How long will hate have to go unanswered after explosion at rabidly antigay church?

- Share via

Three years ago, Delfin Bruce Mejia arrived in El Monte to open First Works Baptist Church and ostensibly proclaim the word of God.

Instead, the formerly registered security guard has stuck to spewing dunderheaded damnations.

Women who wear tights? “Hoochie mamas.” The city where he preaches? “Ghetto.” Vaccines? “Unclean.” He’s even hated on Día de los Muertos.

But Mejia eventually made a name for himself among hate-watch groups for antigay rhetoric of the vilest kind imaginable.

At national conferences, Mejia has ripped apart LGBTQ pride flags and openly wished for the American government to execute “fags.” He has proudly described himself from the pulpit as “homo-hatin’” and called one critic a “stinking, filthy sodomite” and another a “wicked dyke.”

On social media, the father of three tells critics to “hang yourself.” He not only shared on Twitter last year a picture captioned “West Hollywood 2022” with his face superimposed on an Islamic State fighter who was about to throw someone off a roof, but also wrote “I love it.”

Mejia somehow kept a quiet presence locally until the beginning of 2021, when activists launched an offensive against the reprobate. They submitted a petition with more than 15,000 signatures to El Monte Mayor Jessica Ancona asking her to help shut down First Works. Next came a raucous protest on Jan. 17 outside the storefront ministry during morning and evening services that featured a car caravan, dancing, bullhorns and the chant “We’re here, we’re queer, we don’t want Bruce Mejia here.”

This past Sunday was supposed to be the biggest action yet: a rally outside City Hall with a drag show, a march to Mejia’s church and prizes for the best-dressed. Instead, First Works sat empty.

Its squat building was red-tagged. The day before, someone set off a bomb that shattered its windows and damaged its frame.

The FBI, which is investigating the crime, says there are no suspects right now; El Monte Police Chief David Reynoso stressed to my colleague Alex Wigglesworth on Saturday that “it wouldn’t be fair in any way, shape or form to link” the explosion and demonstrators.

But that hasn’t stopped First Works supporters from around the world from condemning Keep El Monte Friendly, the main group behind the anti-Mejia movement.

Three members — 22-year-old Abigail Capiendo, her 29-year-old cousin Hans Hernandez and 21-year-old Ayble Juarez — met me in a park Sunday morning while First Works held its services from an undisclosed location. The trio’s nerves were frayed from the hundreds of threats sent to them and other members.

And they were upset on multiple levels.

Upset that anyone might think their group is responsible for the bombing.

“Hate versus hate never wins,” said Capiendo, a Pasadena City College student. “We’d never give them a reason to confirm what they think of us.”

Upset at the attack itself.

“What if it went off during their service when we’d be outside?” Hernandez asked. “Imagine all the people inside, and all of us outside. So many injuries and maybe even deaths — it makes me sick.”

And upset that Mejia is now playing the martyr, and that their activism against a proud hatemonger needs to lay low for a while.

“It hinders us,” said Juarez, a San Francisco State undergrad. “We had momentum.”

Mejia didn’t return multiple requests for comment. But First Works livestreamed his Sunday sermon on YouTube. After denouncing the “terrorists” and “sodomites” whom he claimed blasted his church, Mejia giddily cited multiple biblical verses about the glories of persecution. Congregants laughed and proclaimed “Amen!” when he described as “exciting” the events of the previous 36 hours.

“Everyone thinks we’re like —,” Mejia said as he cut himself off and pretended to cower. He then straightened up and snickered. “We’re just going like, ‘This is kind of cool!’ We don’t want a boring life. … We want buildings to blow up. Because there’s only one life to live.

“There’s only one life to live, folks,” he repeated. “Might as well go out in a blaze of glory.”

Capiendo, Hernandez and Juarez never imagined that someone like Mejia might bring such open anti-LGBTQ hostility to their hometown.

“I’ve led a good life as an openly gay man,” said Hernandez, while Juarez — who identifies as a trans male — said “there was never a direct attack on me” when he attended Arroyo High School.

At the same time, however, both felt “there was an underbelly of hate” that they could never quite put a finger on.

Call it the El Monte way.

The San Gabriel Valley city has a surprisingly long history of outsiders moving in to set up their bigotry business.

This is a city where civic leaders long celebrated the exploits of the so-called Monte Boys, a 19th century posse that went around Southern California to lend their lynching services. Southern-born evangelists were El Monte’s most prominent Klansmen during the 1920s; in the 1960s, the American Nazi Party relocated its West Coast office from Glendale to a house off of Peck Road.

“Hate groups see El Monte as a strategic center to spread their movement, a gateway to other communities,” says Romeo Guzman, co-director of the South El Monte Arts Posse, a collective dedicated to unearthing the hidden histories of the area. “So Mejia is not new except this dude’s brown. He could be a kid you grew up with.”

But Guzman also points out that the youngsters behind Keep El Monte Friendly — a play on the city’s slogan — are tapping into a long history of locals telling troublesome carpetbaggers to get out.

