How Michael Bloomberg’s presidential candidacy harms journalism

- Share via

Just at the moment when presidential politics is crying out for more news coverage, not less, Michael Bloomberg’s candidacy has put the shiv into political journalism.

In an astonishing staff memo made public Sunday, Bloomberg News, the journalism arm of the billionaire’s vast business empire, said it will not conduct investigations of any of the Democratic candidates for president — that is, its boss’ rivals for the nomination — and will place other limitations on its campaign coverage.

For the record:

5:55 p.m. Nov. 25, 2019A previous version of this post said William Randolph Hearst ran for U.S. senator in 1906. He ran for New York governor that year.

That’s a bad decision, but it arises directly out of an existing, all-encompassing policy that is also journalistically dubious: Bloomberg News does not cover Michael Bloomberg, his family or his charitable foundation. In the staff memo, Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Micklethwait described this policy as “our tradition,” but that places an undeserved luster on the practice — traditions generally involve guideposts to be honored or respected, not dodges to evade uncomfortable disclosures.

Bluntly put, if Bloomberg is planning to be a serious presidential candidate, he needs to reverse this decision on coverage, depart the news business entirely, or at least put his company, Bloomberg LP, in a blind trust, enabling its reporters to cover Bloomberg the candidate without fear of reprisal from him.

Quite honestly, I don’t want the reporters I’m paying to write a bad story about me.

— Michael Bloomberg explaining in 2018 why his Bloomberg news reporters won’t report on politics if he runs for President

The memo, released soon after Michael Bloomberg formally announced his presidential candidacy Sunday via a video, observes that “no previous presidential candidate has owned a journalistic organization of this size.” Bloomberg’s news footprint in Washington is extensive — not only through its general news output, but also such specialized information services as Bloomberg National Affairs, Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Government and Bloomberg Environment.

Though Micklethwait acknowledged that this places extraordinary responsibilities on his newsroom, he tried to put the best face on the coverage policy. His memo states that the news organization “will write about virtually all aspects of this presidential contest in much the same way as we have done so far,” but it casts its current practice in oddly limited terms: describing “who is winning and who is losing,” examining policies, carrying polls, interviewing candidates.

Our emerging political debate over taxing the rich seems to be getting bogged down in details — how high a tax rate, should we tax income or wealth, etc., etc.

The memo says that “if other credible journalistic institutions publish investigative work on Mike or the other Democratic candidates,” Bloomberg News “will either publish those articles in full, or summarize them for our readers — and we will not hide them.”

But almost all of that is reactive, not proactive. It leaves many imponderables, including how aggressive Bloomberg reporters will be in interviews of candidate Bloomberg, and whether they may feel constrained to go easy on the rival candidates to maintain balance with their coverage of their boss.

The core of the Bloomberg policy is a near-complete shutdown of editorial commentary on the presidential election. Several members of the organization’s editorial board will take a leave of absence and join the campaign. The board itself is being suspended, “so there will be no unsigned editorials.” Individual columnists will continue to write, and op-eds from outsiders accepted, “although not op-eds on the election.” Obviously that punches a big hole in the analytical component of Bloomberg News.

The staff memo says that Bloomberg News will “continue to investigate the Trump administration, as the government of the day.” If Michael Bloomberg and Donald Trump end up running against each other in the general election, however, “we will reassess how we do that.”

As it happens, the Bloomberg policy raises questions about Michael Bloomberg’s relationship with his own business empire similar to those that persist about Trump and the Trump Organization. (Bloomberg News says the policy about coverage is Micklethwait’s initiative, not Michael Bloomberg’s. But he’s the boss and he hasn’t, as of this writing, disavowed it.)

Although Trump pledged to remove himself from the organization and leave it in the hands of his children once he became president, evidence is rife that he may have retained significant control and remains a beneficiary of the business. That has led to accusations that he is in violation of constitutional “emolument” clauses, which forbid the president and other government officials from receiving pay or benefits outside their official compensation.

Michael Bloomberg’s strictures about how he is covered leave open the question of his continuing control over the business enterprise he founded, through which he has amassed a fortune estimated at $54 billion. The question persisted during his three terms as mayor of New York from 2002 to 2013. Bloomberg News, a leading outlet on national and international news, was faulted for less than proactive reporting of its and its owner’s hometown.

