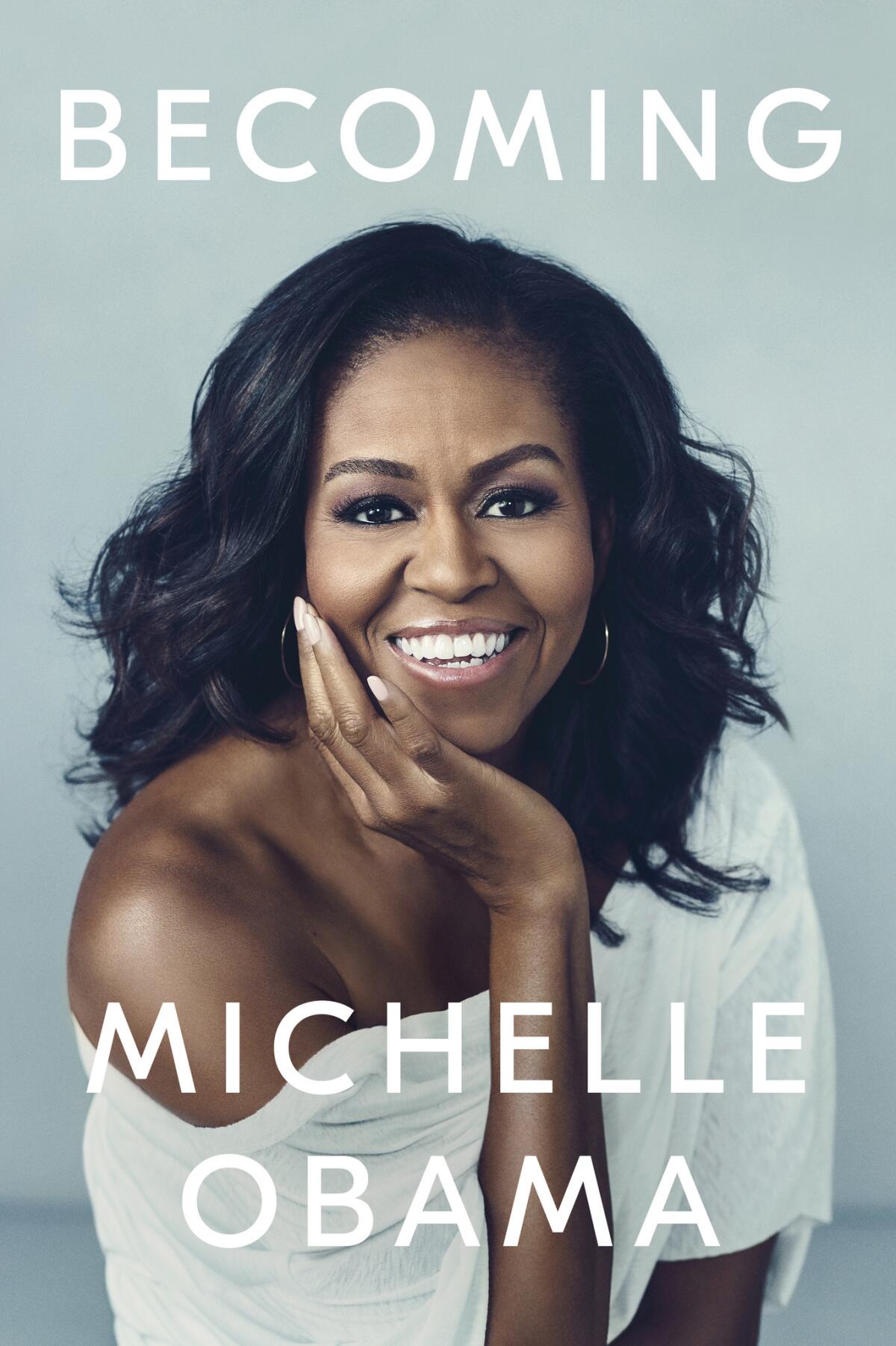

Michelle Obama’s ‘Becoming’ is a clear, frank telling of her life as a black woman in America

- Share via

James Baldwin wrote, “No one can possibly know what is about to happen: it is happening, each time, for the first time, for the only time.” This went doubly for Michelle Obama, who decided against reading books by other first ladies when her husband was president. “I almost didn’t want to know what was the same and what was different about any of us,” she writes in “Becoming,” her ardently anticipated, Oprah Book Club-selected, 400-page memoir. But of course something was different for Michelle and Barack Obama. Real different.

“Optics would always rule our lives,” writes Michelle, some ways through Obama’s first presidency term. She meant it in reference to their positioning and movement and choices in the White House as a black First Family, but there isn’t a black person on the planet who doesn’t have an acute awareness of this reality — of being followed and monitored and assessed. The Obamas endured this publicly sanctioned scrutiny for eight years, at the end of which, a whole lot of us wished they’d take us with them, wherever they may be headed.

When the Obama family left the White House in early 2017, I was a guest on a culture and politics podcast and was asked if I thought a book might be in Michelle Obama’s future. I responded with casual confidence, perhaps unconsciously protective of the genre, or, more likely, deluded into thinking by her appeal and accessibility that she is my BFF and I just know her like that: “No, Michelle is not a writer. And I think she knows that about herself.”

Obviously, I was wrong about her writing a book, but I don’t think I was wrong about her not being a writer, at least not in the lofty, traditional sense. In “Becoming,” Obama doesn’t write so much as talks to her readers as she always has to a nation that fell in love with her — in clear, frank and forthcoming terms, as a black woman in America with a bridge called her back and a wisdom to lay bare.

