How to make L.A. housing more affordable? One vision is on Tuesday’s city ballot

- Share via

Next year, developer Jamison Properties will open an apartment building in Koreatown, adding 209 luxury residences in a city where most tenants pay rent deemed unaffordable.

But the seven-story building, boasting a “state of the art fitness center” and “Zen garden,” couldn’t be constructed under existing city rules.

It needed an exemption since it was planned for a lot zoned only for parking — a distinction city planners dismissed as “archaic” in signing off on the Wilshire Boulevard project.

In receiving that dispensation, the Los Angeles developer entered a raging debate in an increasingly expensive city undergoing a development boom.

Many tenant advocates say the wave of residential construction is too focused on serving the wealthy or upscale professionals. They are demanding that projects include affordable homes when they get the kind of exemption sought by Jamison, which declined to comment for this report.

Opponents, led by development interests, argue that the proposed regulations, however well meaning, will have the unintended consequence of reducing housing production and worsening the affordability crisis.

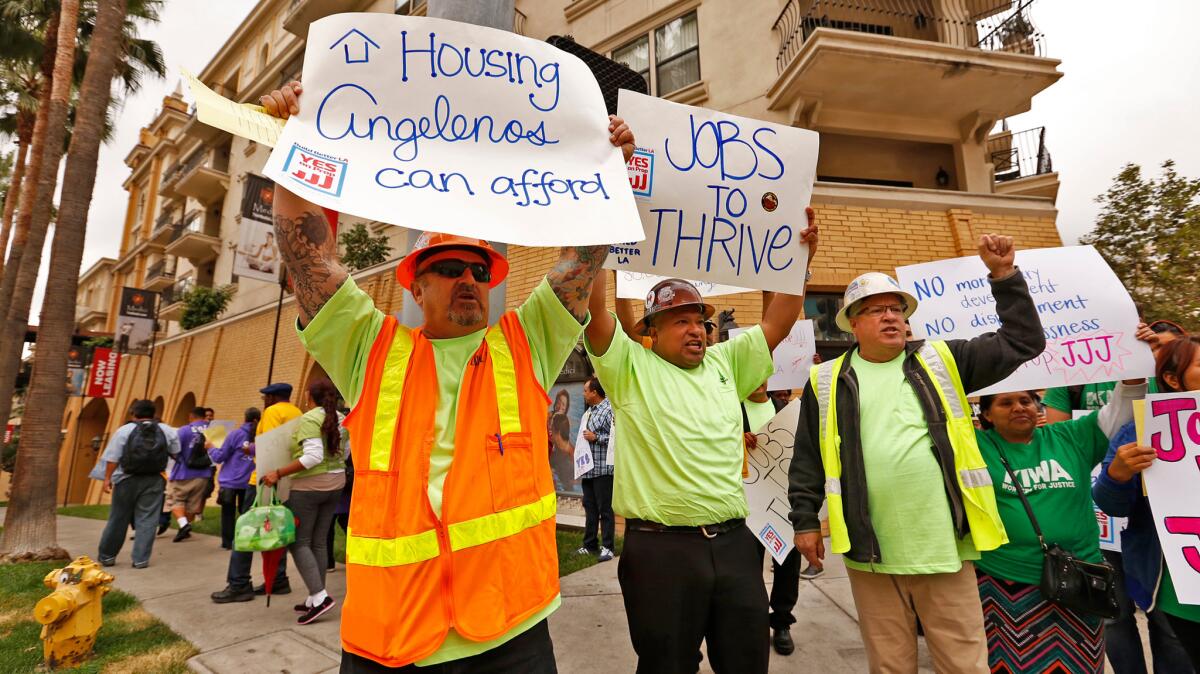

On Nov. 8, city voters will decide who they think is correct — giving a thumbs up or down on Measure JJJ, a Los Angeles initiative backed by the L.A. County Federation of Labor.

The ballot measure applies to projects with 10 units or more for which developers seek a zoning change, general plan amendment or height-district change — essentially to build more units than allowed, or to build them where they currently can’t be located, such as a parking lot or industrial neighborhood.

Those projects would need to include below-market-rate rental units, as many as 25% for apartment projects and up to 40% for houses and condos. Builders could alternatively pay into the city’s affordable-housing trust fund or build the less expensive units elsewhere. In addition, developers must pay wages set by a city agency and hire some local workers and apprenticeship program graduates

The measure differs from the more highly publicized Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, a March ballot measure that would halt projects requiring the same type of exemptions for two years as new comprehensive zoning rules are hashed out.

Labor and business are united against the March measure, but are split on JJJ, also known as Build Better L.A.

“The only way we get affordable housing is to commit to making it and requiring it,” said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival, a tenants rights organization supporting JJJ. “It’s not going to trickle down.”

The rules would apply to a minority, but significant number, of projects, according to Beacon Economics, a consultancy that studied the measure for opponents. That’s because L.A. planning rules are widely considered outdated, and many developers seek exemptions.

