Column: Liberals should stop attacking Bernie Sanders for targeting Jeff Bezos and Amazon. He’s on the right track

- Share via

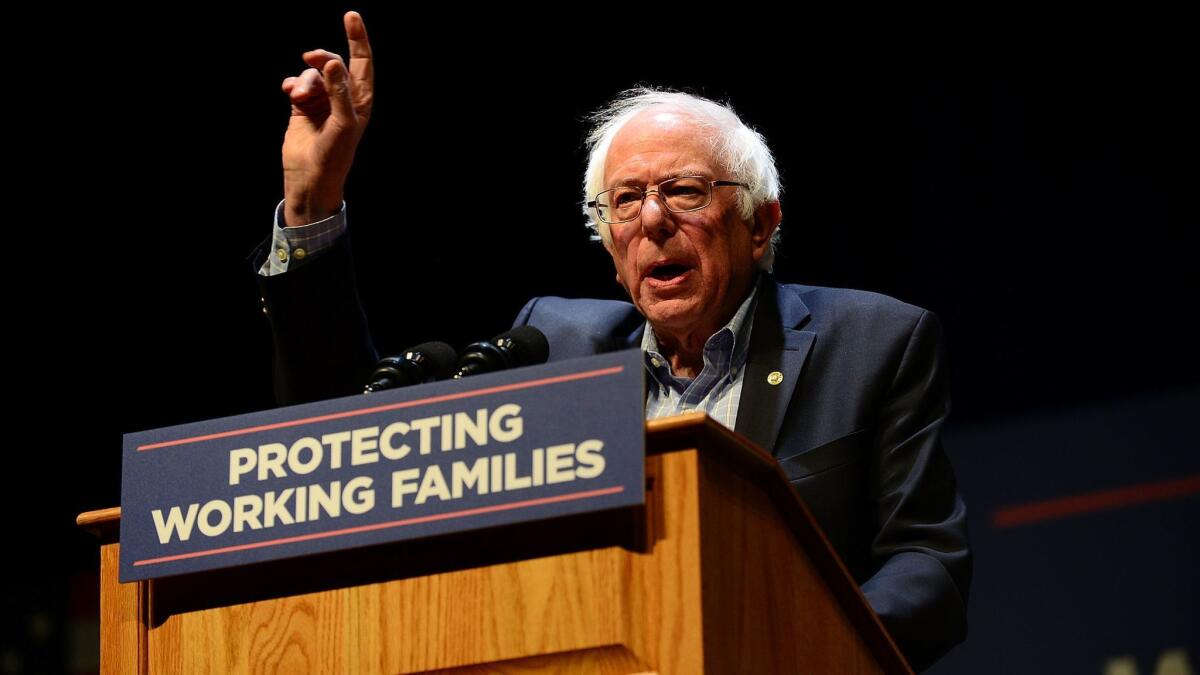

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) set the policy world ablaze a few days ago by introducing a measure he called the “Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies Act.”

If you noticed that the title reduces down to the “Stop Bezos Act,” congratulations: Sanders and his co-author, California Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Fremont), meant to focus attention on how Bezos’ enormous company, Amazon.com, employs thousands of workers at such low wages that they turn to public assistance programs such as food stamps and Medicaid for their basic living needs.

The Stop Bezos Act would impose a dollar-for-dollar tax on Amazon, Walmart and other such low-wage employers for the cost of their workers’ public benefits: If an Amazon worker’s family received the national average benefit of $3,000 from the Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, the formal name for food stamps), Amazon would pay a tax of $3,000.

The working families and middle class of this country should not have to subsidize the wealthiest people in the United States of America.

— Sen. Bernie Sanders

“The working families and middle class of this country should not have to subsidize the wealthiest people in the United States of America,” Sanders said on introducing the act, referring to Bezos and the Walton family that owns Walmart, who are billionaires. “That’s what a rigged economy is all about.”

One would think that Democrats and progressives would praise Sanders for this legislative initiative. After all, Amazon’s employment of low-wage workers, its baleful influence on communities and the punishing working conditions in the warehouses from which its merchandise is shipped to customers have been amply documented. Instead, they’ve turned their fire hoses full-blast on Sanders himself. The drawbacks of his proposal have been picked apart to a fare-thee-well by some of the nation’s leading progressive think tanks, including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The critics aren’t wrong about the proposal, exactly. They’re just allowing themselves to be distracted by the details of a legislative proposal that on the gonna-happen scale is a “not.” So they spend a lot more time and effort on those details than on the underlying issue. It’s a bit like what happens when you try to draw a dog’s attention to something by pointing at it with your finger; he stares at your finger.

In this case, the underlying issue is the inequity of low-wage employment in the United States, and the degree to which big companies reap unjust profits from it. That issue, and the right way to address it, generally receive a few paragraphs of attention at most in the white papers informing us of all the reasons the Stop Bezos Act can’t possibly work.

A similar fate has befallen the proposal by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) to require most public companies to obtain a federal charter requiring them to turn over 40% of their board seats to employees, among other provisions aimed at directing managements to pay more attention to the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders.

