The profound costs of global learning loss, and what can be done about it

- Share via

This is the March 14, 2022, edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

Since the start of the pandemic, educators and scholars have been ringing the alarm about learning loss and the long-term effects it will have on students and society at large. But as we contemplate this issue — one so colossal that it is difficult to fully grasp — many of us are probably not considering the education that’s been lost worldwide, and what that has to do with us.

Nearly 1.6 billion learners across the globe endured school closures that lasted from a few months to two years, and the consequences of these learning gaps will reverberate for generations, according to a recent report from the World Bank, UNESCO and UNICEF. Students now risk losing $17 trillion in lifetime earnings, or about 14% of today’s global GDP, because of COVID-19-related school closures and economic shocks.

I spoke with Robert Jenkins, director of education and adolescent development at UNICEF and author of the report, about how the learning crisis will make it harder for students to thrive now and later in life — and why that poses a major threat to the health of our global community — unless drastic steps are taken to address it. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

8 to 3: We’ll start with a big question. How exactly has the pandemic worsened inequality in education internationally?

Robert Jenkins: The full scale of the learning loss and other related impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has had on education is still emerging. But as data is coming in from various countries around the world, it is very concerning and shocking. To give you a couple of key statistics: in low- and middle-income countries before the pandemic, about 53% of children could not read or understand a simple text at 10 years old. That’s now gone up to 70% two years after school closures began.

The world was experiencing a global learning crisis before the pandemic. So this is really a crisis upon a crisis. In Ethiopia, primary school children were estimated to have learned between 30% or 40% less in the subject of math than they would have learned in a normal school year. In several Brazilian states, about three-quarters of children in Grade 2 are off track in reading. In South Africa, we have schoolchildren that are close to a full school year behind.

It’s important for us to recognize the truly disproportional impact the pandemic has had on the education systems of children living in poor communities or poor families, and children with disabilities.

8 to 3: People have a tendency to focus mostly on the education outcomes of their own children, and they may not be thinking about the implications of international learning loss. Why should an average U.S. citizen care about this?

RJ: Schools have always been more than a place of learning. Learning loss is obviously very concerning and something we’re working hard to address, but the closing of schools also had an impact on children’s well-being because they no longer had access to other services that schools provide. In poor countries, a midday meal at school is of critical importance, but so is access to healthcare, immunization, water and sanitation — as well as a sense of safety and a chance to interact with peers and with other adults.

Schools can really provide a safety net for children, particularly marginalized children. Children were cut off from that full support system, leaving them with that immediate impact as they no longer had access to those services, but also it came with increased risk of exploitation and abuse. For example, it’s estimated there’ll be an additional 10 million child marriages that may occur now until the end of the decade as a result of the pandemic. There have been increased levels of gender-based violence. More and more students, predominantly boys, are dropping out of school and entering the labor market.

Children who are not benefiting from a holistic school system that enables them to be successful will not be realizing their full potential and therefore will not be contributing to their families, their communities and their country to their maximum ability. And that will obviously then constrain economic development, social development, etc. With growing inequalities, we have a growing risk of increased social tensions. It will be harder for young adults to successfully transition to employment. This will impact global economics profoundly — hence the need for leaders beyond education to do all they can to invest in effective recovery programs.

8 to 3: The report notes that past crises, like the 2005 Pakistan earthquake, show that learning losses may grow even after kids come back to school. One way to prevent this is by implementing “learning recovery programs.” What are those and how do they work?

RJ: This is another reason why disadvantaged children are disproportionately impacted. Now, after their schools have been closed, they’re coming back to schools that tend to be more likely not to have the full range of services that they need in order to recover and accelerate. As children return into the classroom, it’s absolutely critical their learning levels are assessed and that teachers have the tools and support to enable each child to catch up and get back on track.

Think of a girl in India who, when the pandemic first hit and schools closed, was in Year 6 for studies. Now she’s supposed to be in Year 8, and she’s expected to manage and learn at that level. But for the school to bridge her to Grade 8, they need to measure her learning level and how to accelerate that. In many school systems, teachers don’t have the tools or the capacity to have this kind of catch-up program. So as the curriculum becomes more demanding, children will fall farther and farther behind, making it more likely that they’ll drop out. We are very, very concerned about high levels of dropout because gaps of learning are just too great to overcome.

