Review: In ‘The Violet Hour,’ Katie Roiphe looks at five great writers shuffling off this mortal coil

- Share via

Mortality is hot. Although the act of dying has largely been moved from our homes and daily lives into the sequestered, antiseptic realm of hospitals and hospices, memoirs grappling with impending death have proliferated, bringing mortal knowledge home in a new way.

Two doctors, Oliver Sacks and Paul Kalanithi, recently wrote beautifully and unflinchingly about their struggles with insurmountable cancer, as did Christopher Hitchens. This year, Marion Coutts’ “The Iceberg,” an intense account of her husband’s death from a brain tumor, joined a raft of gorgeous spousal tributes, including Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking,” John Bayley’s “Elegy for Iris,” and Calvin Trillin’s “About Alice.”

Katie Roiphe’s “The Violet Hour,” which takes its shimmering title from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” is an analytical blend of journalism, literary criticism and memoir that — like her earlier book, “Uncommon Arrangements,” about unconventional literary marriages — tackles a personal obsession. By closely examining the demise of five writers who have long fascinated her, Roiphe hopes to defang death, which has haunted her since an early brush with mortality when she was 12. She focuses on Susan Sontag, Sigmund Freud, John Updike, Dylan Thomas and Maurice Sendak, although she acknowledges that there were many more who tempted her, including Honoré de Balzac, Leo Tolstoy and Virginia Woolf.

Each essay begins at death’s door, rolls back time to explore the writer’s attitudes toward mortality before they were up against it, and finally describes their final moments on this mortal coil. Like death, the essays end with startling abruptness.

“In my head I think of what I am doing as biography backward, a whole unfurling from a death,” Roiphe writes in her prologue, which explains her therapeutic impetus and provides such a detailed summary of her project that the actual essays occasionally seem redundant.

Drawing on the writers’ work, letters and interviews with their families, friends and caretakers, her book is at once scholarly, literary, juicy — and unabashedly personal. But despite Roiphe’s admiration for her subjects’ work, these portraits are no hagiographies.

