Is Facebook the place for serious essays? Jeff Nunokawa thinks so

Jeff Nunokawa’s book “Note Book” grew out of an ongoing series of brief essays posted to his Facebook page.

- Share via

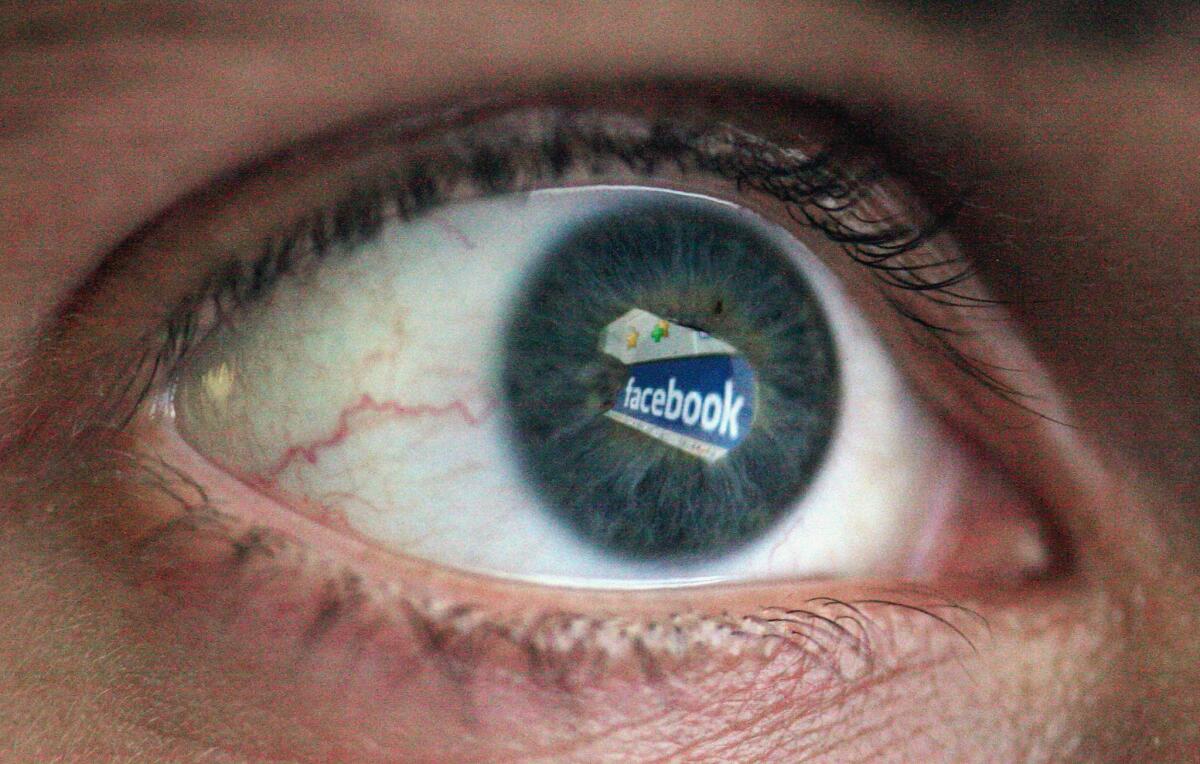

Jeff Nunokawa is obsessive. The Princeton University English professor has posted more than 4,500 small essays to Facebook, “one a day,” he writes, “over the course of what has come to be many years.” These essays are literary and they are also personal; each begins with a quotation (from a writer, mostly, but occasionally from other sources), and each also features an image, which may be explicit or oblique.

The idea, Nunokawa told Rebecca Mead of the New Yorker in 2011, is to be simultaneously revealing and discreet. “I never speak explicitly about politics,” he explained then. “I think it would be bootless, and, moreover — this is going to sound priggish, but I believe it — inappropriate. I never talk about sex, per se. There’s a self-censoring mechanism embedded in the brain — if you want to interest other people, you can’t get too personal.”

It’s a great idea, a kind of daily homily or reflection, as well as an innovative use of social media, which is too often just a source of noise. Now, however, Nunokawa has taken his obsession in a more traditional direction, gathering 250 of his Facebook essays into a collection titled “Note Book” (Princeton University Press: 336 pp., $29.95) that seeks to frame them as ephemeral and somehow lasting all at once.

That dichotomy sits at the heart of “Note Book” — the title comes from the fact that Nunokawa writes his essays in Facebook’s note function — a matter of “what is gained and what is lost,” as he suggests in an extended preface called “Initial Public Offering,” “in the work of translation from the liquidity of the Internet to the solidity of the traditional text.”

It’s a fascinating question, and never more than in regard to work that is intended to be of its moment, reactions to bits of text, lines in movies, what Don DeLillo has called “underhistory.” This underhistory, of course, represents the substance of our inner lives, which flow in response to our own set of stimuli, not necessarily historical but personal.

A 2008 essay, for instance, uses a line spoken by Gena Rowlands in a John Cassavetes movie — the exclamation, “Cold!” — to describe what he sees as a kind of bracing clarity, the way “the powers of our well-lit surface life” can allow us, at certain moments, to see things as they are.

Such a theme is echoed in a brief meditation from 2013, inspired by a line from Robert Frost, which reads: “Maybe you wonder when you first arrive: Which came first, the friendship or the flocking? But after you’ve been at the party for a while, and feeling a lot less loveless, you’re just glad to be among so many with whom you’ve come to feel at home.”

Part of what Nunokawa is after is a sense of how art and literature not just move but also transform us, by becoming a part of how we engage the world. In that sense, the essays here can be taken as close reads — if close reading can be stripped clean of analysis, taken into an emotional realm.

But even more, he is recording the slow, amorphous passage of experience, in which what we think and what we do, what we ponder and remember, make up in large measure who we are.

“Maybe we’ll get to know each other in a later life,” he writes in “vanished early”: “our root causes, our random effects and our every variation in between. Who knows, maybe what’s vanished from us will return for us in some different form, weathered and wiser and gentler now, and ready to take us back.”

That’s a lot of weight to put on a Facebook post, but that is part of the point here, to use form, technology, to our own ends, not the other way around. Why not engage at the deepest level in a territory decried as superficial? Why bend the world to our devices, rather than allow ourselves to be bound to it?

Here, we confront the key impulse — and, yes, the tension — of Nunokawa’s project, whether we come to it on the screen or on the page. How do we say anything lasting, when even the impulse to say anything is one more cry for attention — or better yet, an attempt to preserve that which cannot be preserved?

“I like finding things where nobody was looking,” Nunokawa writes, echoing Susan Sontag and Walter Benjamin. “There I was, my head buried in some old book or bad mood, and suddenly, when I was least expecting it, someone came along and took me to the place I was looking to go. Strange. I didn’t even know I was looking to go there until I actually got there.”

Twitter: @davidulin

MORE FROM BOOKS:

Stan Lee to publish memoir -- in graphic novel form

The seven books Bill Gates thinks you should read this summer

Writing and speaking come from different parts of the brain, study shows

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.