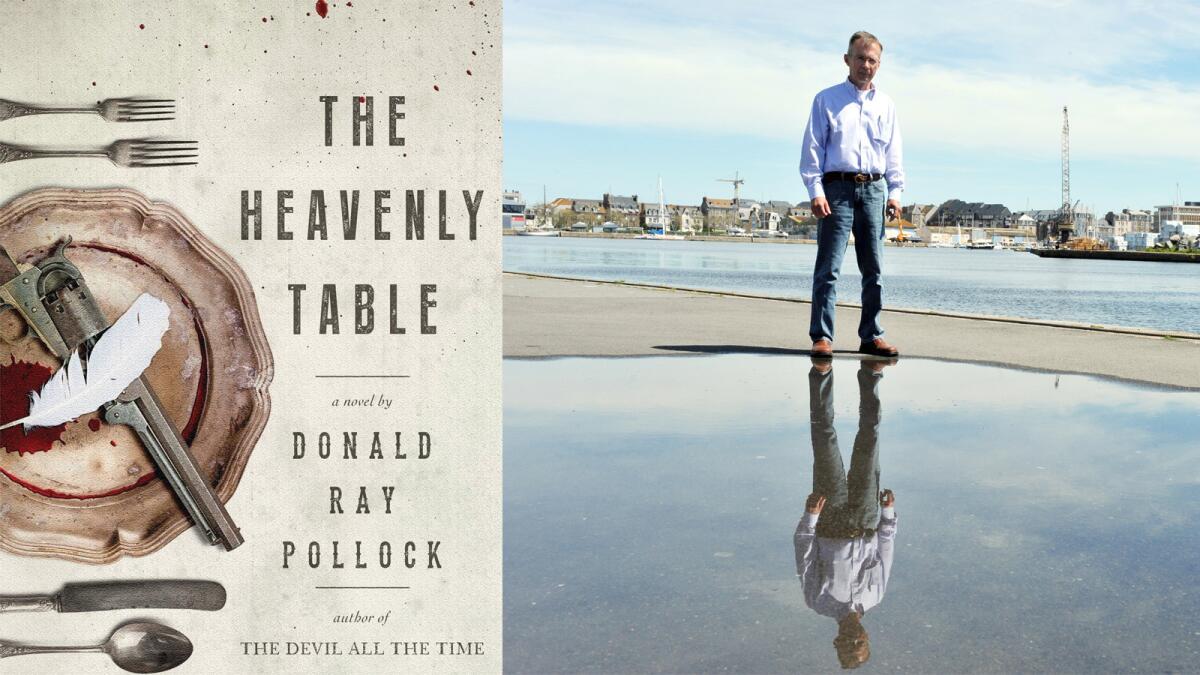

Donald Ray Pollock’s ‘The Heavenly Table’ is brutal American Gothic literature

- Share via

There are few living novelists with a stronger point of view than Donald Ray Pollock. After working 32 years in a paper mill in Chillicothe, Ohio, Pollock got his MFA in his 50s and in 2008 published “Knockemstiff,” a harrowing collection of short stories named for his hometown in southern Ohio. His first novel, “The Devil All the Time,” was a masterful follow-up, mining the same dark depths with a sharper eye for narrative arc. With these two books, Pollock established himself as one of the leading scribes of a new generation of American Gothic literature, full of rugged prose, desperation and decadent violence.

His latest, “The Heavenly Table,” takes place in 1917 from the border dividing Georgia and Alabama to Pollock’s own Ross County in southern Ohio. It revolves primarily around the three Jewett brothers, who leave their lives of abject poverty and subordination to go on a crime spree, influenced by a fictional “crumbling, water-stained dime novel” called “The Life and Times of Bloody Bill Bucket.” Cane Jewett is the eldest at 23, the leader and only literate one, as well as the only one who possesses both intelligence and a mostly functional moral compass. The middle brother, Cob, is slow-witted and childish — “there weren’t enough brains in his head to fill a teaspoon” — while Chimney, the youngest, is rash and unpredictable, with a chilling tendency toward cruelty.

