In mental health support for others, a death row inmate finds his purpose

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Thursday, Dec. 14. I’m Thomas Curwen, a reporter specializing in long-form narratives. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- A death row inmate finds purpose in providing mental health support

- House Republicans vote for Biden impeachment inquiry

- Send a letter to the dead at this P.O. Box in L.A. (they might actually receive it)

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A death row inmate finds purpose in providing mental health support

I first met Craigen Armstrong last year during a tour of his floor in the Twin Towers Correctional Facility. I had never been inside the jail, which looms on the outskirts of downtown Los Angeles like a modern medieval fortress.

Sheriff deputies took me through a labyrinth of stairs, corridors and elevators to Module 141, where Armstrong was waiting.

We chatted a bit about a program that he and a fellow inmate, Adrian Berumen, helped develop for mentally ill inmates. Berumen had left for prison a few months earlier, and Armstrong was eager to talk about what they had accomplished.

Much is said about the mental health crisis in America‘s streets and jails. Politicians promise action, but action seems elusive.

Armstrong and Berumen’s work, however, suggests that the crisis is not entirely unsolvable. Their program succeeds on the merits of its simplicity and the radical thought that if people with mental illness are treated with kindness and encouragement, they can get better.

After the tour, Armstrong agreed to share the story of not just this program but also his journey as an incarcerated man, trying to bring meaning and purpose — if not redemption — to his life.

Convicted of the murder of three brothers in Inglewood in 2001, he spent 12 years on death row in San Quentin before the state Supreme Court reversed the judgment after his appeal and returned the case to the Superior Court. Still charged, he waits in jail.

I first heard about the mental health assistants program — as it is called — while working on a story last year about a young man with schizophrenia who was held at Twin Towers.

Armstrong and the young man never crossed paths, but I wish they had. The mental health assistants program brings inmates from the general population into Twin Towers, where they live with inmates with mental illness and help them manage their medications, hygiene and social skills.

The work is demanding. Each assistant is responsible for up to two dozen inmates and must practice patience and empathy in the presence of paranoia, hallucinations, depression and other symptoms of mental illness. I wondered where that capability came from among those whose time in jail probably required the exact opposite skills.

Having spent more than half of his life incarcerated, Armstrong understood the question.

“This is a system that disincentivizes empathy,” he told me. “In jail, we’re thinking about ourselves in order to survive. So it is hard to think about others.”

He acknowledged initially being overwhelmed by the irrationality, randomness and volatility of many of the inmates, but then he realized how much they have in common.

“All of us are a life event away from mental illness,” he said. “That is how fragile the mind is — how delicate it is — and if you don’t have protective barriers — spiritual things to help you cope — you will become mentally ill, have nervous breakdowns, depression to the point that you are never the same again.”

Over the course of reporting this story — four visits to Twin Towers and a series of phone interviews with Armstrong — I was struck by the scale of his achievement. Inmates were living in an environment that reflected their humanity. They were engaged with one another and committed to a routine that kept them safe and healthy.

I also came to appreciate what Armstrong had overcome. His life will forever be caught up in a terrible cycle of events that played out over two nights in Inglewood 23 years ago — events that tragically will not surprise anyone familiar with neighborhoods in Los Angeles caught up in gang violence.

(At his trial, an expert from the Inglewood Police Department testified that 50 gangs operated in Inglewood, most affiliated with the Bloods. In 2001, the year he was arrested, there were 25 gang-related homicides in Inglewood, according to The Times.)

Incarcerated at age 20, Armstrong was a young man driven by impulse and fear, trying to figure out how to survive. When anger failed, he turned to education and the hope that he might be able to prove his value to a society that wanted to cast him aside.

After his appeal in 2016, he returned Los Angeles and was lucky to meet Berumen, whose life had followed a similar course and who was just as eager to prove to the world that one moment in his life didn’t define who he was.

Jail in Los Angeles County is a bleak place. Inmates live in abject conditions with the constant threat of violence. Opportunity is limited, but against all odds, these two men found it and are now trying to share it with others.

Today’s top stories

Politics

- House Republicans voted to formalize an impeachment inquiry against Joe Biden.

