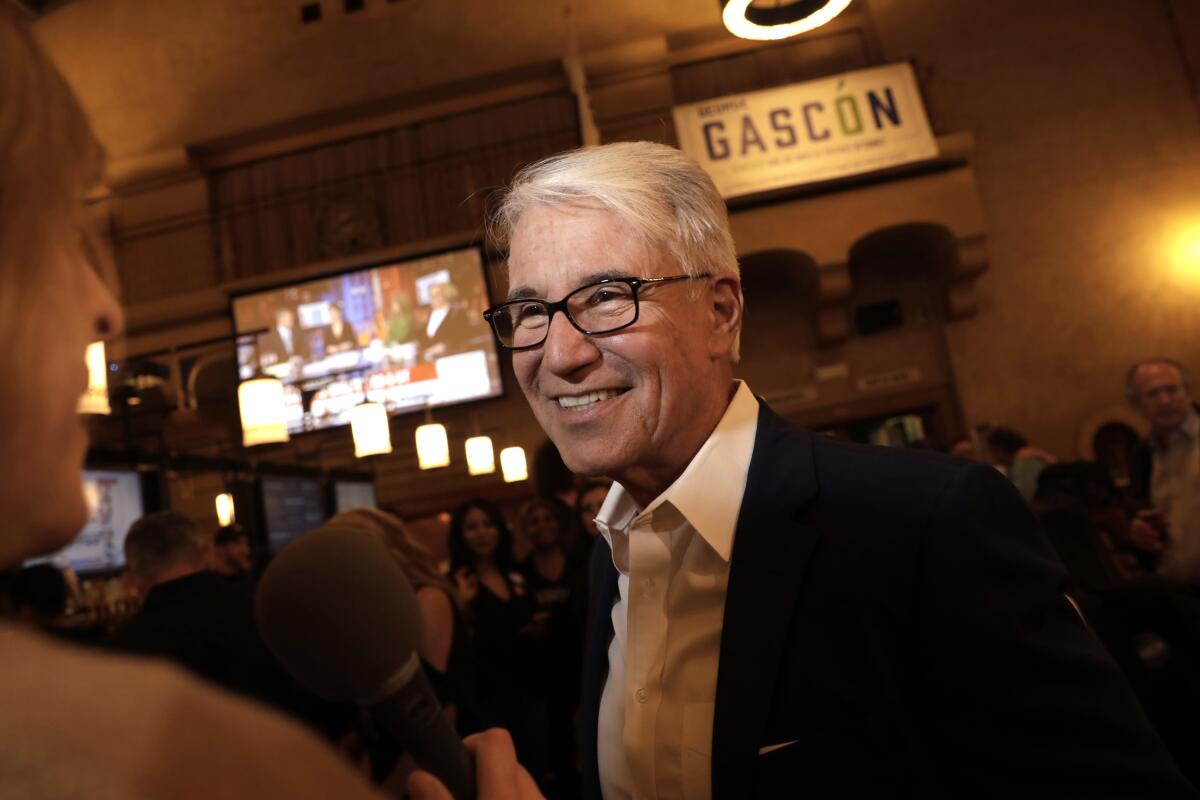

As George Gascón takes office, campaign promises will be put to the test

- Share via

Changes are coming to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office. And if recent weeks are any indication, they will not come gradually.

Since he defeated incumbent Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey in November, George Gascón has left little doubt that when he is sworn in Monday he will set to work fulfilling campaign promises to overhaul an office he has criticized as being part of an unfair criminal justice system.

When it was time for his first major meeting after being elected, he did away with expectations that he would turn first to the office’s 1,200 prosecutors and met instead with Black Lives Matter organizers, who were some of Lacey’s harshest critics.

And when Gascón announced his transition team days later, the list featured civil rights lawyers, bail reform activists and a man who was once wrongfully convicted by L.A. County prosecutors. The only law enforcement official on the roster is a young deputy district attorney who announced a run against Lacey last year before dropping out to become part of Gascón’s campaign team.

The moves by the former San Francisco district attorney were in line with the promises he made on the campaign trail but nonetheless made for a jarring departure from the traditional, tough-on-crime approach Lacey and her predecessor Steve Cooley brought to the job for the last two decades.

In recent weeks, Gascón has also doubled down on promises to enact sweeping policy changes when he takes office. Prosecutors will be barred from seeking the death penalty, trying juveniles as adults or pursuing sentencing enhancements for gang-related crimes. At least four shootings by police that Lacey declined to file charges on will be reexamined for potential prosecution, and more could come up for consideration.

As Gascón ascends to one of the most powerful law enforcement posts in California, his early policy initiatives have drawn a range of reactions: praise from criminal justice reformers as well as concern that has sometimes bordered on panic from some of the prosecutors in the office he is about to inherit, wary of the changes he’s pursuing.

