Despite West Coast ports’ labor deal, normality not yet on horizon

- Share via

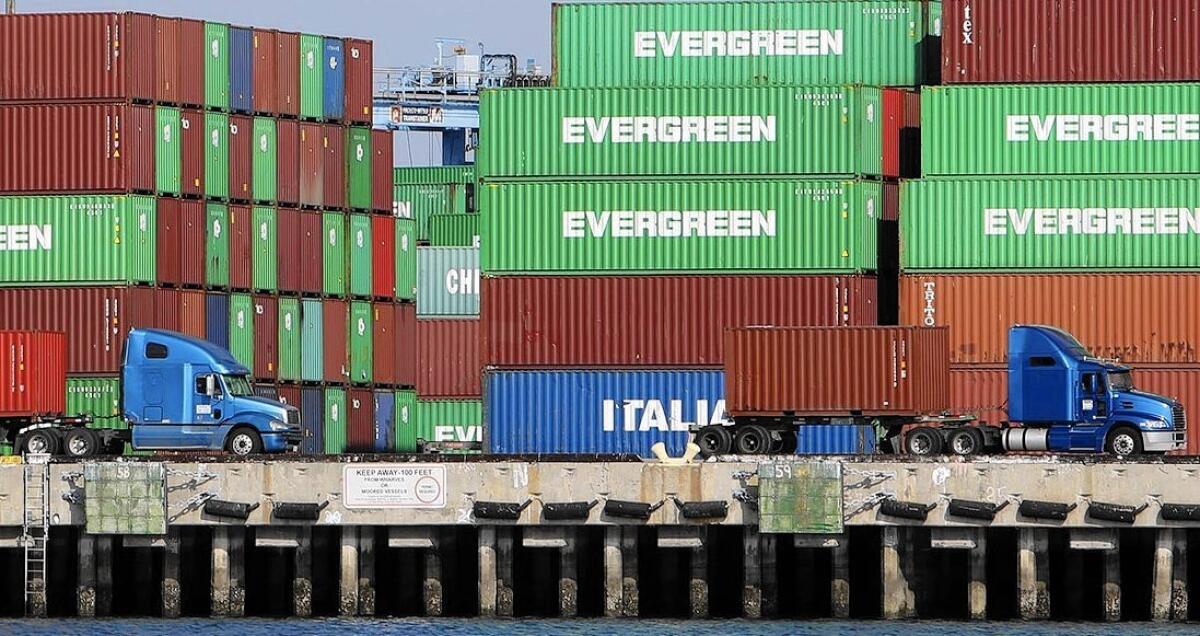

West Coast ports are emerging from the most contentious labor dispute in more than a decade, but lingering resentment and structural problems may complicate a return to normality.

Activity picked up Saturday at Western harbors after the dockworkers union and employers reached a tentative agreement late Friday on a new five-year contract that will cover 20,000 workers at 29 ports.

The resolution followed months of difficult negotiations that contributed to an extended slowdown at the docks. Cargo was stranded, disrupting operations for Central Valley citrus growers, Midwest auto factories, McDonald’s restaurants in Japan and many other businesses.

The ordeal darkened public perception of major trade portals such as the Long Beach and Los Angeles ports, which together process 40% of the nation’s incoming container cargo. Experts said that members of the Pacific Maritime Assn. — large shipping lines and port terminal operators — and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union have a hard fight ahead to win back respect and lost customers.

“I think the parties have an understanding of the impact of this disruption,” U.S. Labor Secretary Thomas E. Perez said in an interview. “They understand that they not only have to restore service, they have to restore confidence.”

Perez was dispatched by President Obama to meet with employers and the union last week and urge settlement on a new contract. A few months after the last contract expired in July, activity at the ports began to dramatically slow and each side blamed the other.

Shaming appears to have been among the tactics used to encourage a resolution.

On Wednesday, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti joined the talks and told negotiators that they were wasting time with internal squabbles as competition loomed from ports in Mexico and the opening of a widened Panama Canal due next year.