- Donald Trump’s election interference case in Washington will be put on hold while the former president further pursues his claims that he is immune from prosecution, a judge ruled.

- Hunter Biden refused to sit for closed-door questioning by Republican lawmakers investigating his business dealings and said that he would only testify in a public hearing.

- Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis bragged about a COVID study during Gov. Gavin Newsom debate. Not so fast, lead author says.

- California is losing clout in the U.S. Capitol.

Local politics

- The Los Angeles City Council voted to allow large-scale digital signs on the city-owned Convention Center in downtown L.A.

- Since their 2022 election, a conservative majority on the Huntington Beach City Council has pursued Pride flag bans, book bans and voter ID requirements. Some residents wonder what all that has to do with running a city.

Housing and homelessness

- Southern California home prices dipped from October to November, the first decline in nine months.

- Can homelessness in L.A. ever be ‘rare, brief and nonrecurring’?

War in the Middle East

- As a protest calling for a cease-fire in the Gaza Strip blocked southbound traffic on the 110 Freeway in downtown Los Angeles, video footage showed angry motorists skirmishing with demonstrators.

- Faculty and students across the University of California are demanding that Board of Regents Chair Rich Leib resign, blasting ‘one-sided’ social media action they say dehumanize Palestinians.

- After Hamas’ attack, the U.S. pledged full support for Israel. Now, as more Palestinians die in Gaza, President Biden tries to rein in Prime Minister Netanyahu.

- Even before the Gaza war, antisemitism was on the rise. That has deeply unsettled many American Jews, accustomed to seeing the U.S. as a safe haven.

Business

- OnlyFans made them rich quick. So how do these three creators — aspiring actors, models and entrepreneurs — spend the money they make?

- Businesses pay thousands of dollars to be certified as B Corps, to signify they are “forces for good.” Celebrity-backed brands have also embraced the cause. But some in the B Corps ranks have doubts about the certification process.

More big stories

- In the wake of multiple lawsuits filed against him, former members of Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ inner circle told The Times that his alleged misconduct against women goes back decades.

- Doctors and dentists at L.A. County-run facilities plan to go on strike after Christmas.

- Want a Shohei Ohtani Dodgers jersey? They’re selling faster than Messi and Ronaldo jerseys.

- California State University was rocked by sexual misconduct scandals. Its most powerful leaders were not held accountable.

- The NFL is coming back to SoFi Stadium for another Super Bowl at the end of the 2026-27 season.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Editorial: Trump wants to be the U.S.’ first dictator.

- Mary McNamara: ‘The Crown’ was Netflix’s crown jewel. Then it pushed Queen Elizabeth II aside.

- Opinion: Almost two years into the Ukraine war, are sanctions against Russia actually working?

Today’s great reads

We interviewed Elon Musk’s groveling new chatbot about its boss: ‘He’s the king of Twitter.’ The Times sat down — or logged in, rather — to interview Grok, Elon Musk’s new AI chatbot, about the billionaire tech mogul and his various controversies.

Other great reads

- If you want to send a letter to the dead with the chance that they’ll actually receive it, there’s a box at a Los Angeles post office that carries a mysterious power.

- You’re not gross and sad for getting older. Here’s how to think about aging instead.

- Actor Danny Trejo says it’s the best time in history to be sober.

- Parrillas, cola de mono and Día de las Velitas. Learn about Latin American holiday traditions.

- Making tamales brings my family together. But can we keep the tradition going?

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 🦞A restored 1940s Texaco gas station is serving plump Maine-caught lobster rolls and lobster salads in Koreatown.

- 🍴Michelin adds seven restaurants to its California guide — and three of them are in L.A.

- 🎭 Netflix is a Joke 2024 announces lineup with Ali Wong, Chris Rock, David Letterman and more.

Staying in

- 📺 Where to stream 6 essential TV shows and movies from actor Andre Braugher, who died Monday at 61.

- 🍹 Here’s a recipe for coconut-pina-guava fresca, a nonalcoholic cocktail from Danny Trejo’s new book, “Trejo’s Cantina.”