“My job, I realized, was to be myself, to speak as myself.” It was her first solo campaign speech, given in 2007 in Des Moines to support then-Sen. Barack Obama’s bid for president. “And so I did.” That speech was particularly memorable not just because she spoke from the heart, but because she had found her agency in that particular role as more than just a politician’s wife, and you could feel it. “The more I told my story, the more my voice settled into itself.” It’s a pivotal moment both then, in real time, but also in the book. “I liked my story. I was comfortable telling it.”

It took some doing to get there, though. Split up into three parts — “Becoming Me,” “Becoming Us,” and “Becoming More” — the book is a fairly linear account that spans from her well-documented roots on the black working-class South Side of Chicago, to meeting Barack, and then moving to the White House as the country’s first black First Family.

“I spent much of my childhood listening to the sound of striving,” her story begins. “The sound of people trying … became the soundtrack of our life. Michelle Robinson grew up with her close-knit family in a one-bedroom, second-floor apartment in a brick bungalow owned by her great aunt, Robbie, who lived on the first floor with her husband, Terry, and taught piano lessons to neighborhood children with an audibly exacting tenor. The sound of Robbie’s sharp instruction and the piano keys plinking on the floor below formed a constant aural backdrop, one that resonated with young Michelle as a guiding principle. For black folks, striving is in the memory bones — an emotional elegy that withers and wanes, but that is always there, passed down from one generation to the next. And as loved as she felt by her sensible and hardworking parents, as well as her adoring older brother, for Michelle, to strive was to breathe, to be validated.

Even after she arrived at Princeton University — despite her high school guidance counselor’s suggestion that she might not be “Princeton material” — Michelle’s hustle was all-consuming. “Beneath my laid-back college-kid demeanor, I lived like a half-closeted CEO, quietly but unswervingly focused on achievement, bent on checking every box. My to-do list lived in my head and went with me everywhere. I assessed my goals, analyzed my outcomes, counted my wins. If there was a challenge to vault, I’d vault it. One proving ground only opened onto the next. Such is the life of a girl who can’t stop wondering, Am I good enough?”

Today it’s perhaps hard to imagine Michelle Obama, our “Turn up for what?” fearless FLOTUS, as wondering whether or not she is good enough, but it’s also undisguised evidence that she was once a black girl in America. And that is why black girls and women all over the world were immediately drawn to her — because she never forgot that little black girl she once was, both in playful and serious terms, and we saw ourselves reflected in her. Not just in an aspirational way, in a lived way.

That said, we probably could have seen ourselves reflected in about 100 fewer pages. A few parts of “Becoming” read as overly detail-oriented and impersonal (“having been dispatched to help prepare a case … my life was wholly dedicated to sitting in that room … opening file boxes that had been shipped from the company headquarters, and reviewing the thousands of pages inside”) — maybe a practiced instinct from her days of writing legal memos.

But she more than makes up for any moments of remove as soon as Barack comes onto the scene, because she clearly was not ready for this freewheeling guy from Hawaii with a funny name, who immediately brings out the best in her. Michelle’s sense of humor blooms (of Barack’s self-certainty, she writes: “All this inborn confidence was admirable, of course, but honestly, try living with it.”), and her love for Barack is palpable: “As soon as I allowed myself to feel anything for Barack, the feelings came rushing — a toppling blast of lust, gratitude, fulfillment, wonder.” Well OK then, girl.

Much has been made of the passage in the book where Michelle shares her struggles to get pregnant, the suffering of a miscarriage, and the in vitro fertilization treatment that brought her Malia and Sasha, which is absolutely remarkable and important in terms of a broader conversation about black women’s bodies and reproductive health. But I was actually more struck by the smaller moments in which Michelle shows an equal, if not obvious, kind of vulnerability. A friend calls to say she has just come from visiting with their cancer-stricken mutual friend, and tells Michelle she combed out their friend’s hair. “That Suzanne needed to have her hair combed should have told me everything, but I’d walled myself off from the truth.” When an adult black woman needs to have her hair combed through in the same ritualistic manner as when she was a child between the knees of her mother, something is amiss. But even more, it signals a kind of intimacy known only to family and close friends.

After their engagement, Michelle and Barack travel to Kenya to meet Barack’s extended family on his father’s side. When Michelle is first introduced to Barack’s grandmother, Granny Sarah asks Michelle, “Which one of your parents is white?” Michelle, in Africa, a place that gave her “a hard-to-explain feeling of sadness,” writes, “I laughed and explained … that I was black through and through, basically as black as we come in America.” There’s so much in that statement, when she is standing alone in her pride, her heritage, her appeal, her earned sense of self, her unequivocal blackness.

In the last part of the book, it’s easy to get effectively as swept up as Michelle does in the whirlwind of the presidential campaign, their uprooting from Chicago and move to the White House, settling their girls in schools and worrying about their safety, wrestling with the fact that “[e]verything was big and everything was relevant.”

And everything, surely, was evolving. Becoming. What is revelatory is that by the end of “Becoming,” who Michelle Obama was before she was FLOTUS is a woman you feel glad and grateful to have back in our midst — the striver, an astonishing mix of resilience, joy, pragmatism and grace.

Carroll, one of the Times’ Critics at Large, is editor of special projects at WNYC. Her memoir “Surviving the White Gaze” is coming from Simon & Schuster in 2020.

Michelle Obama

Crown: 429 pp., $32.50

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.