Tom Steyer’s proposed congressional term limits are a lousy idea

- Share via

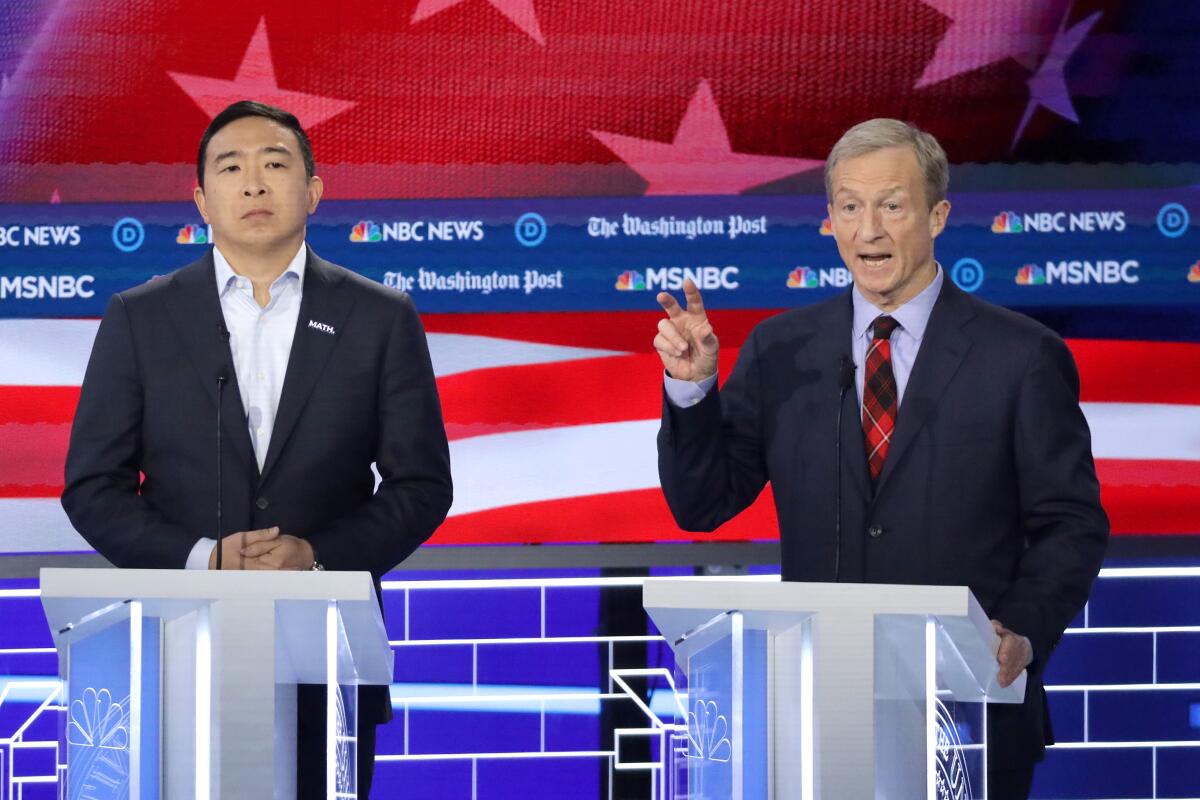

Primary debates are perfect forums for tossing out ideas that offer no virtues except that they’re instantly crowd-pleasing. Sure enough, presidential candidate Tom Steyer aired out one of these at Wednesday’s Democratic debate: term limits for members of Congress.

“I’m the only person on this stage who will talk about term limits,” Steyer said. To which we might add: Thank goodness.

I can see no propriety in precluding ourselves from the services of any man, who ... shall be deemed universally, most capable of serving the public.

— George Washington, speaking against term limits in 1788

Calls for term limits are perfectly designed to appeal to voters’ primal reflexes, the ones that arise from what evolutionary psychologists sometimes call the “lizard brain.” They’re the legislative reduction of the impulse to “throw the bums out,” that all-purpose solution for disaffection with politics.

The chief problem with term limits is that there’s no evidence that they improve political leadership and plenty of evidence that they hobble good governance. Paired with what Steyer calls “direct democracy” — another notion he offered from the debate stage — they’re more likely than not to be disastrous.

For a good example, look no further than California. More on that in a moment.

Steyer, an investment billionaire currently occupying a fringe position in the large Democratic field, didn’t have a chance to provide much detail about his ideas. But they’re both part of his published platform for “structural reform” of the government: He would place a limit of 12 years of service on Capitol Hill, combining House and Senate terms, and institute a national referendum process for up to two issues per year.

Could a reassessment of Proposition 13 finally be in the wings?

Ever the idealist, he says: “This process would increase voter participation, thwart congressional gridlock and give the American people more power over their democracy.”

Both “reforms” indisputably would require a constitutional amendment; the Supreme Court made that clear on term limits in 1995, when it trashed an attempt by Arkansas to limit its elected representatives to three terms in the House or two in the Senate.

(The court found that the Constitution’s specifications — that a representative be at least 25 years old and a citizen for seven years, and a senator be at least 30 and a citizen for nine years, and that on election day both be inhabitants of the states electing them — were the only applicable job requirements.)

