Another way the rich are different: ‘concierge-level’ fire protection

- Share via

RANCHO SANTA FE, CALIF. — Bryce Carrier’s cellphone rang at 3 a.m.: Help! The fire is almost to my house.

Carrier hopped into his heavy-duty red Ford F-550 and sped to northeast Poway, dodging fallen eucalyptus and heading straight toward the wind-whipped blaze. He arrived to find flames marching up an embankment toward the multimillion-dollar home.

Yanking out the hose in the back of his truck, he began applying Phos-Chek fire retardant along the perimeter of the property, the shrubs and the roof. When the flames hit the milky white liquid, they stopped.

Another home saved.

Carrier is a certified firefighter, but he doesn’t work for a government agency. He’s an employee of Firebreak Spray Systems, which partners with the insurance company American International Group Inc. to protect the mansions of the moneyed.

AIG’s Wildfire Protection Unit, part of its Private Client Group, is offered only to homeowners in California’s most affluent ZIP Codes -- including Malibu, Beverly Hills, Newport Beach and Menlo Park -- and a dozen Colorado resort communities. It covers about 2,000 policyholders, who pay premiums of at least $10,000 a year and own homes with a value of at least $1 million.

Carrier and his 15 crew mates sprayed retardant on and around more than 160 homes in Malibu, Lake Arrowhead and the hardest-hit areas of Orange and San Diego counties this week. They claim to have saved a dozen homes.

Jim Moore of Malibu, for one, was grateful for their services.

“Just picture it,” said Moore, whose house was sprayed by Firebreak early Monday. “Here you are in that raging wildfire. Smoke everywhere. Flames everywhere. Plumes of smoke coming up over the hills. Here’s a couple guys showing up in what looks like a firetruck who are experts trained in fighting wildfire and they’re there specifically to protect your home. . . . It was really, really comforting.”

For the insurance company, it’s also savvy business. One saved home covers the cost of the program.

“We are saving homes that may average $3 million to $5 million,” said Firebreak Chief Executive Jim Aamodt. “Those are the hard dollars, money the insurance company is not paying out.”

AIG says the service is not a replacement for public fire departments; after all, the insurer did lose some houses. But like an air bag in a car crash, the company says, it’s better than nothing.

Others say that it’s just another way for the wealthy to buy their way around cash-strapped, understaffed public services. Firefighters across the region have complained this week that they simply did not have enough trucks, helicopters and airplanes.

“What we have is a dangerous confluence of events: underfunded states, increasingly inefficient disaster response, a loss of faith in the public sphere . . . and a growing part of the economy that sees disaster as a promising new market,” said Naomi Klein, whose new book, “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism,” looks at, among other things, the response to Hurricane Katrina.

Klein said AIG offers a glimpse into the future of what she calls “disaster apartheid,” in which the affluent are better equipped for emergencies.

“You can’t fault businesses for seeing an opportunity, and you can’t fault individuals for wanting to protect their property. Pretty much anyone who could afford it would want it,” she said. “But survival shouldn’t be a luxury item.”

AIG said it did apply fire retardant to homes of some standard policyholders if they happened to be nearby, because it made financial sense. Though AIG is the only insurance company to provide emergency fire response teams, there are other fire prevention businesses that cater to the elite.

As blazes raged in Malibu this week, camera crews captured a groundskeeper at movie producer Jeffrey Katzenberg’s mansion coating the building with foam using a system installed several years ago.

Firebreak sells similar retardant systems apart from its work with AIG and says sales have tripled over last year. Installation costs about $10,000 for a device that can be activated remotely or deployed automatically when sensors detect fire approaching.

More-frugal homeowners can spend $1,000 to buy Phos-Chek, the same retardant used by the U.S. Forest Service but without the red coloring. The concentrate is mixed with water and applied with a hose.

AIG’s private fire service approach isn’t exactly new. In the 1800s, many firefighters worked for for-profit companies and would battle blazes only for those with insurance. Insurers in places including Richmond, Va., gave their clients plaques to alert crews that their homes had coverage.

AIG began its Private Client Group insurance in 2000, and it has since grown to almost $1 billion in gross premiums.

Besides specialty fire protection, in Florida AIG offers a similar service for hurricanes, dispatching pre-disaster consultants to assess shutter protection, property storage and landscaping. Home restoration teams head in after storms to help with immediate repairs, even before claims are reported, said Todd Triano, vice president of loss prevention for AIG Private Client Group.