So learning recovery programs first assess where kids are, and then simplify key learning outcomes from the curriculum so that children can hit those milestones. It’s really targeted, accelerated learning so that children can meet those standards of the grade they’re supposed to be in. But for a child to catch up in their learning and be successful, it’s more important than ever that they receive not only the technical elements of the recovery program but broad, comprehensive support — like mental health and nutrition — tailored to their individual needs.

8 to 3: You make the point that while evidence of lost gains in reading has been documented in many countries, more robust data on learning loss is still pretty scarce. Why should education leaders prioritize tracking this kind of data?

RJ: The first people to use data are teachers and parents and children themselves to guide their own learning. But when data is aggregated at the national level, it enables leaders to steer the broader ship on what additional support is required and how to adjust the curriculum to enable children to catch up. Data that shows the evidence of losses in reading and math can enable more effective advocacy, planning, and allocation of resources so that marginalized areas and schools that are falling behind would be prioritized. It should be an all-hands-on-deck governmental, society-wide effort to track this information and do something about it.

8 to 3: Let’s end on a positive note — what are some educational innovations and positive shifts that have come from the pandemic?

RJ: When schools closed, we employed a whole wide range of different technologies and worked very closely with governments, the private sector and communities to enable children to learn remotely. There have been some really cutting-edge examples of using artificial intelligence, big data and machine learning to give teachers state-of-the-art digital support.

We also have learning tools that are particularly designed to reach disadvantaged students, such as children living with disabilities. These are tools that make learning materials more accessible, including digital textbooks. We’re seeing that now in Kenya, and it’s showing great promise.

As we emerge from the pandemic, we’re seeing that school systems that invested earlier in dynamic approaches and provided a wide range of ways kids can learn are faring better. An example of that is Uruguay. Over the past 10 years, they invested significantly in improving digital infrastructure, digital content and teacher capacity. So when the pandemic struck, they were able to just very quickly shift to online schooling. One of the key lessons that we learned and we’re now putting into practice is the need for dynamic, resilient education systems that leverage the best in class across a wide range of technologies and innovations.

:::

LAUSD hit by declining enrollment, teaching about Ukraine, and more

Some Los Angeles schools are facing uncertain futures as student enrollment declines dramatically, reports my colleague Melissa Gomez. L.A. Unified’s predicament reflects a reality experienced in districts across California: far fewer students are on the attendance rolls as a result of falling birthrates, out-of-state migration, the high cost of living and the growth of charter schools.

