Let’s shift stalled bullet train funds to L.A. and San Francisco, where they’ll do some good

- Share via

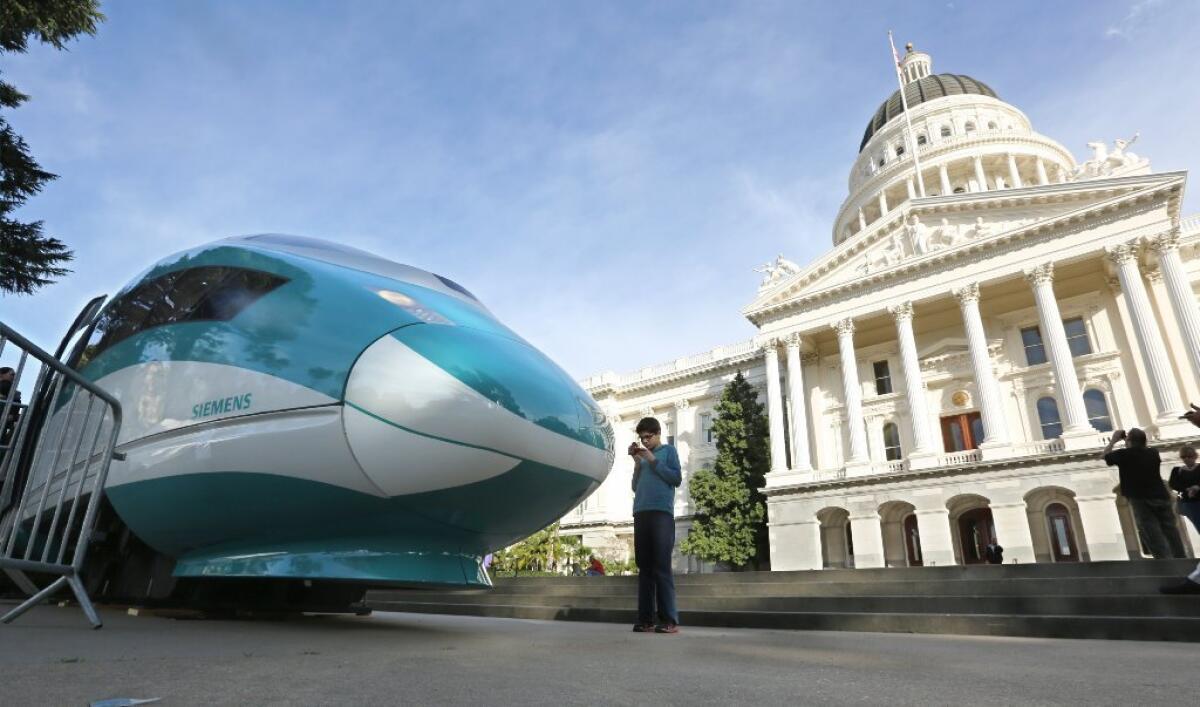

Is now the time to switch tracks?

I’m talking about the long-troubled California bullet train, which can’t seem to get out of the station.

My apologies to Fresno, Modesto, Stockton and the rest of the Central Valley. But this plan to keep building there despite little problems like lawsuits, mismanagement, epic delays and the fact that nobody has any idea how to pay for a project which may or may not ever be completed, makes less sense each day.

So count me as a supporter of the plan by several legislators to scale back on the Central Valley portion and shift funds to the bookends on the drawing board — Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area. In those teeming, congested regions, bolstering existing rail systems could do some good in the very near future.

“I think the whole thing is a bit of a mess right now,” said Assemblywoman Laura Friedman of Glendale. “We need to pause and think about what we’re doing, and proceed in a way that makes the most sense for the whole state.”

Back in the early days of the dream, it was easy enough to argue that what made the most sense for the state was to join the can-do spirit of other world leaders and lay track that would have us barreling from L.A. to S.F. in less than half the time it takes to drive, and at a fraction of the cost of flying.

