The book that cured me of JFK conspiracies once and for all

- Share via

For a few years after seeing Oliver Stone’s 1991 political thriller “JFK,” I was an assassination buff. I bought one of the books on which the film was based: “On the Trail of the Assassins” by Jim Garrison. I reread “Libra,” Don DeLillo’s masterful 1988 novel, in which Lee Harvey Oswald, assorted New Orleans spies and underworld figures conspire to kill the president. The assassination is the greatest mystery of our times, and in those books I found clues that left me feeling tantalizingly close to solving it.

But 20 years ago I was cured of my conspiracy-theory fever forever. A single book was the antidote.

Gerald Posner’s “Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK” was published in 1993, on the 30th anniversary of the assassination. As the title suggests, its chief protagonist is Oswald, a man with the kind of lonely, tortured and eventful biography that American culture has produced pretty routinely in the decades since. In fact, I would argue that there are echoes of Oswald’s life in figures as diverse as Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and the two teenage boys who massacred their classmates at Columbine High School in Colorado.

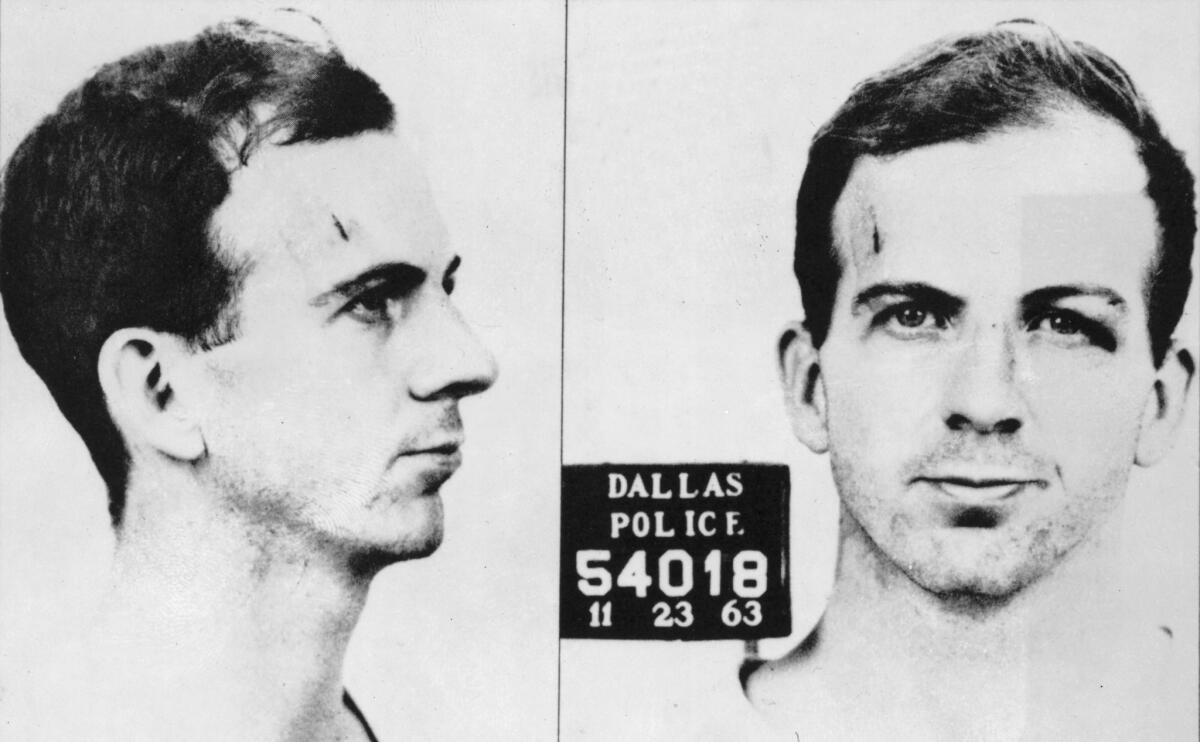

Oswald was just 24 when he was arrested after Kennedy’s assassination. In the conspiracy theories, he is a shadow figure, a pawn moved around by powerful forces, a “patsy” who takes the fall. In “Case Closed” (and also in excellent, later books by Norman Mailer and Vincent Bugliosi), a more recognizably human figure emerges. Oswald’s father died when his mother was still pregnant with him, and he had a rootless childhood, marked by domestic neglect and violence -- as an adolescent, he hit his mother and was briefly institutionalized. He latched on to various dreams and schemes to give him the sense of self his upbringing had denied him: from being a teenage “Communist” in a radical party of one, to joining the Marines and finally to defecting to the Soviet Union.

The peculiar madness of Oswald pulled me through “Case Closed,” as Posner crafts a narrative that reads like a novel -- though it’s a novel that’s being constantly interrupted when Posner has to stop and debunk the many myths about Oswald’s life that the conspiracy theorists have concocted in the years since. The famous picture of Oswald holding the rifle that killed Kennedy? Stone reminds us that Oswald said it was his head juxtaposed on someone else’s body. But Oswald’s wife took the photograph, and Oswald himself wrote an inscription on the back: “Hunter of Fascists, ha, ha, ha.” Oswald wanted to be taken seriously as a political actor, even though he lacked the social skills to be one. Before shooting Kennedy, Oswald tried to kill retired Gen. Edwin Walker, a notorious ultra-right-wing blowhard of the day. After he revealed this failed assassination attempt to his wife, Marina, the couple had an argument that Marina later related to the Warren Commission:

“I told him that he had no right to kill people… He said that this was a very bad man, that he was a fascist… When I said that even though all of that might be true, just the same he had no right to take his life, he said: ‘If someone had killed Hitler in time it would have saved many lives.’ ”

That conversation shed a clear light on the life of a small man with big dreams whose demented actions changed the course of American history. If I had not read Posner’s brave book (which ran counter to the conspiratorial conventional wisdom of its time), I would never have known about it.

ALSO:

Word of the year 2013: ‘Selfie’

Book benches to take over London. Could L.A. be next?

Just say ‘nein’: Talking with Eric Jarosinski about NeinQuarterly

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.