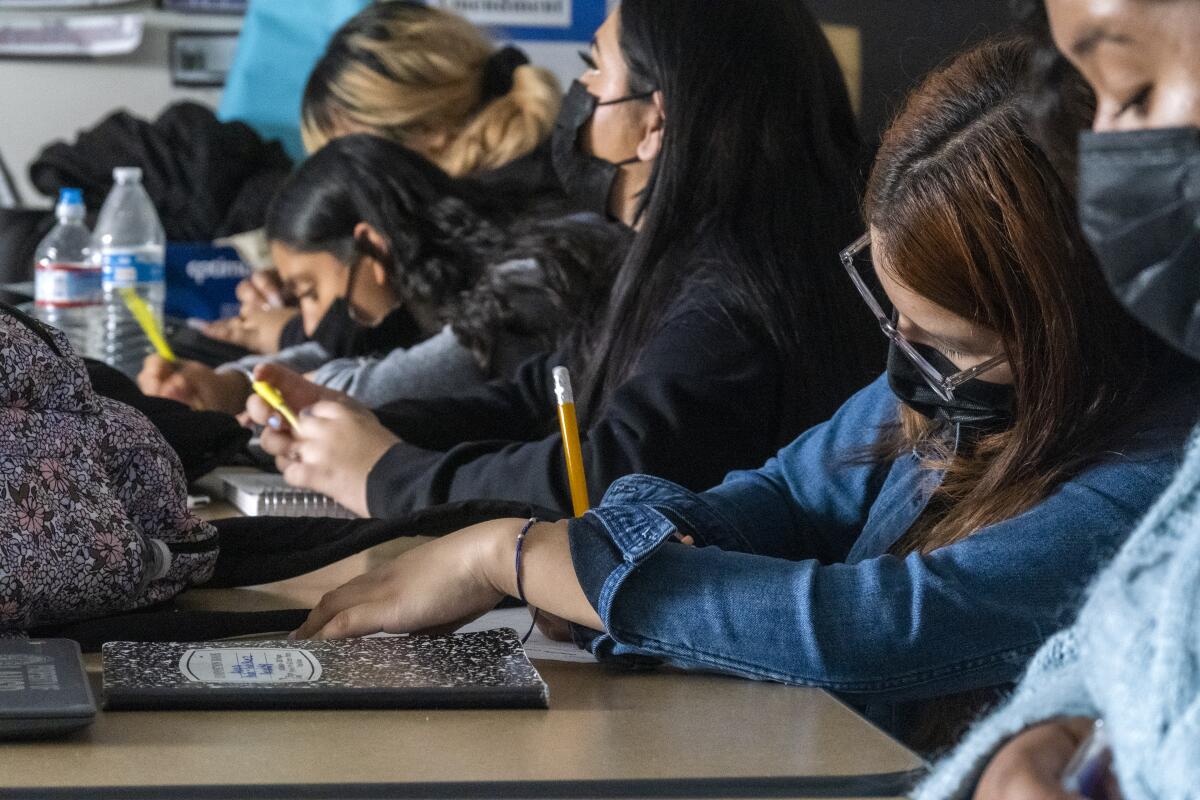

As the news of Russia invading Ukraine dominates news cycles, teachers throughout the country are helping students navigate the wave of emotions that comes with devastating world events. They’re providing much needed historical and political context. And they are doubling down on media literacy practices amid the flood of misinformation online. Melissa Gomez sat in on one of these lessons at an L.A. high school earlier this month.

UC Berkeley and city and nonprofit collaborators unveiled plans last week to provide interim housing at a converted motel, as well as meals and social services, to unhoused people sleeping in the iconic People’s Park. The announcement is a major milestone in the four-year journey to repurpose the park — one of California’s most contested pieces of land with a half-century history of protests and conflict — into space for badly needed housing for students and low-income community members, according to Times writer Teresa Watanabe.

California State University has paid more than $4 million in salary and benefits to a small group of former executives as part of a program to help with the “transition” after they step down from their posts, according to state records and interviews by The Times. As part of the deals, former executives are entitled to full medical, vacation and other benefits and their salaries accrue toward their pensions. The payouts were made at a time when undergraduate tuition increased by 5%.

If you’re a student, we want to hear about your experiences of seeking out and receiving mental health support on your campus. This is part of our ongoing coverage of the youth mental health crisis. If you’re interested in sharing your story, tell us more here.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

What else we’re reading this week

New studies show that about a third of children in the youngest grades are missing reading benchmarks, up significantly from before the pandemic. Children across demographics have been affected, but Black and Latinx children, those from low-income families, those with disabilities and those who are not fluent in English have fallen the furthest behind. New York Times

Black families in San Francisco Unified School District have often felt unheard. Will the district’s new school board members finally listen? San Francisco Chronicle

Teachers across the United States continue to lead complex history lessons on race and slavery, even though 41 states have moved to limit discussions about whether the United States has a racist history. USA Today

Teachers have been working longer hours. They’re more stressed out. And many say they’ve considered quitting. Yet the great majority of teachers decided to stay in the profession throughout the pandemic, according to a robust Chalkbeat analysis.

What happens when an elite public school becomes open to all? After a legendarily competitive high school in San Francisco dropped selective admissions, new challenges — and new opportunities — arose. The New Yorker

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

In this pivotal election year, we’re launching a new newsletter. The focus: Los Angeles politics and the people who run this town. With deep dives and insider tidbits, we’ll let you know what matters and why.

Sign up for L.A. on the Record.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.