Column: The profiteering dialysis industry made big bucks from killing Proposition 8. Here’s how

- Share via

Big companies don’t normally invest tens of millions of dollars with the expectation of losing. Case in point: The multimillion-dollar investment by two big dialysis companies in the killing of California’s Proposition 8.

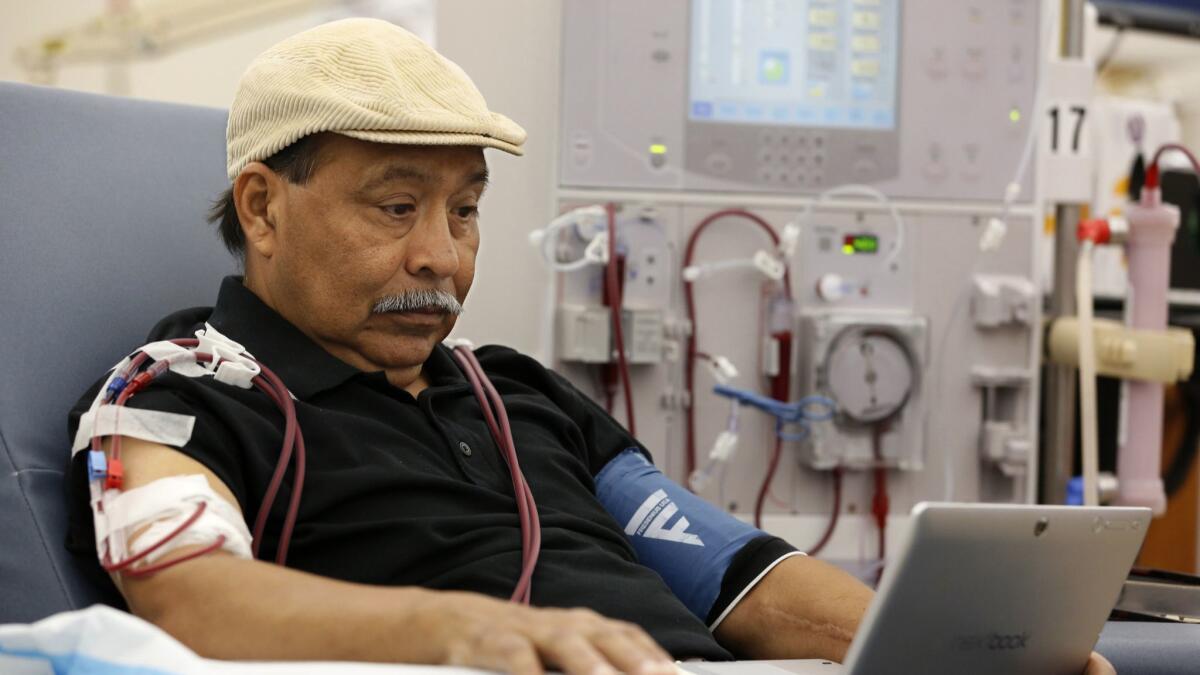

The ballot initiative, which was sponsored by the Service Employees International Union (which is trying to unionize dialysis clinic workers) would have capped the revenue of for-profit dialysis providers while creating incentives for them to hire more patient-care staff and pay them better. Doing what comes naturally to profit-seeking businesses, the dialysis industry assembled a war chest of more than $111 million—a national, historical record — and won, defeating the initiative by a nearly two-thirds margin.

The question is whether this was money well-spent for them, and the answer is: You bet it was.

The industry’s two leading companies, Denver-based DaVita and the German healthcare conglomerate Fresenius, together accounted for $95.5 million of the industry’s spending against the measure. DaVita donated about $67 million and Fresenius $27.5 million, according to the latest figures from the Secretary of State.

The harvest can be measured in their stock prices. Measured against Monday’s pre-election close, DaVita’s shares soared 10.95% on Wednesday, the day after the election, closing at $76.08. They’ve since fallen back to $69.35 in midday trading Friday, still a gain of 1.14%. In terms of market capitalization, DaVita gained $1.37 billion in value Wednesday, as of this writing is still $142 million to the good. That puts its $67-million investment in the No on 8 campaign firmly in the black.

Fresenius also is a winner. Its shares gained 9.3% as of Wednesday, when they closed at $43.17. As we write, they’re at $40.19, a gain of 1.75% over Monday’s close. In terms of market value, Fresenius gained $1.1 billion on Wednesday compared with Monday, and is still holding on to a gain of $214.6 million. Also in the black.

It’s one thing to count up the gains from a successful No campaign, but one should also consider the what-if. Had Proposition 8 succeeded, it’s a fair bet that the shares of both companies would have cratered, both because of the paring of their California revenues and the possibility that other states would follow suit. So even if the immediate stock rises don’t last, the companies almost certainly have better prospects for revenue and profit growth than they would otherwise have had.

It’s proper to observe that companies generally don’t directly profit (or lose) from changes in their share price on the open market. But rising prices benefit them indirectly in many ways. They’re a signal of positive sentiment among investors, which is always good for business. They make it easier to raise new capital at lower cost. If a company pays for an acquisition with its stock, obviously it’s better to have a higher-valued currency to spend.

For the CEO and other top executives, higher share prices can have a more direct effect — they factor into the executives’ annual compensation, even if not explicitly, and they raise the value of shares awarded to the executives as part of their pay. Senior executives typically hold sizable equity stakes in their companies; Kent Thiry, DaVita’s chairman and CEO, held more than 945,000 shares in the company as of March 31.

So it’s indisputable that the defeat of Proposition 8 served the interests of DaVita, Fresenius and other dialysis providers. The question is whether it served the public interest.

For perspective, one should keep in mind the behavior of the dialysis industry in recent years, as we documented in earlier columns here, here and here.

These are quintessentially self-interested players in healthcare that arguably have gamed Medicare and the Affordable Care Act to pump up their own profits, at the expense of all healthcare consumers and the government. To do so they undermined the very concept of philanthropy, by allegedly bending a purported charity, the American Kidney Fund, to their own corporate purposes.

The No on 8 campaign commercials on television played ruthlessly on voter fears that the measure would force hundreds of California clinics to close. That’s an assumption based entirely on a study that the dialysis industry labeled “independent,” but which they paid for to the tune of $200,000.

Editorial writers across the state, including at The Times, counseled readers to vote no on Proposition 8, generally because it was a union-sponsored initiative — a remarkably blinkered approach that failed to take into account the relentless profiteering of firms such as DaVita and Fresenius.

Is this the way we want our laws to be made? Hand-wringing over corruption in politics generally focuses on the suborning of politicians by rich benefactors. The fate of Proposition 8 reminds us that worse corruption of our political system takes place further down the ballot, in an initiative system deeply infected by greed.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.