Vaccinated people can get ‘breakthrough’ infections: How worried should we be?

- Share via

With coronavirus cases spreading rapidly throughout California and the nation, reports of infections among those who are fully vaccinated for COVID-19 are increasingly drawing attention.

But while these “breakthrough” cases are sometimes highlighted as a precautionary tale — a signal of the shots’ shortcomings — the reality is that the vaccinations remain as consistently effective as ever where it counts: protecting people against severe illness.

That remains true, officials say, even as Los Angeles County health officials shared a seemingly ominous data point Thursday: 20% of newly diagnosed coronavirus cases in June occurred among vaccinated people. Less than two weeks ago, they said over 99% of COVID-19 cases were among the unvaccinated.

At first blush, these numbers may seem to disagree with each other. But a closer look at the data underscores some key findings cited by public health experts, epidemiologists and infectious disease experts in California and by federal officials.

There are two things occurring: More than half of Californians are now fully vaccinated, yet coronavirus transmission has gone up. And while coronavirus case rates are rising in both vaccinated and unvaccinated people, the rates continue to be much worse in unvaccinated people — a trend that’s expected when viral transmission rises.

Indeed, on Friday, L.A. County reported 3,058 new cases. That means the county has confirmed 10,000 cases just in the last four days.

In June, 20% of coronavirus cases in L.A. County were among vaccinated people. Health experts say that’s not surprising and point to the ultimate success of vaccines.

Why are there cases among vaccinated people increasing?

The following two statements can be true at the same time:

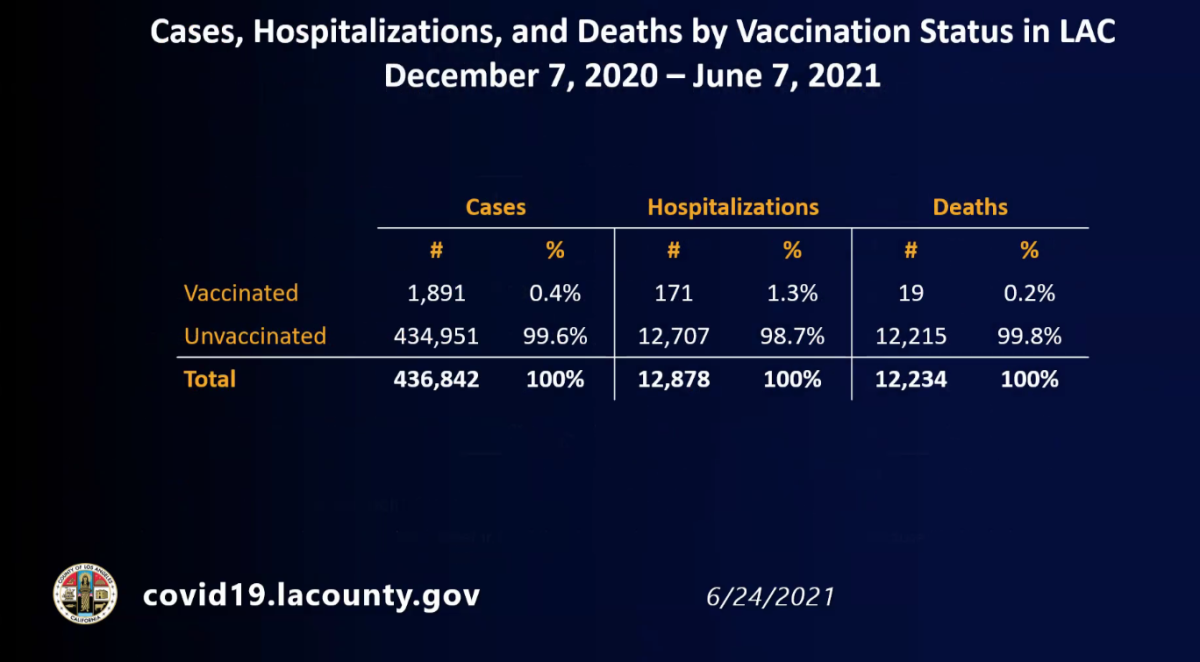

Between Dec. 7 and June 7, the unvaccinated accounted for 99.6% of L.A. County’s coronavirus cases, 98.7% of COVID-19 hospitalizations and 99.8% of deaths.