But that’s a practice that neighborhood groups say is bad policy, leading to City Council decisions influenced by campaign contributors.

This week, following a Times investigation, the L.A. County district attorney’s office said it would review a series of campaign contributions made by donors with ties to developer Samuel Leung, who secured changes to city planning rules for a controversial $72-million apartment complex in Harbor Gateway.

Builders, however, say that without exemptions, many projects would not be economically viable, given a series of slow-growth initiatives approved in Los Angeles that reduced the number of housing units that can be built.

“We have extreme demand and small supply and JJJ will make it harder to create any more supply,” said Ruben Gonzalez, a senior advisor with the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce.

In 1960, the city’s zoning rules allowed for enough housing for 10 million people. By 2012, zoning changes had reduced that to 4.3 million.

Meanwhile, the city’s population jumped 16%, to 4 million, between 1990 and January 2016, while the number of housing units climbed only 12%, according to state data. Many agree that imbalance is the root cause of today’s high housing costs.

“Housing units should be growing at least as fast as population and probably faster,” said Shane Phillips, a noted urban planner.

Today’s development boom appears to be having some impact, at least in the luxury end of the market and in neighborhoods awash in construction.

The median rent for all housing units in downtown Los Angeles last quarter rose 1.3% from a year earlier to $2,435 — far smaller than the double-digit percentage growth in 2015.

Citywide, rents climbed 5.5% to $2,451 in the quarter — also much slower from double-digit hikes last year, real estate firm Zillow said.

Zoning exemptions are playing a role in that.

Between 2010 and this summer, about 13% of all homes permitted in the city, or roughly 8,300 units, were in projects that received density exemptions that would be affected by JJJ, according to a Beacon analysis. Experts predict the rate to rise, because many large projects recently applied for or received such waivers.

But initiative proponents say low-income households are not benefiting enough from the construction boom, with median rents still too high and many exempted projects particularly unaffordable.

They argue the city should get tangible benefits for allowing developers to build projects with more units that earn them greater profit.

“If they are asking for something from the people of L.A., they need to give something back,” said Alexandra Suh, executive director of the Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance.

A state law already lets developers build up to 35% larger in residential areas if they include some affordable units. Anything beyond that requires the kind of exemptions JJJ targets. Other cities, including Boston, have municipal requirements for bypassing the zoning code.

But JJJ goes further and also requires that construction workers’ wages be set by a city agency. Business groups fear the rates are likely to equal wages required for public projects, which can be nearly double typical levels.

They say smaller projects that have contributed much to the housing stock are particularly vulnerable since they often don’t command the higher rent of larger ones, which often already use more expensive, union labor.

Although larger projects over the last decade contributed a greater number of residences, about half of exempted developments had between 11 and 50 units, according to Beacon.

“It just won’t pencil out,” for smaller projects, said Stuart Waldman, president of the Valley Industry and Commerce Assn. “At the end of the day a lot of folks aren’t going to be able to build.”

Al Leibovic, who builds smaller apartment buildings in the San Fernando Valley, estimates the measure would raise his construction costs as much as 25%.

If JJJ were in place, Leibovic said, he would have punted on a current project in Panorama City. There, he received a zoning change to demolish a house on Rayen Street and build 14 apartments, with one reserved for a very-low-income household.

“Anything under 25 units we would definitely not do,” he said. “Rayen,” where two bedrooms should start around $1,600, “would never get built.”

But, like much else about the contentious measure, those backing JJJ dispute housing production will fall.

“Developers will adjust to this,” said Jan Breidenbach, a housing policy professor at USC and former director of the Southern California Assn. of Non-Profit Housing. “This is not going to stop development.”

Backers also note that JJJ allows the City Council, after an economic analysis, to adjust the percentage of affordable homes the measure requires. There is far less flexibility on hiring and wage requirements.

The measure is not intended to be a permanent solution to L.A.’s broken zoning system and would expire in 10 years. By then, Mayor Eric Garcetti has pledged to update all community plans and the city’s general plan.

Rusty Hicks, executive secretary-treasurer of the county labor group, said the measure will play an important role until those plans are updated.

“The reality is those plans are not going to be crafted and redrawn overnight,” he said.

Garcetti hasn’t taken a position on JJJ, but in a statement he said he supported “the intent” of the initiative, while cautioning, however, that “deciding policy at the ballot box can result in unintended consequences.”

That’s a position supported by Raphael Bostic, an urban development professor at USC.

“These are all complex issues and you have people who are non-experts making decisions that will be long-term binding,” he said. “We wind up putting ourselves at risk of making decisions based upon who can come up with the best slogan rather than who can come up with what is right or what’s best for the city.”

Follow me @khouriandrew on Twitter

ALSO

Can heartfelt letters from the homeless convince L.A. to pass landmark bond?

Adding 1 million people along the Wilshire corridor could help L.A. create a sustainable city

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.