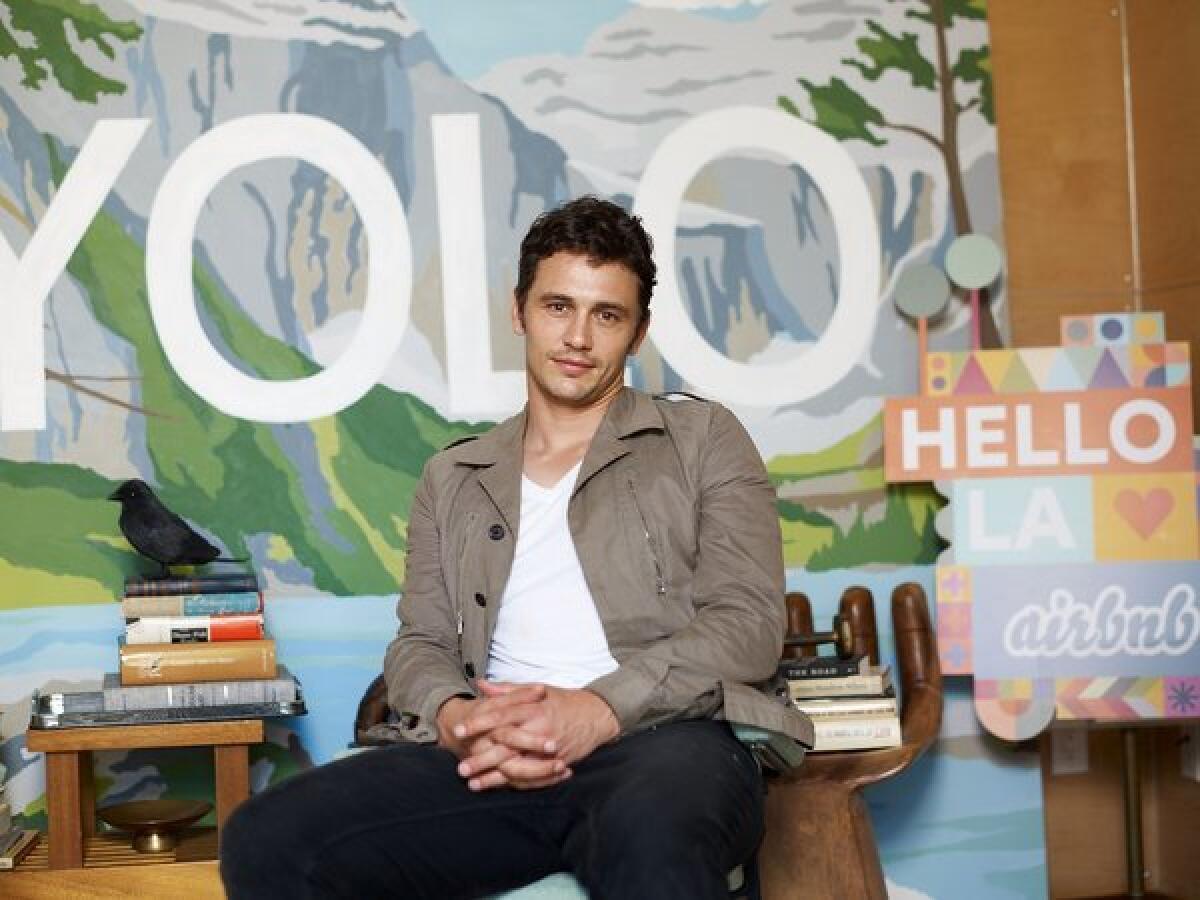

James Franco’s ‘Actors Anonymous’ says a lot about James Franco

- Share via

When will James Franco slow down? The prince of perpetual motion continues his blur of activity, starring in movies, writing screenplays, attending classes, unveiling solo art exhibits, posing for Gucci ads and engaging in attention-seeking Instagram stunts. Whether he’s pandering for press or punking all of us, one thing is clear: James Franco is going to do whatever James Franco wants whenever James Franco wants it.

This lack of self-restraint echoes throughout Franco’s new novel, “Actors Anonymous.” Like “Palo Alto,” Franco’s debut short-story collection published in 2010, “Actors Anonymous” isn’t really a novel so much as a slim collection of short stories fleshed out with nonfiction pieces that feel about as extraneous as those Instagram stunts (but more on that later).