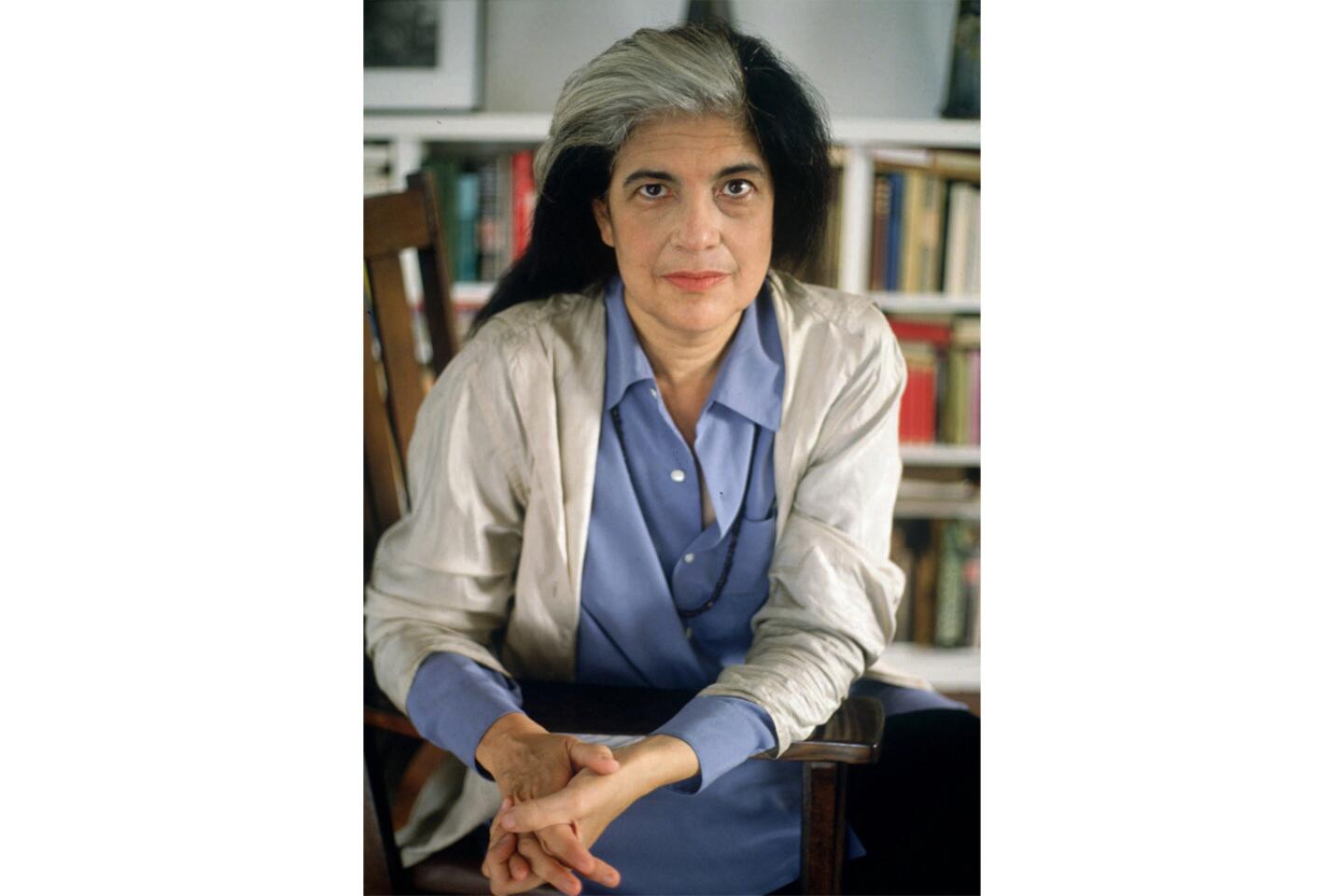

Sontag, the only woman of the group, is depicted as “self-mythologizing,” attention-seeking and the fiercest death-denier. In her essay “Illness as Metaphor,” Sontag argued for “clarity, rational thought, and medical information” when confronting disease — as opposed to romantic mythologizing. This was clearly Sontag’s no-holds-barred approach to her multiple cancer diagnoses. Roiphe argues that Sontag’s odds-defying survival of stage 4 breast cancer in the 1970s and uterine cancer in 1998 “fed into her long-standing idea of herself as exceptional.”

These earlier survivals also fed Sontag’s fierce determination to fight the blood cancer with which she was diagnosed in 2004. Despite her doctor’s hopeless prognosis, the 71-year-old writer dragged herself — and her loyal but skeptical support team — through miserable, aggressive treatments, including a torturous, doomed bone marrow transplant.

Roiphe’s portrait of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas is more sympathetic, if hardly more flattering. We meet him the day before his death in 1953, in a coma at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village — possibly the result of downing 18 whiskeys in one night. With typical lively hyperbole, Roiphe writes, “Half of literary New York was gathered outside his room, as if they were still at one of the roving drinks parties that sprang up spontaneously around him.”

After setting the scene, she traces Thomas’ long-standing fascination and flirtation with death through his dissipated life and his “ripe lyricism,” exemplified so richly in his most famous poems, “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” and “Fern Hill.” Roiphe writes, “At some point, the poet’s morbid and overblown fear of death transformed itself into barreling headlong toward it.” Yet her portrait of this womanizing, “self-destroyed escapologist” is softened by her high regard for his lush language.

For Roiphe, John Updike has a different kind of appeal: “I have a soft spot for those who try to defeat death with sex,” she writes. In his early books, Updike wrote of sexual adventure as an antidote to death, a way of “grasping at life.” She captures him, diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in late 2008 at age 76, urgently struggling, “transforming pain into honey” once more in his final volume of poems, “Endpoint.”

To reconstruct her authors’ dying days, Roiphe had to press their survivors for private details, resulting in some intriguing portraits of a variety of caregivers. While Updike’s second wife, Martha, comes across as a dismayingly fierce barrier between her husband and the family he abandoned for her, Roiphe describes Maurice Sendak’s dedicated longtime live-in housekeeper and companion, Lynn Caponera, as “a fantasy of a mother who would be eternally available … dispensing an unconditional and undemanding love.”