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... from our archives

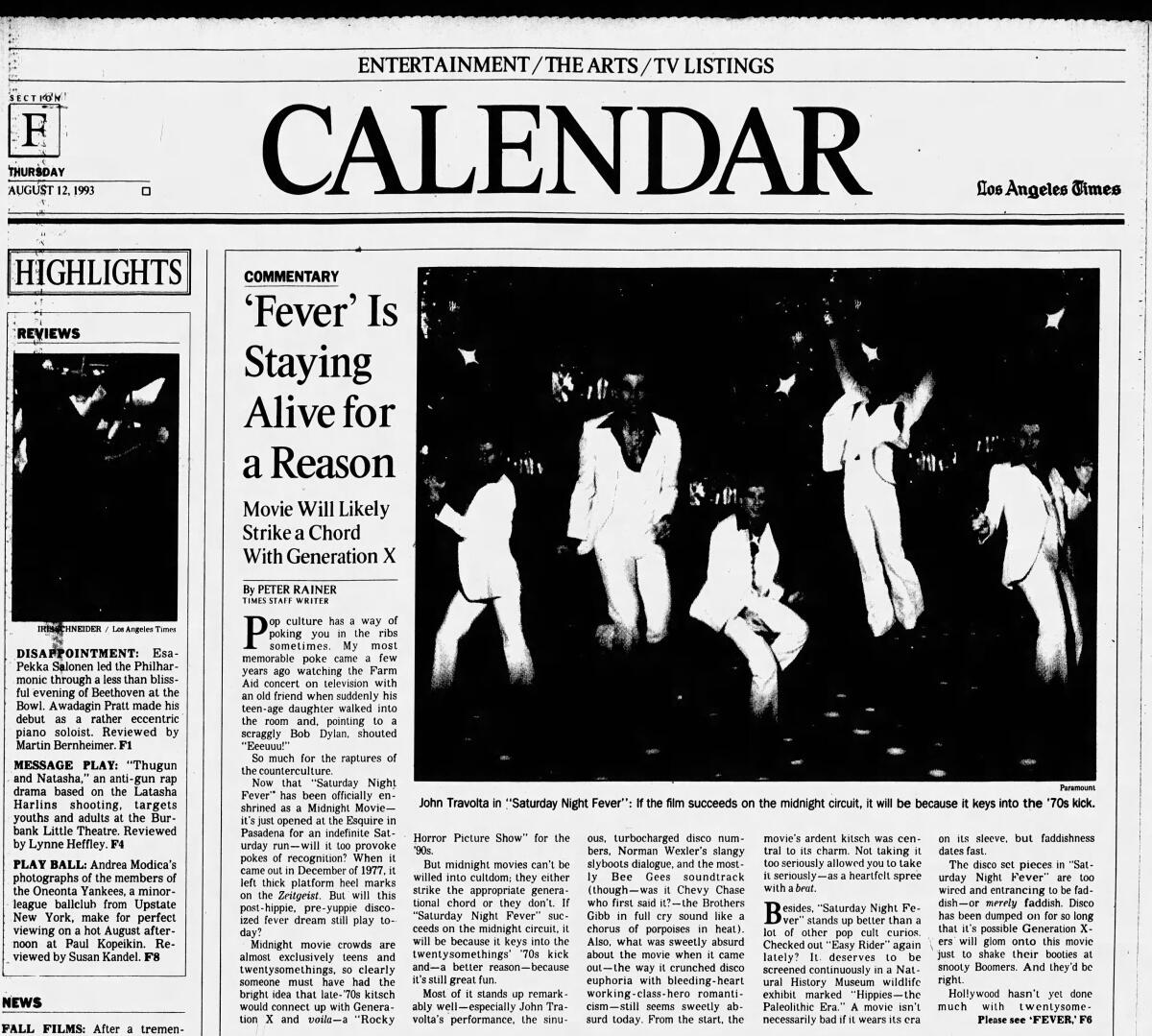

On Dec. 14, 1977, “Saturday Night Fever” premiered in Los Angeles at Mann’s Chinese Theater, catapulting then-23-year-old John Travolta to superstardom and his first Oscar nomination for best actor. Sixteen years after the film’s premiere, The Times’ Peter Rainer wrote about it attracting midnight movie crowds and striking a chord with Generation X.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Thomas Curwen, long-form narratives reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Laura Blasey, assistant editor

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.