Franco’s stories are mostly set in Los Angeles and are mostly about actors or their friends. Is Franco aiming for an over-the-top satire of Hollywood types? If so, his angle is hazy at best. Lacking the chops to apply the sophisticated concepts that are no doubt ricocheting through his synapses, Franco does at least know how to keep his audience interested. A sense of impending doom propels each story forward.

Books: Sign up for our email newsletter

In “McDonalds I,” we meet a recovering addict who takes a job at McDonald’s, then allows the grill cook who works there to pay him for some heavy petting. The cook, whose name is Juan, “spoke no English, but I could tell from his little squeaks in Spanish that he was very stupid.” In “McDonalds II,” we pick up the same story, and our narrator has graduated to more advanced sexual favors with the grill cook, ostensibly because he needs more money to take out a pretty girl he met while manning the drive-thru.

Franco seems to enjoy walking a thin line between touching and offensive. In “Faith & Victory,” a lonely guy named Sean who dislikes even his closest acquaintances becomes a volunteer at a pediatric hospital. There he befriends a disfigured 14-year-old named Miles who was abused as a child, and the two of them shoot secret footage of the other volunteers and kids for a movie they call “Murder Hospital.”

That’s the sort of uncomfortable territory Franco seems to aim for often, whether he’s mumbling onstage at the Oscars, directing a film about necrophilia, or telling a reporter that he wishes he were gay. Like many of his public performances, though, the stories in “Actors Anonymous” lack a clear theme or a coherent narrative arc. The images Franco employs range from illustrative (“[H]e was smiling, but his mouth didn’t really smile. It just went up at the sides, and showed all his bad teeth framed by the broken flesh of his lips.” ) to willfully lazy (“Think of all of the best attributes that can be found in a young woman, and those are what she consisted of.”).

But Franco’s fiction isn’t devoid of redeeming qualities. Considering his other artistic dalliances, you might expect his stories to be heavy on pretentious flourishes and overwrought details. Instead, his work is spare and, at times, engaging. Franco’s protagonists say what they mean; they just don’t know themselves very well. This slippage between public scorn and private delusion keeps us interested, wondering what terrible fate will await these sad creatures.

If “Actors Anonymous” were an actual novel or a complete short-story collection, Franco might have given us more to enjoy and ponder.

Instead, his stories are fleshed out with bits of writing that include: 1) a series of disconnected, somewhat unoriginal statements about acting/directing/the industry (“[M]ake it about the art, not about yourself.”); 2) a reflection on his father’s death called “Tell a Lie” that segues into Franco’s (fictional?) sexual dalliances; 3) an open letter to his classmates at NYU’s film school (“I understand that some of the material in my film might have been shocking, unpleasant, or distasteful, depending on your perspective.”); 4) an angry tirade against the editors of Flaunt magazine (here referred to as “Sass magazine”), who put a close-up of Franco’s bare butt on their cover; and 5) four short poems about River Phoenix (“You’re all over the place, James./ I was a River that flowed straight/ And pure. You’re like a king/ That orders one thing,/ And then orders the opposite thing.”).

Why would Franco feel the need to gum up the works with such an unruly barrage of self-indulgent snippets? If he’s trying to link his fiction to his real life in some kind of grand prank, his attempts fall far short of the mark. By including the literary equivalent of blog entries and lengthy, enraged emails in his book, he seems to suggest that readers should find his random musings fascinating. While it’s hard not to admire his openness and enthusiasm for everything under the sun, Franco won’t be a good writer — or a great artist, if that’s his goal — until he learns how to edit, censor, politely decline and bite his tongue.

As the ghost of River Phoenix puts it in Franco’s poem, “You’re all over the place, James.” Franco himself hints that his self-obsession has begun to feel claustrophobic, but he doesn’t seem ready to do anything about it. “I hate when it’s just about me, me, me,” he writes. “But then again, I am pretty much about me.”

Havrilesky is author of the memoir “Disaster Preparedness.”

Actors Anonymous

A novel

James Franco

Little A / New Harvest: 304 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.