How L.A. writer Ben Loory came to write his odd, beloved fables

- Share via

There was a time when Ben Loory lived at night.

That’s how he puts it, as if night isn’t a stretch of empty hours to endure, but a place to enter, to discover whole worlds inside. After dark, the grocery stores are empty and the streets are quiet and still. The city at night is a city through the looking glass, perfect for writing, as Loory does, short stories so imaginative — and yet so perplexingly familiar — they could have formed in a dream.

“I used to wake up at 5 in the afternoon and stay up all night and write,” he said. “I still want to live at night; I just can’t really do it anymore.” Sipping a late morning instant coffee in the living room of his sunny Echo Park home, Loory’s demeanor is gentle, his voice sometimes so quiet that a plane overhead, or a neighbor’s conversation carrying through the open window, threatened to drown it out. Piles of books covered the kitchen table and a rainbow-paned quilt, hand-made by a friend, splashed across the bed. “At night, you’re just a lot lonelier,” he added, “which makes it easier to write stories about people with problems. In the daytime, everything seems fine.”

“People,” when it comes to Loory’s work, is a loose term. In “Tales of Falling and Flying,” his second collection of short stories, it may actually be a squid who’s falling in love or a dodo reckoning with identity, but the concerns and conflicts that needle these unusual protagonists are deeply recognizable: longing, belonging, connection, loss. “The things that happen in them always seem unexpected to me, but the premises don’t seem particularly out there,” he said of his stories, and yet “if there was an animated version of ‘The Twilight Zone,’ that’s what I’m doing.” His imagination is clearly rife and whirring: At one point, he referred to selling “this book to the penguins” (he is published by Penguin Originals) as if a flock of Arctic birds sits marking up manuscripts behind Manhattan desks.

Loory grew up without television, relishing Warner Bros. cartoons at friends’ houses on the weekends, but his early literary tastes remain as influential. His parents, English teachers who met in graduate school in a class on “Paradise Lost” (a hell of a creation myth for a writer), provided a house full of books. “We lived in this house way out on the edge of town,” he said. “I grew up reading all the time because that’s all that there was.” His favorite book, perhaps unsurprisingly to those familiar with his work, was “Aesop’s Fables.” “When I finished reading ‘Aesop’s Fables,’ I was like, ‘Where are the other ones? How can this just stop and why do we have to read other books?’ ”

Taut, meticulously balanced and written in Loory’s direct, witty prose, his own stories take a page from Aesop: high-flying tales nonetheless boiled down to the essentials. “Everybody knows perfectly well what makes a good story when people are telling stories, like if you’re at a party or a dinner,” he said of his tendency toward the propulsive short form. Loory’s first drafts take as little as 20 minutes, but his editing process can stretch as long as a decade. “Death and the Lady,” a meet-cute that swiftly becomes a meditation on mortality, runs about five pages and “was 10 years coming”; another story, still unfinished, has “been through 80 drafts.”

When I finished reading ‘Aesop’s Fables,’ I was like, ‘Where are the other ones? How can this just stop and why do we have to read other books?

— Ben Loory

His first collection, “Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day” was released in 2011. One story, “The TV,” appeared in the New Yorker, and he subsequently made appearances on “This American Life”; an author’s note that precedes “Tales of Falling and Flying” reads, “More Stories! Sorry they took so long.” And while Loory doesn’t exactly rush the drafting process, which is visceral — he knows that a story is complete “when I burst into tears… it’s always an emotional reaction that I didn’t see coming and can’t really explain.”