But it’s desperation, rather than blood lust, that compels the Jewett brothers to turn to crime. At the novel’s opening, the brothers and their father, Pearl, are working at starvation wages for an exploitative landowner. “There would be no more to eat until evening, when they would all get a share of the sick hog they had butchered in the spring, along with a mash of boiled spuds and wild greens scooped onto dented tin plates with a hand that was never clean from a pot that was never washed. Except for the occasional rain, every day was the same.” Years after the death of his wife — a grotesque death, involving a giant parasitic worm — Pearl believes in forbearance in the present life, in anticipation of an eternity of feasting at “the heavenly table.” When Pearl drops dead in the middle of a sick-pig-induced bout of diarrhea, Cane and Chimney hatch a plan to relieve their landlord of some horses, rob a bank and ride to Canada.

Of course, things don’t go as smoothly as Cane hopes (“In all the months of imagining their escape, nobody had gotten hurt. At least not on the first goddamn night. How could he have been so stupid?”) The Jewetts get their horses and run, but only after a bloody encounter that sets the tone for the rest of their journey. And yet it’s hard not to root for them — as Bloody Bill Bucket suggests, “the world was an unjust, despicable place lorded over by a select pack of the rich and ruthless, and the only way for a poor man to get ahead was to ignore the laws that they enforced on everybody but themselves.”

The Jewetts are not the only ones down on their luck — over the course of the novel they interact with dozens of people, many of them beaten, destitute and victimized (both before and after the gang gets through with them), who paint a grim, engaging portrait of World War I-era Middle America.

In southern Ohio, Ellsworth Fiddler loses $1,000 — his family’s entire life savings — in a cattle scam: “two months after the swindle, he overheard [his wife] say to herself, ‘Just have to start over, that’s all.’” At an Army camp in Meade, Ohio, a young classics scholar deals with his homosexuality and his desire to die on the front lines in Europe; nearby, a pimp with hopes of marketing “The Celestial Harem of Earthly Delights” settles for the lowlier “Whore Barn.” A black drifter trying to get on his feet runs into both the Jewett Gang and the posses hunting them for reward money; a serial-killing bartender complicates things for everybody.

Pollock is a gifted writer with a unique sensibility and a captivating style. His prose is gritty, his dialogue entertaining: “My God, Ells, you’re talkin’ about a man who once ate a dog turd at Jack Eliot’s fish fry for a pint of moonshine.” Sentence for sentence, he is an absolute pleasure to read.

But “The Heavenly Table” stalls in a way that Pollock’s other books do not — it drifts far afield of its central narrative, with a huge cast of characters who get back stories and points of view. Whole chapters are dedicated to one-off randos, like the geologist from New Haven with a dead brother and conservative father whose only role in the book is to stumble on a dead body (the dead body also gets a back story). There are several unimportant characters who get single point-of-view paragraphs, like the retired Presbyterian minister who shows up just long enough to tell us he has dementia. What’s more, almost all of the characters are male. This sprawling structure ends up feeling less like a “Winesburg, Ohio”-style survey than a novel written in undisciplined 1,000-word sprints.

The plot is also rather unruly, but it’s hard to begrudge Pollock his excesses when he writes violence and black humor so well (“[He] stepped back and swung the machete again, burying the blade in the back of the man’s thick, meaty neck, but he remained upright, his eyes blinking rapidly and his mouth opening and closing like a landed fish sucking air. The boy tried to jerk the knife loose, but it was wedged tight between two vertebrae.”) Incredibly, both of his novels include multiple instances of murderers happening upon other murderers — the Jewett Gang has run-ins with at least four other killers.

“The Heavenly Table” has a pulpy, outsize quality, and the Jewett brothers find there’s value, even truth, to be found in extreme stories: “Though [Cane] had always known it was just an outlandish tale … it had still given them hope when there was none, something to aim for that was bigger than the life they’d been handed.” “Bloody Bill Bucket” inspires the Jewett Gang to abandon their father’s ways and force much-needed change into their lives — as Cob holds a coveted ham, “It was like something he’d imagine you’d find on the heavenly table, in between the roast beef and the spare ribs, but instead it was right here, in his dirty hands.”

“The Heavenly Table” is less likely to inspire would-be bank robbers, but it contains enough poignant and vile humanity to leave a long impression. Even though the novel may not be his best, it’s a book that can only have come from Donald Ray Pollock, who remains one of our most intriguing working writers.

Cha’s latest novel is “Dead Soon Enough.”

::

By Donald Ray Pollock

Doubleday: 384 pp., $27.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.