San Diego Mayor Faulconer eyes next chapter as term ends

The Republican’s likely run for governor would be a test of state’s political temperature, analysts say

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — When he was younger, Kevin Faulconer had a job cleaning carpets. He walked in after messes happened.

That experience served him well in his political career, winning special elections for San Diego City Council and then San Diego mayor after scandals forced the incumbents out of office.

Now, with his seven-year term as mayor concluded, the 53-year-old Republican is positioning himself to run for California governor as Gov. Gavin Newsom comes under fire for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Newsom is also the subject of a recall effort, the sixth attempt by various conservatives to unseat him since his election in 2018. The first five fizzled.

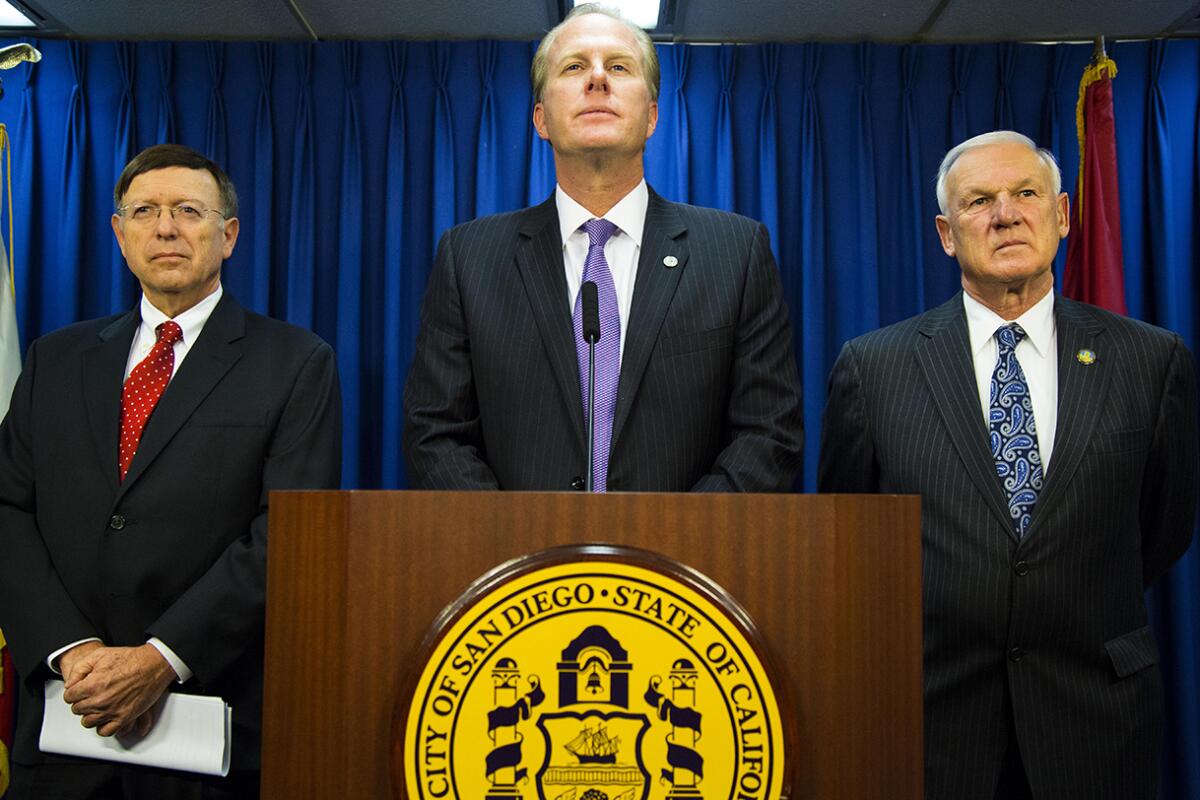

Key events in the seven years Kevin Faulconer was mayor of San Diego

The newest one, which started in June, has collected 800,000 signatures, according to organizers. They would need almost 700,000 more by March 17 to qualify for the ballot, and probably closer to 1 million more to account for disqualified petition-signers.

That’s unlikely, political analysts say, because the pandemic makes it harder to solicit signatures and because the recall backers haven’t raised enough money to fund the effort.

But renewed lockdowns in the state, designed to curb a surge in coronavirus infections that is filling hospital beds, have distressed already-struggling businesses, churches, parents of school-age children and others. Some are openly defying the orders and directing their ire at Newsom.

Others remain critical of his attendance at a fancy-restaurant dinner party while he was urging Californians to avoid large gatherings. And a widening scandal over hundreds of millions of dollars of unemployment benefits fraudulently paid to prison inmates has people questioning the competence of his administration.

All of that has left the 53-year-old Democrat “facing the biggest political troubles so far in his governorship,” according to a recent story by Politico. The article said his team is “increasingly concerned” about the recall effort.

Watching this unfold is Faulconer, who’s been talked about as a possible gubernatorial candidate ever since he became mayor in 2014, riding into office in the wake of the sexual harassment scandal that chased out Bob Filner.

He said he is seriously considering a run, whether it happens as part of a recall next year or in 2022, when Newsom would be up for reelection. Judging from Faulconer’s public comments touting his accomplishments as he leaves office and his social media posts in recent months criticizing the governor, he’s already honing campaign talking points.

“Faulconer has not only put his toes in the water of the governor’s race,” said Dan Schnur, a former consultant who teaches political communications at USC and UC Berkeley, “he’s waded in up to his waist.”

A blue state

Because of how blue California is — almost twice as many registered voters are Democrats as Republicans — the general thinking among political analysts is that the chaos of a recall might be Faulconer’s best chance to become governor.

