Martin Shkreli’s long, strange tale could end with a decade in prison

- Share via

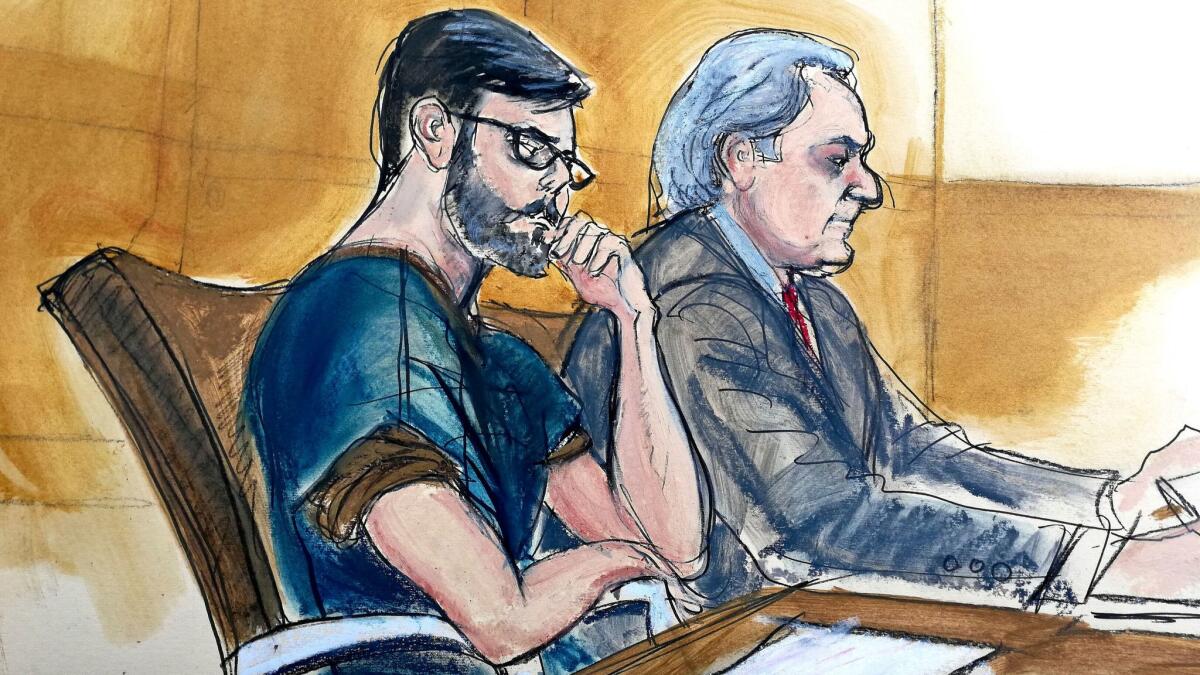

The two years since the FBI ushered Martin Shkreli, wearing a gray hoodie, out of his Manhattan apartment might as well be a lifetime ago.

The former hedge fund manager gained notoriety for his decision to raise the price of a lifesaving drug 5,000%, earning him a lecture from Congress. He smirked his way through interviews and beefed with rappers, reporters and almost anyone else in his path. He was repeatedly kicked off Twitter. There was a satirical musical about him, “Pharma Bro: An American Douchical!” (it received good reviews), and an episode of CNBC’s “American Greed” was dedicated to his antics.

On Friday, Shkreli’s unique journey from a hedge fund rising star to Wall Street bad boy will take its most serious turn yet. After being convicted last summer of defrauding investors, Shkreli faces more than a decade in prison — and his history of outrageous behavior is not likely to help his hopes for leniency.

Usually boisterous and defiant, Shkreli has suddenly struck a contrite tone. “I accept the fact that I made serious mistakes, but I still believe that I am a good person with much potential,” he said in a three-page letter to the judge overseeing his case.

It may be too late. Prosecutors argue that Shkreli, 34, should spend at least 15 years in prison. His defense team is asking for a fraction of that — 12 to 18 months — but even that would be quite a concession for Shkreli, who bragged, even after being convicted, that he would spend little to no time in prison.