Some trade business never returned to Southern California after the employers locked out dockworkers for 10 days in 2002, Garcetti told The Times.

“If we lose those excess dollars, that is the difference for me in whether I have dollars in modernizing the port,” he said.

Garcetti said he also offered a reality check about how the standoff was affecting their industry’s reputation.

“I wanted to let them know how people view this out there in the real world. The retailers and others think you both right now are incompetent or incapable,” Garcetti recalled telling negotiators.

Craig Merrilees, a spokesman for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, acknowledged that public perception and concern for affected businesses helped the sides come to an agreement.

“The issues became narrowed to the point that it was obvious that an agreement could be had and that time was of the essence,” he said.

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach will be strong in the future “because the region has overwhelming inherent advantages that make it likely to continue being the dominant player in international logistics,” even with a widened Panama Canal, Merrilees said. Those advantages, he said, are location relative to China, a large Southern California population that needs streams of goods, strong infrastructure and political support for the ports.

Not many details are available about Friday’s agreement. The new contract still needs to be approved by individual employers and union members.

Negotiators had agreed on key issues such as healthcare and truck trailer maintenance, but reached a stalemate in the final weeks over the union’s request to change the rules for removing arbitrators, who settle disputes between shipping companies and the union over interpretations of a labor contract.

The union appeared to have a beef with a single arbitrator, David Miller, tasked with handling labor disputes at the Los Angeles and Long Beach docks. Miller told The Times last week that he was “bewildered” that union leaders wanted him removed.

Asked about Miller’s future, Perez said there would be a new selection process for arbitrators under a revamped system that employers and union leaders agreed upon.

The haggling left many outsiders feeling bitter.

“This was not a small thing. It wasn’t just that the public was displeased, it was that important segments of the public were feeling the pain,” said Harley Shaiken, a UC Berkeley professor who specializes in labor unions.

The dispute “wrought havoc” on the soybean industry, among the top agricultural exporters in the U.S., according to the American Soybean Assn. Farms, processing businesses and livestock facilities that use the legumes as feed all suffered.

“Disruptions like the one we saw out West have the potential to throw the country’s farm economy into disarray,” Wade Cowan, president of the trade group, said in a statement. “A devastating impact like that isn’t a bargaining chip.”

Small retailers in Los Angeles, such as the Well, also felt the burn. Owner Alex Weidner said the fashion store has orders for the fast-approaching spring and summer season stuck in port “with virtually no other options available than to wait.

“Clothing and fashion is definitely perishable,” Weidner said. “We only have a limited number of months to try and sell these items until they are out of season and we need to discount them on sale, which creates even more of a ripple effect throughout our business.”

Trade experts said that it could be months before ports were operating at their normal pace.

“There will be significant backlogs to clear, and everyone has a part to help restore confidence that the West Coast and the United States are open for business,” said Jay Timmons, president and chief executive of the National Assn. of Manufacturers.

Even before the union was accused of slowing operations in November, the ports had struggled with delays for months, experts said.

A truck trailer shortage and the increased reliance on massive container vessels contributed to the worst freight backlog in a decade at the San Pedro ports. At the Los Angeles port, a single ship now often carries 14,000 containers. Two years ago, a large ship would have held 8,000 to 10,000 of the steel boxes.

Many port terminals were built decades ago for much smaller ships. Container sorting procedures haven’t been updated to account for vessels carrying cargo from multiple shippers.

“There are big structural challenges that have beset the West Coast ports for a long time,” Merrilees said.

But for now, the anxiety that has shrouded the Southland seems to be lifting. For the first time since the employer group began cutting evening and late-night hours in early January, full shifts are expected to resume at the docks this weekend.

At TC’s Cocktails in San Pedro, within view of the cranes on the docks, most patrons seemed to know someone who works at the ports.

“It not only helps the community,” said retiree Mike Little, 73, “but the entire nation, because without stuff coming in, people didn’t have the raw materials to do their jobs.”

Times staff writer Chris Kirkham contributed to this report

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.