Judge recommends revoking license of UCLA doctor accused of sexually assaulting colleagues

- Share via

A UCLA cardiologist should have his medical license revoked for sexually assaulting a fellow doctor while he was working at L.A. County-USC Medical Center, according to an administrative law judge.

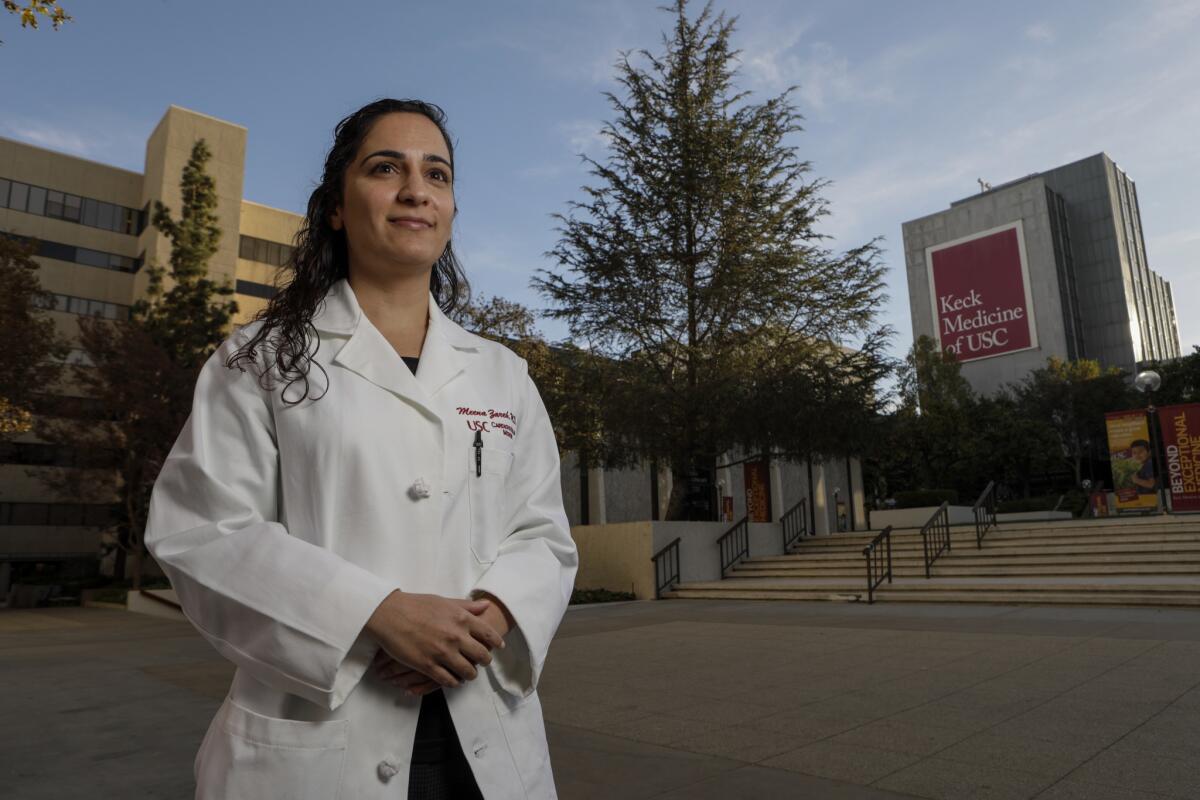

Dr. Meena Zareh said Dr. Guillermo Andres Cortes forcibly kissed her, stuck his tongue in her mouth and penetrated her vagina with his finger in a call room at the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services’ flagship hospital in November 2015.

Zareh “proved by clear and convincing evidence” that Cortes assaulted her, according to a decision by Administrative Law Judge Thomas Heller last month. Cortes’ medical license should be stripped for “unprofessional conduct” as a result, Heller wrote.

An administrative law judge’s decision about sex assault claims against Dr. Guillermo Andres Cortes

Two other women, both of whom were County-USC physicians under Cortes’ supervision, also accused him of sexual assault, according to Heller’s report. One said Cortes had sex with her when she was drunk, unconscious and unable to give consent. The other, who had consensual sex with Cortes, said he also raped her repeatedly.