Proponents of congressional term limits typically point to the presidential term limit, enacted via the 22nd amendment, as a model. The history of the 22nd amendment however, speaks more to its partisan origins than its wisdom. The amendment was enacted by a newly Republican Congress in 1947 as a direct repudiation of the Roosevelt administration; it might be seen as the first blow in the GOP’s war on the New Deal, which persists to this day. The measure was ratified in 1951.

Supporters often argue that a presidential limit to two terms was endorsed by George Washington, but that’s incorrect. Washington specifically disdained the idea, in a 1788 letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, writing: “I can see no propriety in precluding ourselves from the services of any man, who ... shall be deemed universally, most capable of serving the public.”

That brings us to the consequences of term limits. As the experience of California and other states have shown, they tend to deprofessionalize the legislature. As a result, they increase the power of the governor, legislative staff and, most disturbingly, lobbyists for special interests.

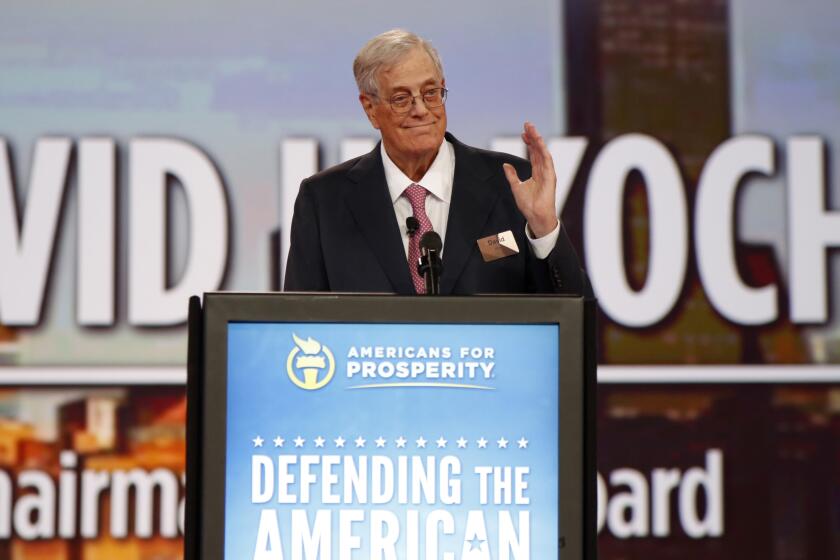

David Koch leaves a raft of right-wing policies behind him, but his real innovation was creating a dark money network.

Because they don’t face term limits, staff members and lobbyists have an interest in making themselves most knowledgeable about legislative issues. Knowledge is power, of course, and their comparative authority gives them more scope to browbeat overmatched legislators.

Legislatures everywhere, from Congress down to the lowliest part-time state legislature, comprise both talented and thoughtful members and time-wasters. Term limits are equal-opportunity ejection seats, depriving voters of the essential ability to exercise their discretion.

In California, as at the federal level, the legislative term limit enacted in 1990 was a partisan measure masquerading as government reform. It was manifestly aimed at then-Assembly Speaker Willie Brown (D-San Francisco), who by 1990 had served 26 years in the Assembly and 10 as speaker. Republicans knew they had no chance of dislodging the immensely popular Brown from his seat in an election, so they staged an end-run under a successful disguise.

As it happens, the measure limiting Assembly members to three two-year terms and senators to two four-year terms in a lifetime, had to be amended in 2012 for greater flexibility. The rule now allows for 12 years total of service in the Legislature divided between the chambers in any pattern.

The measure’s fans sometimes point to the greater numbers of women and minorities in the Legislature as a positive harvest of term limits, but that’s questionable. The Legislature’s greater diversity is almost certainly a consequence of the growing power in Sacramento of Democrats, something that is itself the harvest of the electorate’s growing diversity and the utter inability, or disinclination, of the state’s Republicans to make their policies palatable to voters — dating back to Republican support of the anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in 1994.

The $6-billion California stem cell program, created at the ballot box in 2004, is about to notch a major achievement.

Term limits have only contributed to public disaffection with Sacramento. Term-limited Assembly members and senators have less incentive to forge long-term relationships with their constituents — why bother if you’re going to be automatically turfed out long before you can turn legislating into a career? That in turn has arguably prompted more interest in ballot initiatives, the roster of which seems to grow longer every election cycle.

Ballot measures, however, have long since established themselves as playthings of special interests. The prototypical example is Proposition 13, the 1978 measure capping property taxes. This was pitched as a savior of residential property owners facing rising taxes, but it was really a Trojan horse devised by apartment owners and the commercial real estate industry. Those interests have reaped the greatest benefits from Proposition 13, which is why a measure to bring taxes on business properties more into line with residential taxes will be on the November 2020 ballot.

It’s not unusual for ballot measures to win the approval of voters despite provisions that work directly against voters’ interests. That includes Proposition 71 of 2004, which created California’s $6-billion stem cell program.

Proposition 71 was sold to voters as a gateway to cures for a host of intractable diseases, a promise hopelessly incompatible with the way science is done. Its promoters also tried to make a virtue out of its nearly total independence from legislative oversight, another artifact of anti-government sentiment. The stem cell program has indisputably supported excellent science, but its lack of legislative oversight remains a flaw.

Steyer should look to the record of California, his home state, in wrestling with the drawbacks of term limits and “direct democracy.” Both notions look good on paper and sound even better when dispensed from the debate stage. But they won’t improve voters’ access to good government — they’ll diminish it.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.