Out of all coronavirus cases confirmed countywide in June, 20% occurred in residents who were fully vaccinated.

The first sentence speaks to the extraordinary effectiveness of the vaccines. Yes, the period between Dec. 7 and June 7 does cover a time period when vaccine supply was limited. But it also provides a viewpoint into what hospitals are seeing and explains why doctors are so convinced at the effectiveness and importance of the vaccines: Extraordinarily few hospitalizations and deaths have occurred among vaccinated people.

The latter percentage is not so surprising as it might initially seem.

Say, for instance, there were roughly 1,000 coronavirus cases in a month among fully vaccinated people, and there were 4,000 more coronavirus cases among people who were either unvaccinated or partially unvaccinated. In this community, a population of 10 million people was split: Half were vaccinated, and half were not.

One could focus on how 20% of the coronavirus cases occurred among vaccinated people.

But one could also point out that how, for every 100,000 residents, 10 vaccinated people tested positive, and 40 unvaccinated people tested positive. That means unvaccinated people, in this hypothetical example, are four times as likely to test positive for the virus.

Statewide, officials note that while there are instances of vaccinated people becoming infected, the risk remains much more pronounced for the unvaccinated.

From July 7 to 14, the average case rate among unvaccinated Californians was 13 per 100,000, according to the state Department of Public Health. Among those who had been vaccinated, the comparable figure was 2 per 100,000.

A small number of COVID-19 ‘breakthrough’ cases are expected after vaccination, and health officials say they’re not a cause for alarm

Vaccinations provide a high protection but are not 100%

There is overwhelming evidence that the COVID-19 vaccinations in use in the United States continue to provide a high degree of protection — although not 100% — against severe illness, hospitalization and death.

Earlier this week, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the U.S. government’s top infectious-diseases expert, cited data showing the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines were 95% and 94% effective, respectively, versus symptomatic COVID-19. And in the United States, the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been 72% effective against clinically recognizable disease.

“Infections after vaccination are expected. No vaccine is 100% effective,” he said. “However, even if a vaccine does not completely protect against infection, it usually, if it’s successful, protects against serious disease.”

Nationally, more than 97% of people now hospitalized for COVID-19 have not been vaccinated, according to Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“While seat belts don’t prevent every bad thing that can happen during a car accident, they do provide excellent protection — so much so that we all use them routinely,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “It wouldn’t really make sense to not use a seat belt just because it doesn’t prevent all injuries from car accidents.”

Similarly, she continued, “rejecting a COVID vaccine because they don’t offer 100% protection really ignores the powerful benefits.”

People with weak immune systems should still take special care to talk to their doctors about additional protective measures they may want to take.

Coronavirus infections in Los Angeles County are accelerating amid a surge that has cases and hospitalizations reaching levels not seen in months.

California hasn’t achieved ‘herd immunity’

For all the progress California has made in terms of vaccinations, it’s now clear that the state is still short of achieving “herd immunity” — the level at which enough people have been inoculated or have obtained natural immunity to protect the larger population against the virus.

Even the Bay Area‘s highest-in-the-state vaccination rates aren’t high enough to insulate the region from increasing case counts.

Most Bay Area health officers have urged everyone to wear masks in indoor public spaces regardless of vaccination status. And health officials in Contra Costa, Santa Clara and San Francisco counties are strongly urging employers to consider requiring their workers to get vaccinated.

Increasing community transmission will mean more positive tests — even among the vaccinated

When coronavirus transmission rises, the immune systems of fully vaccinated people may come under increased pressure. And officials say it’s to be expected that more fully vaccinated people, if they are tested, will be positive for the coronavirus.

Consider a fully vaccinated person who enters a crowded room with many unvaccinated people, but there are only two infected, contagious people there.

“My chances [as a vaccinated person] of getting infected were really, really small,” relatively speaking, Ferrer said.

But say the room is filled with 30 unvaccinated, infected people. In that case, “my chances — even as a fully vaccinated person — have just gone up” of acquiring a coronavirus infection, she continued.

However, officials note unvaccinated people are still far more likely to test positive for the virus than those who have rolled up their sleeves.

