A push to keep death records from the public gains support in Ventura County

- Share via

In a move that 1st Amendment advocates say could be a step back for California’s open records law, Ventura County leaders agreed this week to sponsor state legislation that would bar the disclosure of death records to the public.

The Ventura County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously Tuesday to find legislators willing to introduce a bill that would keep autopsy reports and death investigations private. The legislation has not been drafted, and the specifics of the proposed change have not been made clear.

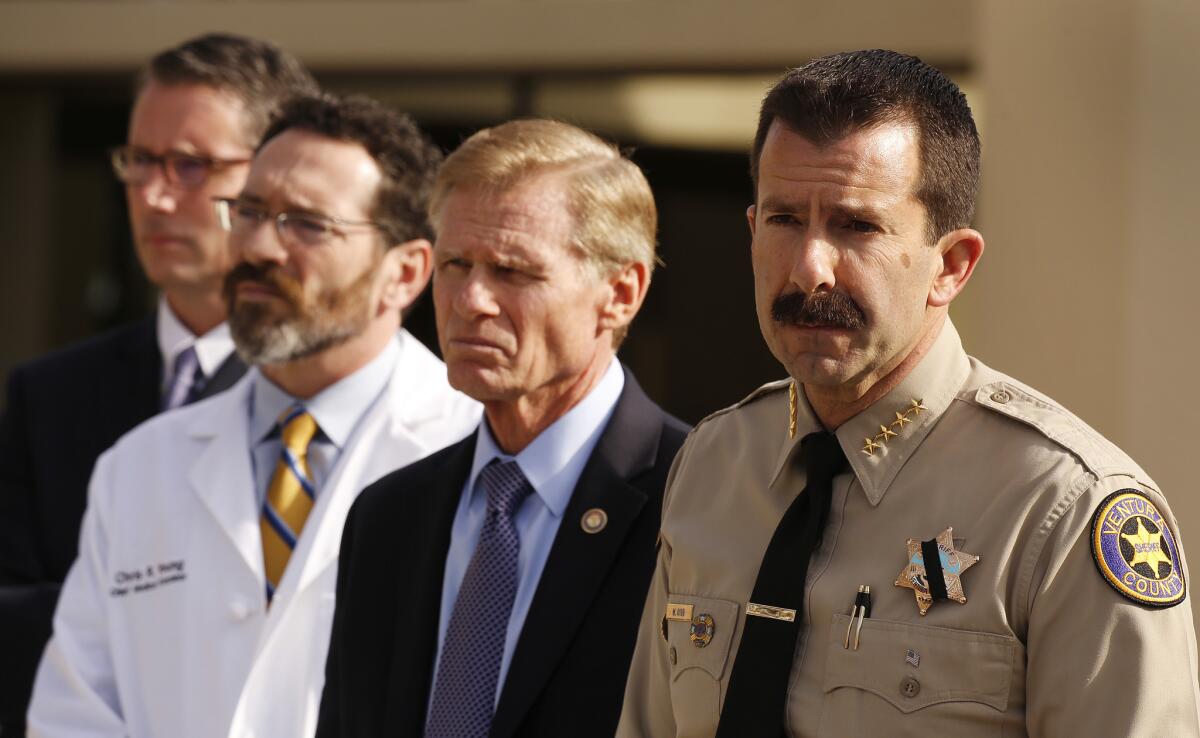

Dr. Christopher Young, the county’s chief medical examiner, indicated that he is in favor of a law that would not allow for the release of death records to the public, which would include journalists. Young said the state’s law governing the release of death records — the California Public Records Act — is murky and “does not clearly protect the privacy of families.”

Privacy rights awarded to individuals under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, which shields a person’s medical records from public review, should extend after death, Young said. He added that death records often contain personal information about a person’s health, medical history, detailed descriptions of their anatomy, their living situation and exactly how they died.

“The reports document a person’s worst day and a family’s worst nightmare. If you’ve never had a member of your family or friend die under these circumstances requiring a medical examiner’s investigation, it’s hard to fully appreciate the sadness and loss. ... It’s an extremely personal and private time,” he said.

Ron Thomas, whose son Kelly Thomas died days after he was beaten by Fullerton police in 2011, said the details contained in his son’s autopsy report came to light in court and were widely report by the media.

Still, he firmly believes families should be the ones to decide whether documents are released to the public. Even years after his son’s death, Thomas has opposed any release of those records.

“The family should have the final say, not the Freedom of Information Act, not a district attorney, not a judge. What’s contained in there is so personal,” he said. “The actual report, the whole thing, I don’t think anyone should have a right to that except the family.”

The medical examiner’s office in Ventura County receives about 1,000 requests for records each year. However, in the aftermath of the Thousand Oaks Borderline Bar and Grill shooting, which killed 12 people in November 2018, requests for records soared, county officials wrote in a memo to the board.

Supervisor Kelly Long said she supports the law change to protect the privacy of the families whose loved ones were killed at Borderline.

“It’s remiss that it’s not in our legislative platform right now,” she said.

The Ventura County Star, which first reported on the vote, wrote that the criminal investigation into the mass shooting is reportedly coming to a close and officials have said they would release autopsy records once the investigation is concluded.

“Some families have requested reports and will likely share that information freely,” Young said. “Other families have contacted me directly and pled with me not to release these reports. They are horrified at the thought of these graphic descriptions of their relatives being released to the public.”

Glen Smith, the litigation director for the First Amendment Coalition, said while the disclosure of death records is a sensitive area, there are larger issues of public interest that necessitate the release of those documents. The information in such reports are frequently used in accountability reporting done by newspapers on a variety of issues. Some have prompted investigations that have changed policies on issues such as foster care conditions for children, job site safety, consumer product safety and police accountability, Smith said.

“These records are essential from a public health and safety standpoint for the public to really understand what happened to that individual, and if someone is responsible, ensure that they are being held responsible, or if changes need to be made, that they are in fact being made,” he said. “Just throwing a blanket over all of it, when you think it through, would remove from public view some very important records.”

The documents are also critical for government accountability, he said.

Young told supervisors that his office has “nothing to hide” and agrees that their work should be transparent. He suggested the medical examiner’s office could be held accountable in the form of annual reports that document types and numbers of deaths and how they were handled by coroner‘s officials.

But Smith contends that an annual report doesn’t go far enough.

“The public records act does not operate at the pleasure of the government,” he said. “The whole reason it’s there is for public accountability and transparency and not for any government official to create summaries and say, ‘Yes, we can let the public know about this, and this other stuff we’re not going to give out.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.