Two years ago, Newsom was elected with 62% of the vote, the largest share by a Democratic candidate for governor in state history. A recent survey, conducted before the recent shutdowns, showed that while Californians are pessimistic about the state’s financial future, almost 60% still approve of Newsom’s handling of the economy.

And then there’s this: No Republican has been elected to statewide office since 2006, when Arnold Schwarzenegger won a second term as governor.

“The problem for Faulconer is that he’s too moderate for the modern Trump Republican Party, and he’s a Republican in a very blue state,” said Carl Luna, a political science professor at Mesa College. “I don’t see many options for him at the statewide level.”

But Jack Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College, pointed to Republican governors in Democratic-majority states — Massachusetts and Maryland — as proof that it can be done.

“If he was running for U.S. Senate, I’d say no way,” Pitney said. “But governors are different. And Faulconer has positioned himself well, so if Newsom continues to have troubles, he could have a shot.”

Faulconer positioning himself includes walking a line when it comes to President Trump, who figures to remain a force among Republican loyalists even after he leaves the White House in January.

In June 2016, after Faulconer won reelection as mayor, he was asked what he thought about Trump, who was five months away from defeating Hillary Clinton for the presidency.

“I could never vote for Trump,” Faulconer said then. “His divisive rhetoric is unacceptable and I just could never support him.”

Except that he did, last month, when Trump lost to Joe Biden.

“For me, it was a clear choice on what we needed to do to rebound from COVID,” Faulconer said. “I voted for the president because I thought he was the best person to help restore and energize our economy.”

His support for Trump doesn’t surprise political analysts. “He has to say that, to appeal to the Republican base,” Pitney said. “Otherwise he’d be in trouble in the primary” for governor.

Faulconer said there are limits to his embrace of the president, though, and it stops short of supporting Trump’s ongoing efforts to overturn Biden’s victory.

“I’ve said very clearly, and I’ll say it again: The election is over, and it’s time to come together and move forward as a country.”

Leading the way?

In late 2016, as potential candidates jockeyed to replace termed-out Jerry Brown as governor, a Field Poll showed Faulconer in second place, behind Newsom.

He said that he wasn’t interested, that there was unfinished business for him in San Diego. And then the city got rocked by a hepatitis A outbreak among the homeless that killed 20 people, sickened nearly 600 more and muted any speculation about the mayor seeking higher office.

Faulconer, criticized for being slow to react, looks back now on that time as a turning point, “when we decided we had to change, and that what we needed was a bias toward action.”

Backed by funding from San Diego Padres executive Peter Seidler and others, the city put up tent shelters to reduce the number of people sleeping on sidewalks. It also opened lots for people living in cars and expanded facilities where homeless people can store belongings.

The result has been a drop in the number of homeless people, at least as measured by an annual one-night “point-in-time” count. The tally has limitations, and whom to include in it has changed from year to year. But other big counties do a similar survey and their numbers have gone up.

“San Diego is leading the way,” Faulconer said. It’s not hard to imagine homelessness being a centerpiece of any campaign he runs for governor — especially since polls show the public giving Newsom low marks on that front.

But there were also several controversial real estate deals, including the lease-to-purchase agreement for a downtown high-rise that has cost the city more than $23 million in rent for a building it can’t occupy because of asbestos and other issues.

Luna, the Mesa College professor, said Faulconer was a “mainstream, very cautious mayor, a moderate Republican with a no-frills, no-excitement approach.”

Luna also cited street repairs and homelessness issues as Faulconer achievements, but added that “the big swings he took — on a new Chargers stadium and the convention center expansion — never came to fruition. And another big project, the Qualcomm Stadium redevelopment in Mission Valley, went forward without him” — winning at the polls over a competing proposal the mayor endorsed.

Vladimir Kogan, an associate professor of political science at Ohio State University and co-author of the 2011 book “Paradise Plundered: Fiscal Crisis and Governance Failures in San Diego,” said Faulconer’s record is mixed.

He noted that one of the city’s long-running financial problems — a projected deficit in pension payments to retired city workers — remains unsolved, as does a backlog of deferred maintenance in city buildings at Balboa Park and elsewhere.

On the plus side, he pointed to changes in community plans, rental-unit preservation policies, and construction regulations aimed at boosting affordable housing, an ever-pressing concern in a county where the median resale price for a single-family home hit $715,000 in September.

“Those actions could make a difference in the city for a long time to come,” Kogan said.

Two political questions

Faulconer said there’s no timetable for a decision on whether to run for governor.

“I’m going to take some time off and enjoy the holidays with my family,” he said. He joked about a long list of “to do” items at their Point Loma home.

He’s been appointed a visiting professor at Pepperdine University, in the School of Public Policy, where he will teach a graduate course called “Innovative Local Leadership.” His appointment begins in January.

One likely topic: Working across party lines.

He sees that as one of his strengths, getting things done as the rare Republican mayor of a major city whose voters are predominantly Democrats. And with a Democratic-majority City Council. He used his ability to speak Spanish to make inroads with Latino voters who have traditionally favored Democrats.

“If you treat people with dignity and respect, even if you have differences, you can find common ground on a way forward,” he said.

A Faulconer run for governor would be a test of that proposition, said Schnur, the college lecturer who served as communications director for Pete Wilson, another former San Diego mayor who went on to the top job in Sacramento.

“Faulconer would actually be testing two political questions,” Schnur said. “One is how far right have California Republicans moved, and the second is, how far left has California as a state moved? It’s entirely possible that in the Trump era, California Republicans have moved further right than he can go. It’s also possible that the state has moved so far left over the past decade that he would have a difficult time competing against a Democratic incumbent.

“But if both questions break for him? He has the potential to be a very formidable candidate.”

Wilkens writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.