“The trial and six months in a maximum-security prison [awaiting sentencing] has been a frightening wake-up call. I now understand how I need to change,” Shkreli said in his letter.

Shkreli, best known for his aggressive defense of rising the price of Daraprim — a 62-year-old drug primarily used to treat newborns and HIV patients — to $750 a pill from $13.50, was convicted last summer of lying to investors in two of his hedge funds, MSMB Capital and MSMB Healthcare, and of trying to manipulate the stock price of Retrophin, a pharmaceutical company he founded. Shkreli raised millions of dollars for MSMB Capital, but not as much as he told investors. When he made a bad bet that doomed the hedge fund, prosecutors said, he launched a scheme to cover it up, then used Retrophin cash and stock to pay off his investors.

Shkreli’s defense attorneys disputed all the charges and tried to sway the jury with a simple rebuttal: His investors were wealthy and sophisticated, and he ultimately made them richer. They are using a similar argument now that Shkreli is facing years in prison.

“How is it that someone who made millions of dollars for his investors, albeit causing these millionaires ‘frustration’ along the way, would become the target of a federal prosecution and end up before a sentencing court?” Shkreli attorney Benjamin Brafman wrote in a court filing. “There is not a shred of credible evidence in this case, nor did the jury find, that Martin was motivated by greed or by causing financial injury to his investors in connection with the three counts of conviction for securities fraud.”

To make their case, Shkreli’s attorneys submitted dozens of letters from friends, family members and former colleagues, who argued that Shkreli was not the villain he has been portrayed as. His sister, Leonara Izerne, bragged about Shkreli’s smarts in a six-page letter to U.S. District Judge Kiyo Matsumoto. “I remember that before the age of 6, he could quickly recall square roots, multiplication tables, the Periodic Table of Elements and do long division,” she said. One of Shkreli’s fellow prisoners described taking classes taught by Shkreli on business, mathematics and finance. “Prior to my arrest I attended the Pennsylvania State University studying Computer Science and Sociology, and it amazes me how I learn just as much if not more sitting in one of Martin’s classes,” Lamark Mulligan said in a handwritten letter to Matsumoto.

Prosecutors dismiss Shkreli’s contrition, calling it insincere, and say that his ability to repay investors is further evidence of his crime, not his innocence. “Not once does Shkreli acknowledge that he lied to investors and committed fraud,” prosecutors said. Shkreli’s investors were not “repaid due to Shkreli’s personal generosity or honest hard work, but … due to Shkreli’s continuing crimes.”

Even while in jail awaiting sentencing, Shkreli showed disdain for the judicial system and has been dismissive of his conviction, prosecutors said. In a January email conversation, Shkreli allegedly wrote, using an expletive, “ … the feds,” and in other exchanges he downplayed the seriousness of having to forfeit millions of dollars because of his conviction, according to court documents.

Prosecutors also pointed to Shkreli’s unusual conduct inside and outside the courtroom. During the trial, Judge Matsumoto had to order Shkreli to stop talking after he walked into a room full of reporters and called the prosecutors the “JV team.” After the trial, the judge revoked his $5-million bond after he offered Facebook followers money to pluck a strand of Hillary Clinton’s hair.

“The big risk that Shkreli faces here is that he has kind of dug his own grave four times already with this court by showing this complete disdain and thumbing of his nose to the judicial process and the court and law enforcement,” said David Chase, a former prosecutor for the Securities and Exchange Commission. “You couple that with the judge’s very powerful discretion and it just isn’t not going to end well.”

“He has a 1st Amendment right to talk, and is not shy about it, but you don’t have to exercise it and you don’t have to exercise it in the way he does,” said Chase, managing partner of an eponymous law firm. “My sense is the judge is really going to use that as a basis to hammer him.”

Shkreli has already lost two big fights. Matsumoto rejected his motion to throw out his convictions, and ruled that Shkreli must give up nearly $7.4 million in assets, including a Pablo Picasso painting and “Once Upon A Time in Shaolin,” a one-of-a-kind album by Wu-Tang Clan.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.