Harry Mathews’ posthumous novel ‘The Solitary Twin’ is a fascinating, discursive swan song that celebrates the power of stories

- Share via

There are writers who can draw out a yarn like Scheherazade, perhaps in some vain hope that the contours and detours of a discursive story might forestall death as it had on those thousand and one nights. In “The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman,” Laurence Sterne has his titular narrator, one of the ur-digressors of the novel form, explain, “Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine; — they are the life, the soul of reading! — take them out of this book, for instance,—you might as well take the book along with them; — one cold eternal winter would reign in every page of it.”

A list of Sterne’s digressive progeny would be as stylistically varied as it is long: Think Herman Melville’s deep-dive asides, Marcel Proust’s streams of involuntary memory, Henry Miller’s perpetual spirals of free association, Nicholson Baker’s meandering meditations stretching like taffy a character’s small moments, Zadie Smith’s hysterical realist excursus, David Foster Wallace’s footnote pyrotechnics, or Harry Mathews’ matryoshka dolls nesting stories within stories.

Early last year, Mathews, the first American ever welcomed into Oulipo — that French society of experimental, constraint-based “potential literature” founded by the likes of Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais — died at the age of 86 from natural causes. There was no mystery in his end except the mysteries that always cocoon around death, things left unresolved.

It’s always a shock to see our literary heroes and forebears pass, but there’s something particularly disjointed when the writer who dies is a digressive novelist: The life, by ending, refuses to mirror the writer’s dominant aesthetic principle of continuing to go on and on and on.

“The Solitary Twin,” released this month by New Directions, acts as coda to Mathews’ idiosyncratic career — a short work that succeeds as both a career-end capstone and a final digression. In this fascinating swan song, a psychologist who has “a penchant for cracking open every nut for study” and a publisher, a purveyor of stories, become lovers when they meet on a visit to an “extenuated fishing village of immemorial origin.” This pair of lovers, Berenice and Andreas, connect in more than mere carnal passions; they unite in a common goal of unraveling the strange story of the town’s most notorious residents: a set of “twins, as identical as can be,” that are never seen together, never interact, avoid each other at all costs. Though both brothers, Paul and John, are well-liked in town, some residents “find their behavior more than a little upsetting.”

For all the strangeness of their separate lives and uncrossed paths, these twins, we are told, “do share one very visible companion, who might well act as a go-between”: Wicheria, the lover of both twins, who further complicates an already complex mystery.

While this mystery surrounding the twins electrifies the book, the majority of this clever, protean novel is comprised of the stories told at dinner parties and meet-ups among new and old friends: “Stories that we’d love to tell or retell ourselves or, perhaps more accurately, that we’d love to hear told.”

At one such gathering, Berenice admits: “We’re very into stories, life stories especially.” The desire for stories — a hard-wired human impulse — is one that Mathews is more than happy to satiate.

Not only is he happy to satiate this desire, but it’s a task he’s shown over and over that he is more than qualified to fulfill. Earlier novels — including the mysterious riddles that invigorate “The Conversions,” the rip-roaring prison-escape adventures of “Tlooth” and the latticework of intersecting couples in “Cigarettes” — likewise seem constructed from stories that beget stories, digressions that breed digressions, mysteries that evoke more mysteries, gaps that open up into ever-widening gaps.

In one of these stories told over dinner, a man identifies another hard-wired human impulse: “the desire to resolve the irresolute, to conclude the incomplete, to have the crooked made straight.” In short, we want to understand everything. We want to make sense of the world. We want complications made tidy. This is a desire Mathews seems less interested in satiating.

That isn’t to say that there aren’t answers to be had in “The Solitary Twin.” In fact, it could be argued that this is one of his most accessible novels. As the book spirals ever closer to some explanations to its central questions, “The Solitary Twin” begins to resemble the twisted thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock as much if not more so than the work of his Oulipo brethren, Georges Perec, Italo Calvino and Jacques Roubaud.