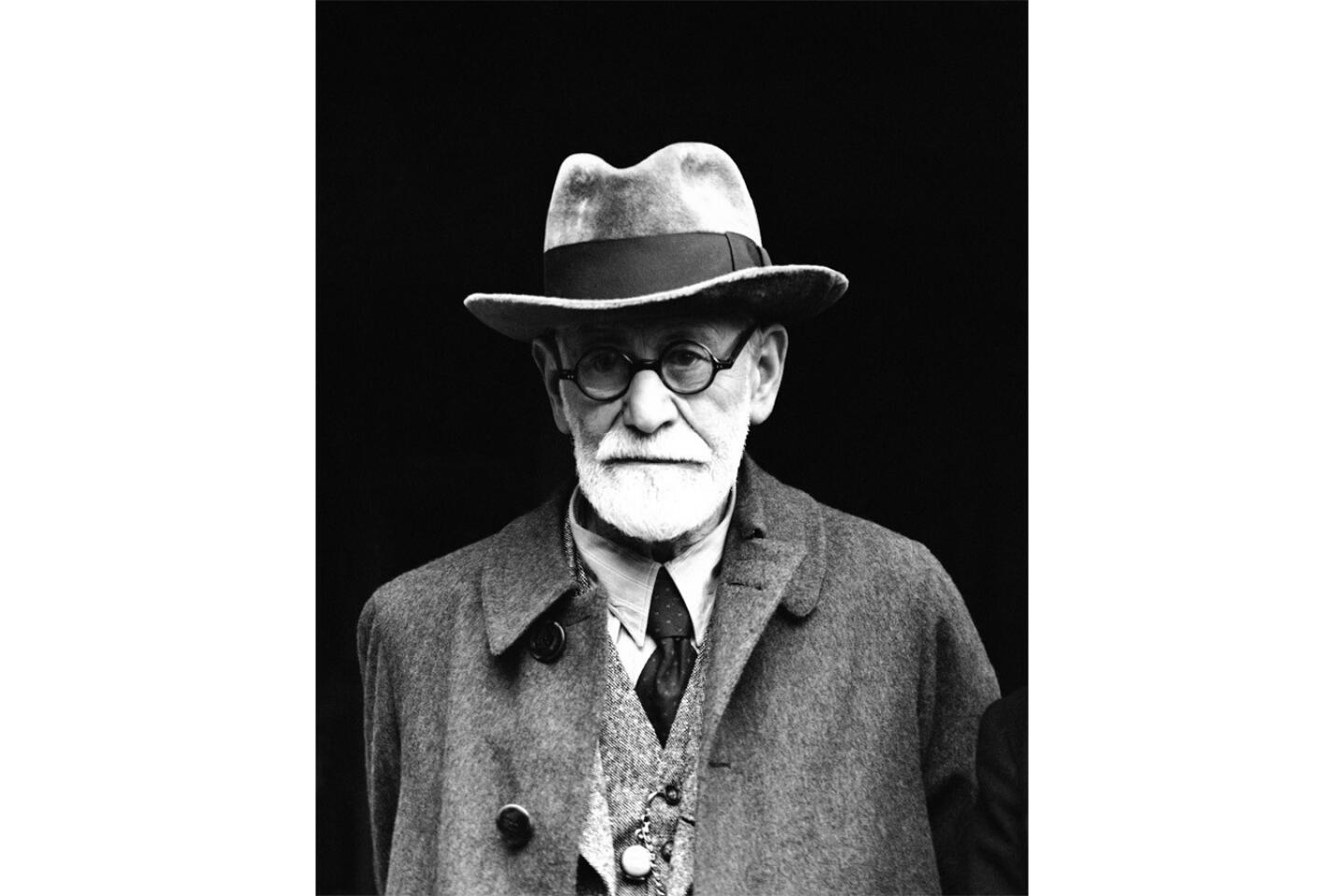

Freud had his devoted daughter Anna in attendance, but he called the shots. Rational and analytic to the end, he refused painkillers stronger than aspirin for his excruciating throat cancer: “I prefer to think in torment than not to be able to think clearly,” he said. Unlike Sontag, he “did not like the idea of prolonging life at all costs,” Roiphe reports admiringly. In fact, like Sendak, he announced he’d had enough when he was no longer able to work.

This unconventional, engaging book is clearly a form of therapy for Roiphe. “As I was working on them, I found the portraits of these deaths hugely and strangely reassuring. The beauty of the life comes spilling out,” she writes.

Readers are apt to find more emotional sustenance in searing first-person accounts of impending death like Kalanithi’s “When Breath Becomes Air.”

Although “The Violet Hour” is unlikely to move you to tears, it sure offers plenty of thought-provoking psycho-literary analysis and intimate biographical details to satisfy your morbid curiosity.

McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR.org, the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.

::

The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End

Katie Roiphe

Dial: 320 pp., $28

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.