In testimony before Heller late last year, Cortes claimed the incident with Zareh never happened and his sexual relationships with the other two women were consensual.

In his decision, Heller wrote that the evidence was convincing in Zareh’s case but not in the other two. It’s now up to the state medical board to accept or reject Heller’s proposed decision to revoke Cortes’ license. The board could also reduce the punishment, reject it entirely or ask Heller to take more evidence in the case.

“Revocation is a very harsh penalty for what was found,” said Peter Osinoff, Cortes’ attorney. “Obviously we disagree with the findings.”

Zareh said officials at both USC’s medical school and the county hospital retaliated against her after she spoke up.

First, she said, they suggested she delay her own medical education to avoid working in proximity to Cortes. Then she said they suggested she leave and continue her education somewhere else. Then they scheduled her to work the same shift as Cortes on more than one occasion.

“Instead of encountering a supportive environment, I was retaliated against by very top leadership in an attempt to silence me,” Zareh said in an interview. “I had two major institutions punishing me for reporting a [predator] ... and those people are still in power.”

Zareh filed a civil suit, which is ongoing, against the county health department and USC’s medical school.

Rochessa Washington, spokeswoman for the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, said the county took “immediate and appropriate actions” in response to Zareh’s accusation. But she declined to offer more details because “the matter is in active litigation.”

A spokesperson for USC ‘s medical school said once made aware of Zareh’s allegations, “we took appropriate actions in response.” .

“I think this is a classic example of women not being believed,” said Leslie Levy, Zareh’s lawyer. “She had no motive to make this up. This put her career at risk.”

In her testimony before Heller, Zareh acknowledged she found Cortes physically attractive. From her text messages, it appears the two had flirted before the alleged assault. But they had never dated and there was nothing that led her to expect what she claimed he did in the small, windowless room at County-USC hospital, Zareh said.

After she asked for his advice about a critically ill patient, Zareh said Cortes gestured for her to follow him into the locked room. Once inside, she said, he positioned his cellphone on a desk so he could watch a soccer game, they discussed the patient briefly and then he attacked her.

She said she told him “no” and “stop” but he didn’t. When he shoved his right hand down the front of her scrub pants and penetrated her with his finger, she said she told him to “get your hand out of there.” He eventually did, but not before scratching her vagina with his fingernail, Zareh said.

In his testimony, Cortes said he never touched Zareh in the call room and had been more interested in the soccer game. He said she asked him about an application she had filed to USC’s prestigious cardiology fellowship program, but he told her something like, “USC is not for you.” Cortes speculated that might be why Zareh accused him of assault.

But, Heller wrote, “it is hard to believe such a statement would motivate [Zareh] to fabricate a sexual assault claim.”

After breaking free from the attack, which Zareh said lasted between three and five minutes, she immediately told a close friend and colleague at the hospital. But she did not report it to administrators for months, until she was accepted to the cardiology program and realized she would have to work closely with Cortes.

The county placed Cortes on paid leave while it investigated, but eventually found the evidence of the assault in the call room inconclusive and allowed him to return to work.

The case was referred to authorities, but prosecutors declined to file a felony charge of penetration by force. A deputy district attorney said the case lacked enough evidence “at this time,” according to a memo obtained by The Times.

Cortes moved on to a job at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine, but he was suspended with pay in May 2018 after an accusation was filed regarding the sexual assault claims with the state medical board. He remains on paid leave, according to the university. Cortes was fired from a job at Arrowhead Regional Medical Center for the same reason.

Cortes’ state medical license is listed as current and active. His attorney said Cortes is not working as a physician at this time.

Last year, a national oversight panel revoked accreditation for the USC medical school’s fellowship in cardiovascular disease. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education did not publicly state the reasons for the action, but it came a year after Zareh’s accusation was filed with the state medical board.

In a memo at the time, Dr. Laura Mosqueda, dean of USC’s medical school, said the move was based on concerns about “resident safety and wellness processes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.