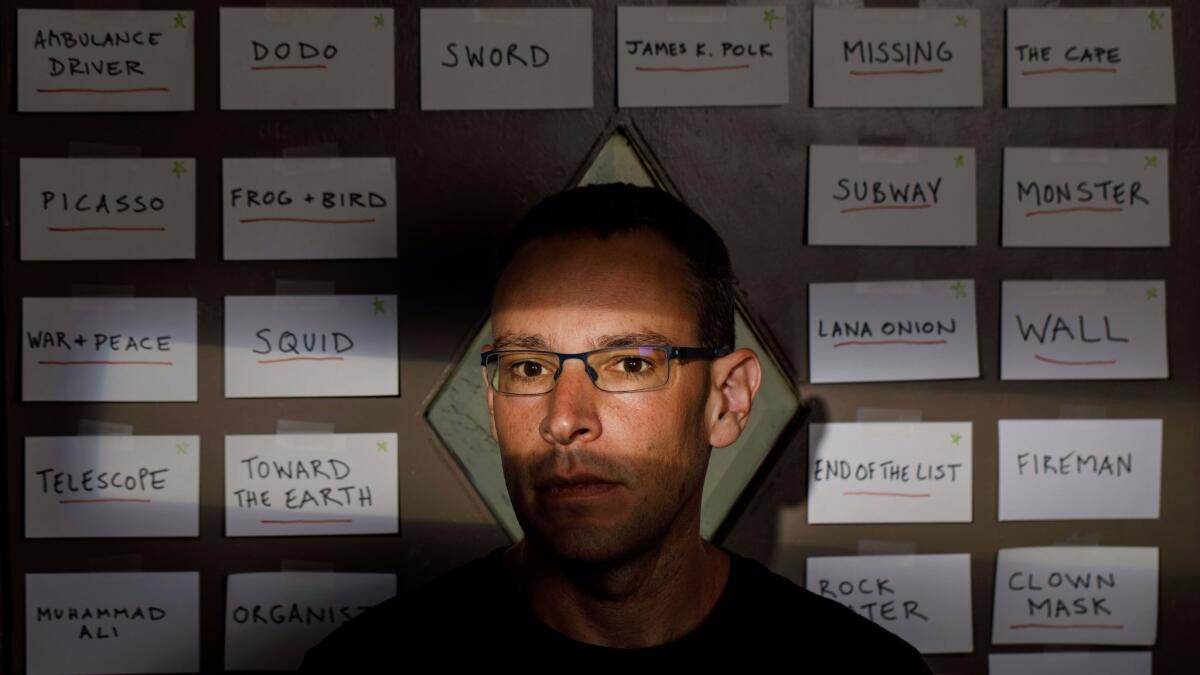

Loory came relatively late to prose writing, penning his first short story at 34 after enrolling in a creative writing class at the since-shuttered Mystery & Imagination Bookstore in Glendale. At the time, he was a working screenwriter with degrees from Harvard and AFI (hence the cue cards with working story titles pinned to his front door) looking for inspiration. “I started writing these little stories,” he explained. “And I realized that I liked them the way they were.”

He dived headlong into fiction with the ambitious goal of writing 101 stories — a play on “The Arabian Nights” — and began sleeping less and less. “After not sleeping for seven days I got very confused,” he said. “I had a manic episode,” his first and only.

As the week progressed, Loory’s grasp of reality was intermittently tenuous; he felt lucid, but someone close to him realized he was not. His distinct speaking voice — soft, but gravelly — is the result of an injury from that time. “It’s not really a very happy story, although I’m here and I am fine and I am alive,” he said.

Today Loory writes for 25-minute stints. “The timer was both to make me do it but also to make me stop doing it… and not just dive in forever.”

“Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day,” “Tales of Falling and Flying” — those titles alone allude to that diaphanous place where dusk falls or dawn rises, where falling and flying become difficult to tell apart. For all of us, the veil between reality and imagination can become thin; in his fiction, Loory captures its porousness. Themes and images reappear throughout the latest book: “The Dragon” and “The Monster” are both children’s friends, a knife in one climactic scene precedes “The Sword” in the next, and many stories end in joy, escape or laughter. “Those echoes are everywhere,” said Loory, having discovered a similar bit of dialogue (a variation of the disquieting and elemental “don’t worry… we won’t let them take you”) that appears in two back-to-back stories on the very morning of our interview. He was visibly moved by them all over again.

A teacher at UCLA Extension, Loory described his own epiphany as a new writer, a moment that clicked and which he’s held onto. “I was at the laundromat, and I had this realization that the ending of a story is the same as the beginning,” he said. “It’s like a roomful of furniture where everything is covered in sheets, and at the end you pull the blankets off of everything, and you see what was always there the whole time.” Somehow, the big reveal is that you’ve known all along, and what could be more surprising? I pointed out the narrative symmetry of daydreaming about sheets in a laundromat. Loory was delighted. He hadn’t noticed; that’s just the kind of story — whimsical, unfolding like a magic trick — that he tells.

As for writing in Los Angeles, Loory may no longer live at night, but here, in a city that sometimes feels like a world unto itself, he can visit. “It’s just a world for dreamers out here,” he said, “which is good if you want to dream.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.