During his first mayoral campaign Bloomberg refused to release his personal income tax returns — much as President Trump has refused to release his own. As mayor, Bloomberg allowed reporters to view redacted versions. It isn’t clear how he’ll manage the long-term expectations, flouted only by Trump, that presidential candidates reveal their taxes.

Michael Bloomberg departed the management of Bloomberg LP when he became mayor, but didn’t divest himself of the company and returned to its management after the end of his mayoral tenure. He has said he would divest the company if he became president.

Bloomberg founded his company as a specialized financial service for securities and derivatives traders; eventually it expanded into the fields of financial and national news. In 2009, he acquired BusinessWeek and added it to his news empire.

Don Blankenship on Monday announced his candidacy for president on the Constitution Party ticket.

Micklethwait’s memo points to the enduring difficulties for news organizations trying to cover their owners, especially when those owners are rich or politically active.

American history is devoid of edifying guidelines. Before Bloomberg, arguably the most politically active news tycoon (at least in front of the curtain, not behind the scenes) was William Randolph Hearst, who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1904, for New York mayor in 1905 and 1909 and New York governor in 1906.

As historian Jonathan Zimmerman recalled last year, Hearst unabashedly exploited his newspaper empire to pump up his campaigns, running headlines such as “BANK PRESIDENT TELLS WHY HE IS FOR HEARST” or “A HEARST VICTORY! CRY POLICEMEN’S WIVES.”