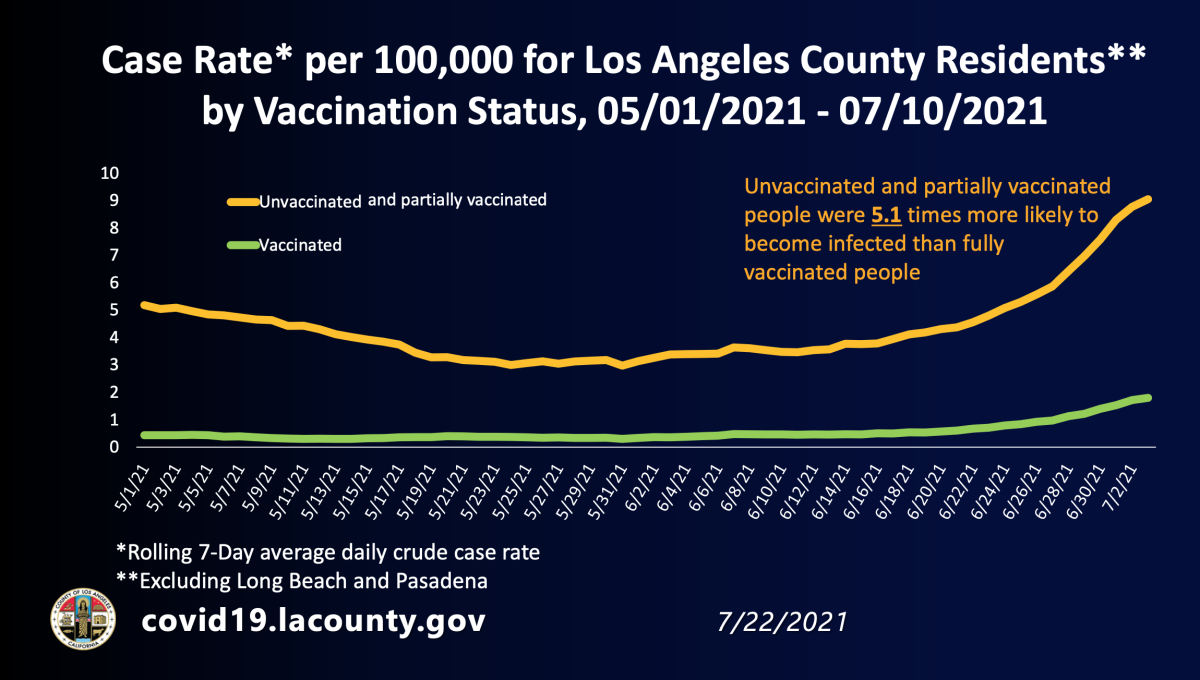

In early July, for every 100,000 L.A. County residents, approximately nine who were either unvaccinated or only partly vaccinated tested positive daily for the coronavirus, according to a chart released by the Department of Public Health. That’s far higher than the daily case rate for fully vaccinated people, for which fewer than two of every 100,000 residents tested positive.

Earlier this year, there were some initial reports out of India suggesting that the coronavirus strain that later became known as the Delta variant was especially worrisome because so many healthcare workers who had been fully vaccinated were nonetheless being infected.

But subsequent analysis later suggested that the vaccines continue to be effective.

It’s not that the Delta variant was more likely to break through the immunity offered by the vaccines compared with previous strains of the coronavirus. It’s that rising circulation of the virus will predictably cause more vaccinated people to eventually test positive.

When health officials say a vaccine is 90% effective, that means that 10% of the time it’s not effective, Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at UC San Francisco, said earlier this year. The more people who are exposed to the coronavirus, the higher the number of so-called breakthrough infections.

“It may not have to do with variants as much as it just has to do with the intensity of the exposure,” Rutherford said.