Warren’s proposal, dubbed the “Accountable Capitalism Act,” was shouted down by critics on left and right who concluded that it couldn’t work or wasn’t fair — without addressing Warren’s underlying point that public companies are steering their profits away from workers and almost exclusively to shareholders.

Kevin Drum of Mother Jones put his finger on this phenomenon. He called it the “hack gap.” Democrats can’t keep from picking apart every policy proposal, no matter how theoretical or symbolic, as though they’re in the final stages of a Senate committee mark-up session.

Republicans cook up outlandishly nonsensical policies, and let it rip. Presented with a proposal that manifestly wouldn’t work but could be conveniently boiled down to a soundbite, Drum observes, “Think tanks and politicians would all chime in to support this great plan. The RNC would post YouTubes. The con men would send out fundraising appeals….This is because they know it’s not policy that matters to voters, it’s hating the right people.”

Democrats can’t stomach the idea of being thought of as hacks, even for a second; Republicans proudly wear their hackdom on their sleeves. Democrats spent years refining what became the Affordable Care Act. Republicans boiled it down to “death panels” and went to town on it — but also vowed to save things like protection for people with preexisting conditions, which was a centerpiece of, yes, the Affordable Care Act.

So let’s first examine the issues Sanders and Khanna are trying to address.

“It’s quite real that we have large numbers of working people who can’t support their families on their wages and rely on public assistance programs,” says Ken Jacobs, a labor expert at UC Berkeley.

But economists question whether this means those programs are “subsidies” for employers, as Sanders would have it. To begin with, not all of these programs are created equal. Some, such as food stamps and Medicaid, are heavily aimed at nonworking households. By providing access to staples, healthcare and other benefits, “they might discourage some people from accepting a job that’s so poorly paid it’s not worth taking,” says Gary Burtless, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. That shrinks the labor pool for those low-wage jobs, in effect forcing employers to pay higher wages to fill them.

Then there are means-tested programs specifically designed for working households, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and subsidies for day care for working parents. These programs encourage people to stay in the workforce by “topping up” their income as long as they keep working, Burtless observes. That indirectly helps low-wage employers by increasing the supply of workers, putting downward pressure on pay. The effect on employers is probably marginal, but in any case it’s the workers who get the most benefit in the form of more income. The subsidy is properly viewed as chiefly for the workers, not the employers.

It’s true that the calculus around some of these programs is altered by the current Republican campaign to saddle them with work requirements.

Work requirements for childless households were added to SNAP during the Clinton administration, but they were limited, and were suspended under President Obama during the Great Recession. Medicaid has never required recipients to work to receive benefits until the rules began to get changed under President Trump.

Patient advocates generally think these are a terrible idea, since they are designed chiefly as obstacles in the way of receiving healthcare, and the vast majority of Medicaid households include working members. The Trump policy has led to absurdities such as Alabama’s proposal that would require Medicaid applicants to work at jobs that even at minimum wage would give them income that would render them ineligible for Medicaid under the state’s stringent income limits.

The important question for the U.S. economy is how best to raise worker incomes so they don’t need government assistance. Here’s where the Stop Bezos Act is flawed; as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities observes, by charging big employers like Amazon for the direct cost of their employees’ assistance, the act would give the companies an incentive to discriminate against applicants who might even look like they’d need the help — disabled persons and those with children, for instance. The measure could prompt big employers to lobby for cuts in those programs, since the cuts would translate directly into tax cuts for themselves.

The right legislative approach is to increase the minimum wage and strengthen employees’ bargaining power by removing obstacles to collective bargaining. What’s needed, Jacobs says, is “a combination of raising the minimum wage and promoting policies that make it easier for workers to join unions.”

The federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour hasn’t been raised since 2009. Its value peaked in 1968, when it was nominally $1.60; today, that wage would have a buying power of nearly $12.

Sanders’ statement announcing the Stop Bezos Act made clear that better wages, not a tax levy on Amazon, are his real goal.

“The fact is that if employers in this country simply paid workers a living wage taxpayers would save about $150 billion a year on federal assistance programs and millions of workers would be able to live in dignity and security,” Sanders said. “That is why we are proposing legislation to demand that Mr. Bezos, the Walton family of Walmart and other billionaires get off of welfare and start paying their workers a living wage.”

It’s not as if Jeff Bezos couldn’t find the money to give Amazon’s lowest-paid employees a raise. According to the latest calculations by Forbes, Bezos is currently worth about $160 billion. He’s been widely pilloried for an interview he gave in April asserting that he had so much wealth the only way he could think of spending it was on promoting space travel through his company Blue Origin, on which he said he planned to spend $1 billion a year.

(Amazon said its total employment reached 566,000 last year, but didn’t break out its warehouse workforce. If we assume for the purposes of argument that it employs 100,000 on those low wage jobs, Bezos could gift every one with $100,000, and it would only cost him $10 billion, and he’d still have $150 billion left over.)

The truth is that proposals like Sanders and Khanna’s serve a very clear purpose in our political system. They’re not designed to end up as the law of the land, but as prompts for debate. “These sorts of efforts serve a role in bringing these issues to the fore,” Jacobs says.

Now, if only their critics would stop focusing on the trees, and pay attention to the forest.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.