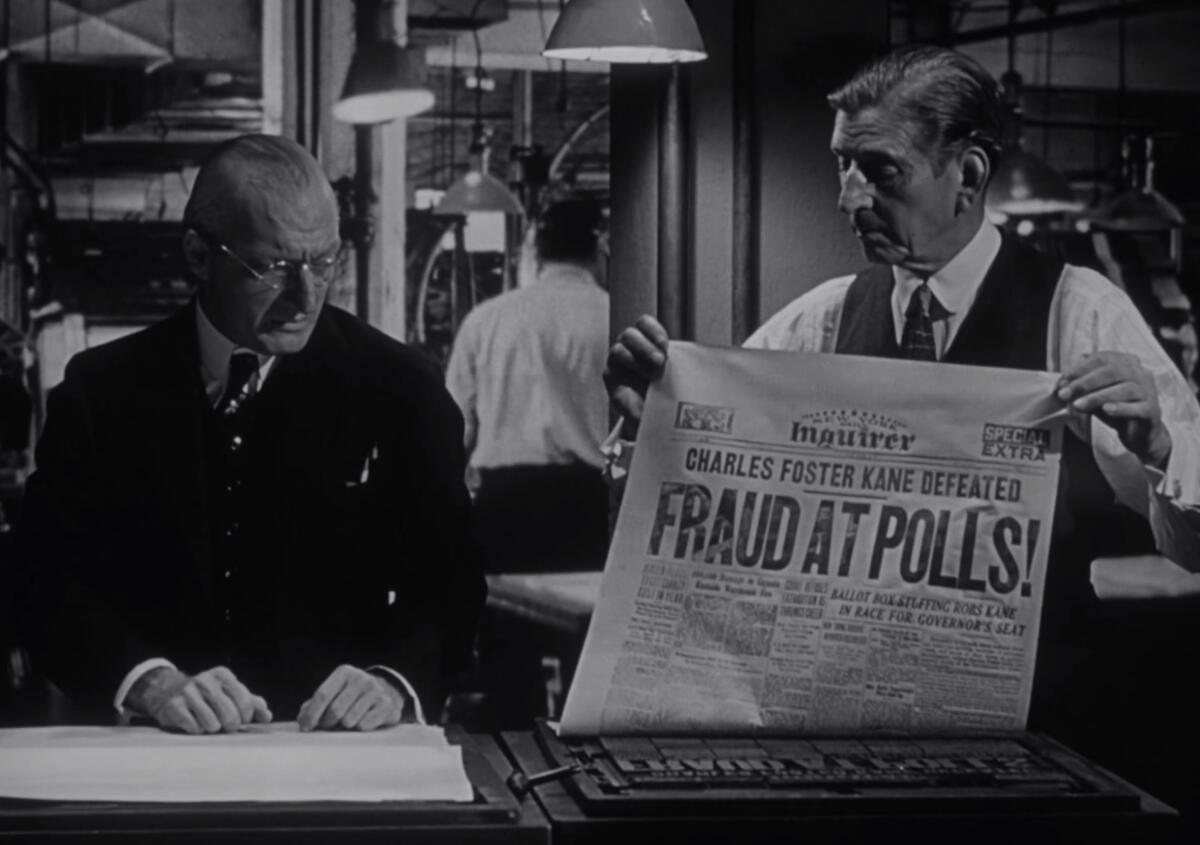

None of this yielded electoral success, as Hearst lost every one of those races. (Though he had been elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1902 and 1904.) Hearst’s record was lampooned in Orson Welles’ classic film “Citizen Kane,” which shows the title character’s deputies preparing a front-page headline attributing their boss’ electoral loss to “FRAUD AT POLLS!”

The difficulties extend beyond electoral politics. News organizations with influential owners take diverse approaches, beyond routinely reporting their owners’ interests when a news story pertaining to them breaks.

The Washington Post, which was acquired in 2013 by Jeff Bezos, the founder and chief executive of Amazon.com, hasn’t shied away from covering Bezos’ company.

Gannett and GateHouse will merge into the largest U.S. newspaper company, but its future looks anything but certain.

On Nov. 14, for example, the newspaper reported on the availability of counterfeit goods on Amazon’s sales platform and observed that the company “is failing to stanch the flow of dubious goods even with obvious examples of knockoffs.”

Nor has the Post downplayed its investigative reporting on President Trump, even though that has made Bezos and Amazon a Trump target, possibly resulting in Amazon’s loss to Microsoft in bidding for a $10-billion defense contract. (Amazon is challenging the contract award in court.)

The Wall Street Journal, which was acquired in 2007 by international news magnate Rupert Murdoch, has covered Murdoch’s overseas legal troubles extensively, though the most notable scandals, which involved alleged illegal behavior by Murdoch newspapers, were exposed by non-Murdoch news organizations and have become the topics of official proceedings that are hard to ignore.

The Times has covered investigative reports from other news organizations about the business dealings of its owner, Patrick Soon-Shiong, dating to when Soon-Shiong was a major shareholder in Tronc, then the newspaper’s parent corporation. Since Soon-Shiong became full owner of The Times and the San Diego Union-Tribune last year, The Times has covered the bankruptcy of a California hospital chain he had been involved with, and the Union-Tribute has written on other accusations pertinent to his business dealings.

MIT’s obituary of donor David H. Koch lauded him for donating to cancer research, but ignored a career undermining science.

Compared with many competitors, the approach of Bloomberg News to covering its proprietor has been remarkably hands-off. The company’s formal guidebook states, “Bloomberg Editorial doesn’t originate stories about the company.” That rule applies even to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, which doesn’t mention the company’s owner.

The candidate himself has articulated personal sensitivity to how he’s covered. “Quite honestly, I don’t want the reporters I’m paying to write a bad story about me,” Bloomberg told an Iowa radio station during an exploratory swing through that state in 2018. “I don’t want them to be independent.”

Michael Bloomberg explained to the Iowa station that “we’ve always had a policy of ‘we don’t cover ourselves’ ... I believe in my heart of hearts that you can’t be independent, and nobody’s going to believe that you’re independent.”

That’s too easy an out, and it’s contradicted in Micklethwait’s own memo, in which he says: “In journalism you ‘show’ your virtue, you don’t ‘tell’ it. You prove your independence by what you write and broadcast, rather than by proclaiming the details in advance.”

The rules laid down by Bloomberg’s editor-in-chief suggest that the enterprise doesn’t trust its own reporters and editors, who are some of the best in the business, to show their independence. The policy takes one of the nation’s largest news-gathering operations functionally out of the business of covering politics during what may be the most important presidential election in a century.

In declaring his candidacy Sunday, Michael Bloomberg presented himself as something of a savior of American democracy, the indispensable man. But his campaign began with the undermining of one of democracy’s indispensable pillars.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.