Then came the cost overruns and epic delays and myriad other problems, and the great vision seemed more like a hallucination.

On Monday I read my battle-tested colleague Ralph Vartabedian’s latest chapter on the continuing saga of the little engine that can’t, and I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Did you see this?

The High-Speed Rail Authority’s administrative staff, despite a million unanswered questions and a raging divide over how to proceed, is barreling ahead with plans to lock itself into a 30-year contract on construction, maintenance and equipment on segments it can’t afford to build.

Vartabedian reported that rail authority chief Brian Kelly argued that moving forward will fulfill the mission to build an electrified high-speed system and that federal grant agreements give the authority no choice.

But the Federal Railroad Administration blasted the plan to proceed with the largest contract in the history of the bullet train project. And the bullet train authority’s own peer review panel said in August that it wasn’t convinced the authority “has acquired the staff, process changes, controls and resources to take on such a massive contracting challenge.”

To a degree, the dispute is about what strategy makes long-term completion more likely:

Should we build an electrified high-speed line through the Central Valley and wow riders there to build demand for funding the extensions to more populous regions of the state?

Or should we start with investments in Los Angeles and San Francisco that have to be made to upgrade existing infrastructure for a future bullet train, and that would in the meantime create better service, lure more riders, and generate demand to complete the entire north-south project?

Martin Wachs, who serves on that peer review panel, said he advocated for the latter when discussions began many years ago. He’s still a believer in the entire project, which could spawn development and jobs at station stops up and down the state, but he also thinks shifting some of the money to metropolitan areas makes sense.

An infusion of several billion dollars into both the Bay Area and Southern California rail systems would pay for a number of upgrades, Wachs said. Trains could run more frequently and safely, the number of road crossings could be reduced, double-tracking would eliminate delays where north- and southbound trains use the same tracks.

Wachs noted a report by Metrolink that estimated ridership between Burbank and Anaheim could double with such improvements, relieving congestion and reducing auto emissions.

I asked Friedman about recent reports of declining ridership on some transit lines, partly because of the rise of car-hailing services, and she said that may be all the more reason to invest more.

“I think people use transit when it’s more convenient,” she said, telling me she often travels by train from the Glendale station to the Irvine station to visit her mother, gladly avoiding the misery of sitting in traffic on Interstate 5. Investing in that line could mean longer trains or more frequent trains.

Friedman said she’s not advocating for curtailing construction in the San Joaquin Valley, but for proceeding without electrifying the tracks for high-speed travel. Trains would still travel 135 miles an hour or so, she said.

Among legislators lining up with Friedman are Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) and Assemblyman Tom Daly (D-Anaheim). Rendon called the plan not a way to end the high-speed rail dream in California, but to save it. In July, Daly told The Times:

“I can’t stand by and watch billions of dollars being spend in the hopes of future ridership in the Central Valley, while there is a thirst for faster and better train service in Orange and Los Angeles counties.”

Unsurprisingly, people in the San Joaquin Valley see this a little differently, preferring to stay the course rather than let San Francisco and Los Angeles raid the kitty for their own benefit.

“Keep high-speed rail money in the Valley, where it can link jobs to housing,” said a headline on a Fresno Bee op-ed by State Sen. Cathleen Galgiani (D-Stockton). She noted that Gov. Gavin Newsom is still on board to stick with the plan.

But is he? A lot of people, including those who closely follow the bullet train’s starts and stops, aren’t entirely sure where the governor stands, especially given that his first comment on the topic made it sound as if he was ready to abandon the whole project. If he’s all in, it’d be nice to hear him explain how he expects to finance a project that is years from completion and underfunded by billions.

When Friedman called the current situation “a bit of a mess,” she was being kind.

The bullet train has traveled with all the speed of a desert tortoise.

It’s been a debacle, but with a plan to switch tracks and benefit the most possible people, I’m on board.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.