“What you’re going to see, and I’m sure you’ve seen before, is that when progressive prosecutors do stuff, it’s an outrage and it’s a scandal. Because their opposition wants something to scream about,” said Philadelphia Dist. Atty. Larry Krasner, who ran on ideas similar to Gascón’s. “George will get that. He will also smile, because he’s been here before.”

In a recent interview, Gascón downplayed the idea that he would face tense opposition from prosecutors, noting that many who were critical of Lacey had reached out to him during the campaign. Instead, he said, he’s choosing to focus on long-term cultural shifts he plans to bring to the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office.

An early signal of Gascón’s plans to prioritize rehabilitation of defendants over punishment was the team he assembled to carry out his transition into the office. The roster includes a former federal public defender, one of the architects of a major bail reform effort, and a number of civil rights attorneys and lawyers who specialize in reviewing the integrity of convictions.

“I was elected by the people and this community will have a seat at the table as we work to modernize our criminal justice system,” he said when announcing his team. “Those that have been directly impacted by the work of this office have unique insights that are integral to an effective administration.”

The combination of Gascón breaking bread with Black Lives Matter and building a transition team that includes just one prosecutor unnerved several deputy district attorneys, who spoke to The Times on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. Some said they worried his plans to seek life in prison instead of the death penalty in capital murder cases will seriously upset victims’ families. Others fear his broader policy initiatives will warp the mission of the office.

“I think a lot of people are worried about becoming social workers when they’ve spent their lives being lawyers,” one deputy district attorney said. “A lot us are in the position that we’re not just seeing a change in the administration, but we’re seeing a change in the core function of what we’ve chosen as our career.”

Another veteran prosecutor said that though they weren’t overly concerned about Gascón’s promised shake-ups, they would urge the new district attorney to slow the implementation of some of his broader policy changes, such as those involving juvenile defendants and sentencing enhancements.

“Everyone is kind of taking a wait-and-see approach because there’s going to be a lot of ramifications for unilaterally doing any big policy changes without doing a full review of all of those cases,” the prosecutor said. “Some are easier to do than others.”

After an election cycle that saw law enforcement unions spend millions to try and defeat him, Gascón’s relationship with rank-and-file officers also is likely to be strained by his pledge to reexamine a number of fatal shootings by police that Lacey found to be within the law.

Ruben Hernandez was stunned to hear that Gascón would take a second look at the shooting death of his 19-year-old brother, Hector Morejon, who was unarmed when he was gunned down in April 2015. Although Lacey didn’t file charges in the case, her prosecutors excoriated Long Beach Police Officer Jeffrey Meyer in a 17-page memo for poor tactics that led to the shooting.

“Everything was presented and the evidence was there,” Hernandez said. “If that was any other civilian, he would have been charged and found guilty.”

After winning an election largely framed around questions of how police use force against people of color, Gascón’s decision to meet with Black Lives Matter organizers and family members of people killed by police shortly after he won served as a potent signal of his plans as district attorney. Although some prosecutors have privately complained about the meeting with Black Lives Matter demonstrators, Gascón said he felt it was important to acknowledge the group after Lacey refused to speak with them for years.

“Frankly, for me, it was very symbolic that that was my first public meeting…. These are groups that have endured a great deal of personal pain and suffering,” he said.

The meeting proved tense and emotional at times, with some people referencing Gascón’s record of not prosecuting police in fatal shootings in San Francisco and promising to protest him if he did the same in L.A.

But Gascón said he was pleased with the overall tenor of the discussion. He hoped his relationship with activists could remain cordial, but he said that if he is to truly function as an independent prosecutor, he would probably clash with groups on all sides of the political spectrum.

“Are we going to sometimes disagree? Of course. Just like I’m going to disagree with the police sometimes too,” he said. “The job is calling balls, balls, and strikes, strikes.”

Gascón is also planning to significantly alter the way the office reviews questionable convictions. Though Lacey often touted her Conviction Review Unit, the division lagged far behind other large prosecutor’s offices in the U.S., in part because of a policy set by Lacey that limited the types of cases the unit could review.

“I think if we review a case and we come to the conclusion it was either a wrongful conviction, or procedurally we are unlikely to succeed, then dragging the case for years and having somebody in custody … is frankly amoral,” he said.

No matter what criticisms and opposition Gascón has to weather from inside the office or elsewhere, Krasner said the new top prosecutor needs to remember who elected him, and why.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that the people are with him. What he’s up against are the institutions and the old ways of doing things,” he said. “Over time, especially as we are able to change culture within our offices … in the long run we win.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.