Yet while this slim novel does allow some answers, it leaves much unresolved — not unlike Mathews’ death. Death is always unresolved, incomplete — even if it is, by definition, life’s ultimate conclusion. Those of us left behind — even if we understand all the facts, the details, the nuances — remain perplexed, uncertain of the full meaning or implications. We are forever weighted by our wonder. To go on, we must continue to ponder, even in the face of perpetual unknowing, and in doing so, it is crucial that we give and receive stories. Our human impulse for stories is the closest thing we have to a corrective for our insatiable appetite to resolve that which will forever remain irresolute.

Mathews’ death may darken our skies, but his writing continually offers what Sterne called the sunshine, the life, the soul of reading. One cold eternal winter does not reign on a single page of Mathews’ final novel because the stories continue, the digressions go on, and even though Mathews the man has passed away, Mathews the writer, the storyteller, continues — a now solitary twin.

Malone is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Scofield and a contributing editor for Literary Hub. His writing has appeared in the LA Review of Books, Lapham’s Quarterly, and elsewhere.

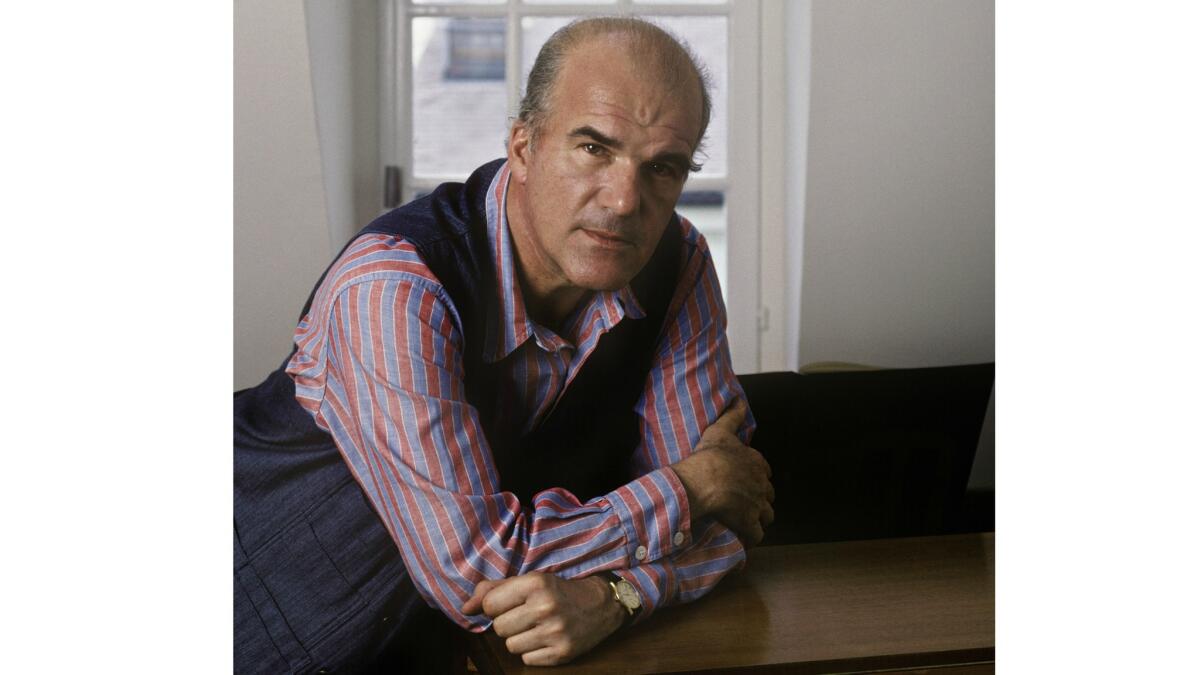

Harry Mathews

New Directions: 160 pp., $15.95 paper

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.