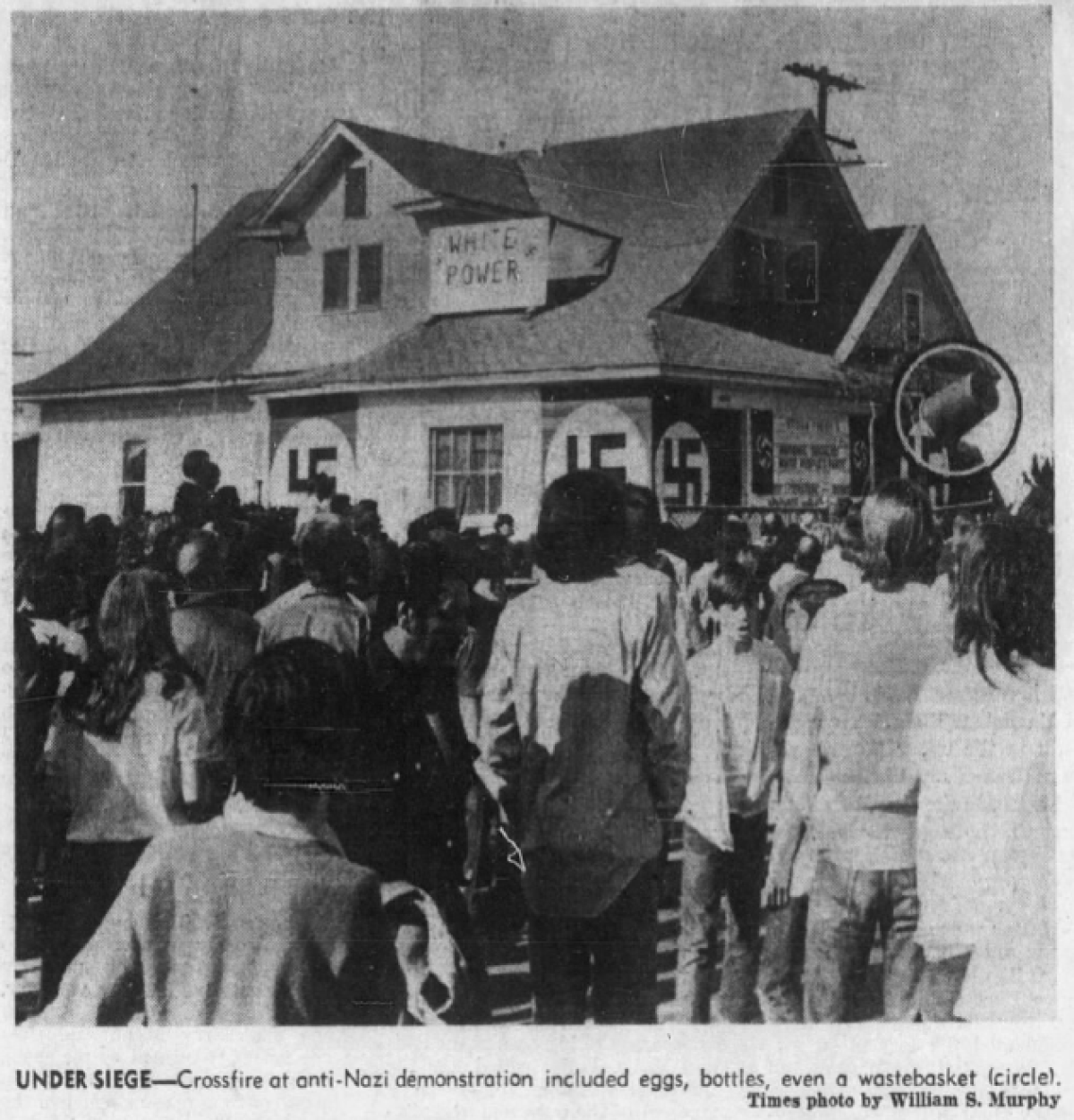

Mexican Americans successfully fought against school and housing segregation after World War II. In 1972, more than 1,000 protesters faced off with rocks and bottles against Nazis at their headquarters, resulting in 40 arrests.

“What they see is what their neighborhood shouldn’t be like,” Guzman said of Keep El Monte Friendly and their predecessors. “So of course they’ll organize.”

That’s what crossed Juarez’s mind when he found out about First Works just three weeks ago.

While they plan no further actions against Mejia until “we know who did it,” Hernandez said of the explosion, he and others are already looking to the day First Works leaves. They’re looking at other pressing issues in El Monte such as gentrification, hunger and the lack of an LGBTQ youth center.

Keep El Monte Friendly has also received requests for help from people in cities that host pastors associated with Mejia and see the First Works bombing as the first skirmish in a long war. Like Mejia’s violently twisted misreading of the teachings of Christ, that too is a shame.

“It puts us in a bad position,” said Hernandez, “but we’ve never encouraged violence. We’re on the right side of this.”

“Winning against hate here has been done before,” Juarez said. “We can do it again.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.