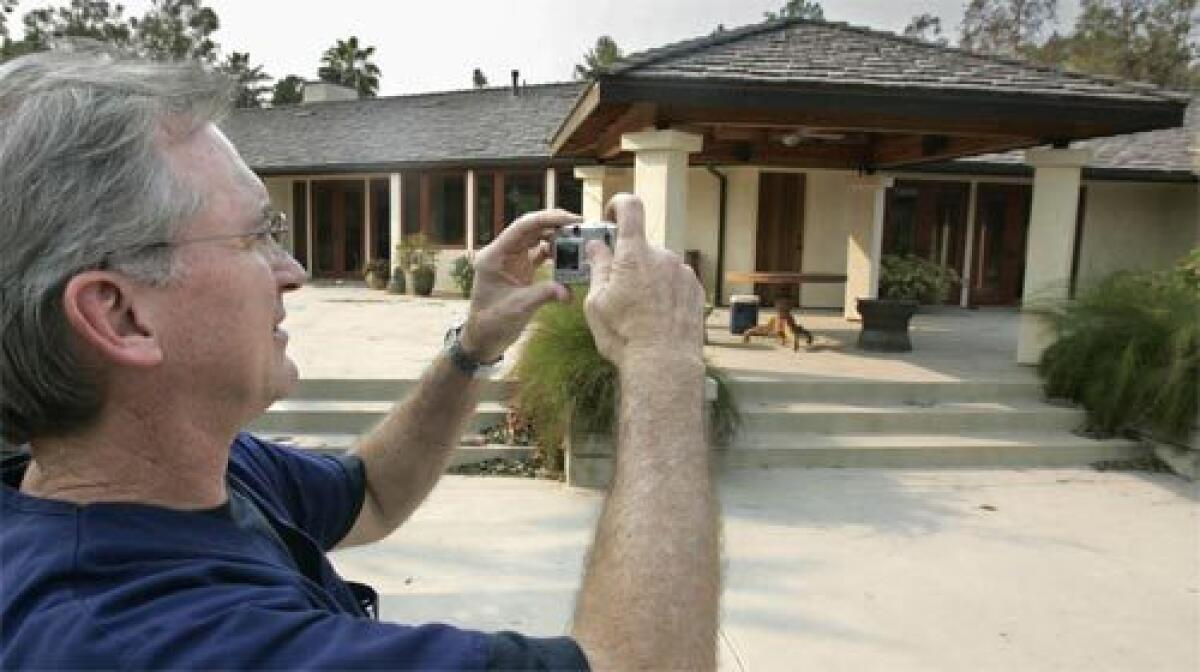

On Thursday, AIG and Firebreak teams fanned out across San Diego County, returning to homes they had sprayed to assess saves and losses. On one block of Zumaque Street in Rancho Santa Fe, with homes all around burnt to the ground, Aamodt surveyed two surviving homes bounded by blackened mountainside and singed trees.

“This is a classic use of Phos-Chek,” Aamodt said, pointing at shrubs that were half blackened and half green. “It chars at the edge of the Phos-Chek line and then it stops. . . . This is a great feeling. We’re ecstatic.”

One of the houses is owned by Kerry Roland, who returned home Thursday feeling lucky. Three houses to the south and one just north were gone.

Roland said she believed a number of factors contributed to the save, including firefighters who had put out a flare-up on her roof before AIG arrived; sprinklers she kept running; and the location of her house, on the crest of the ridge.

“When I packed up and left on Monday morning, I didn’t think our home would survive,” said Roland, 51. “It’s amazing, isn’t it? My property and the one opposite me, we both had fire retardant used.”

Local firefighters have mixed opinions about the value of services such as Firebreak.

Capt. Dan Froelich of San Diego Fire and Rescue said he was concerned what could happen if private companies sent undertrained, ill-equipped crews into fire zones and the crews got trapped and needed rescuing.

But Maurice Luque, a spokesman for San Diego Fire and Rescue, said fire retardant could be effective.

“The stuff works really well,” he said, noting that private companies are used more in eastern San Diego County.

In such places, he said, there are not many fire agencies and response times can be long. “The residents have to fend for themselves in these mountain or remote areas,” he said.

Times staff writer Tami Abdollah contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.