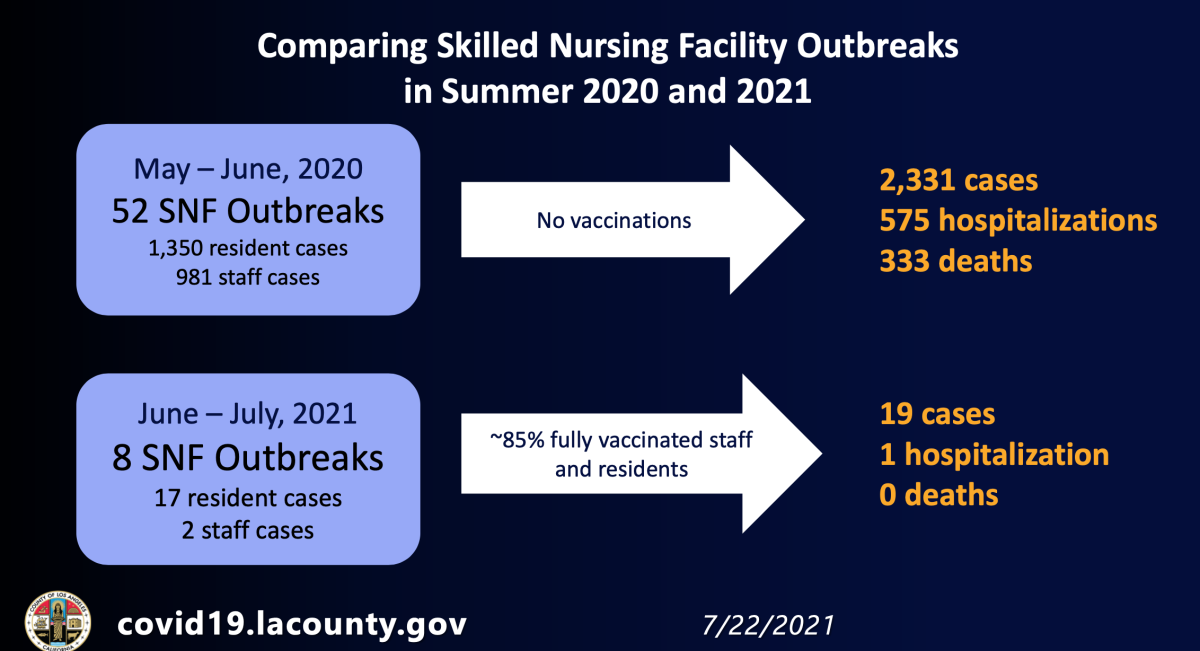

It’s also important to note that in environments where a high percentage of people are vaccinated, cases stay low, as do hospitalizations and deaths.

In May and June of 2020, when the shots were still half a year from public distribution, there were at least 52 outbreaks of the coronavirus at nursing homes in L.A. County, resulting in more than 2,300 cases, 575 hospitalizations and 333 deaths.

But this June and July, with about 85% of nursing home staff and residents now fully vaccinated, there have been only eight outbreaks, resulting in just 19 cases, one hospitalization and no deaths.

A vaccinated person who is infected generally has less to worry about

Not all positive cases of coronavirus necessarily warrant the same degree of concern.

Some vaccinated people who get infected might still feel lousy and experience uncomfortable symptoms. But data consistently show those individuals have a much better chance of not needing to be hospitalized than an unvaccinated person.

“Even for those fully vaccinated people that get infected, they are much less likely to get as ill as unvaccinated people, to require hospitalization and to pass away,” Ferrer said.

Fauci has said that the level of coronavirus in the upper throat of an infected and vaccinated person is “considerably less” than in an unvaccinated person.

Less virus means less severity of disease.

“That’s exactly what your vaccine is supposed to do: It’s fighting the infection in your nose and bringing down the viral load, and you don’t get symptoms,” Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at UC San Francisco, said earlier this month. “I don’t call that a vaccine failure. I call that a success because that’s exactly what your vaccine is supposed to do.”

One-third of California counties are now urging even fully vaccinated people to wear masks indoors as coronavirus cases continue to rise.

Increasingly high transmission rates and the return of masks

One reason L.A. County is now requiring everyone to wear masks in indoor public settings, regardless of vaccination status, is to get more unvaccinated people back in the habit of using face coverings in hopes of cutting down transmission of the disease.

Another reason is the concern that vaccinated people might — in a very small number of situations, according to Ferrer — become carriers of the virus with either no or very mild symptoms and be able to unknowingly infect other people.

It’s a reasonable assumption to make that an infected vaccinated person will be less likely than an unvaccinated person to pass the virus on to someone else, Fauci said. That’s because vaccinated people who are infected have considerably lower levels of virus in their throat compared with unvaccinated people.

“So even though we are seeing infections after vaccination ... the effectiveness against severe disease is still substantial,” he said.

Times staff writer Andrew J. Campa contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.