Would you quit your job for $110,000? This California swordfish catcher said no

- Share via

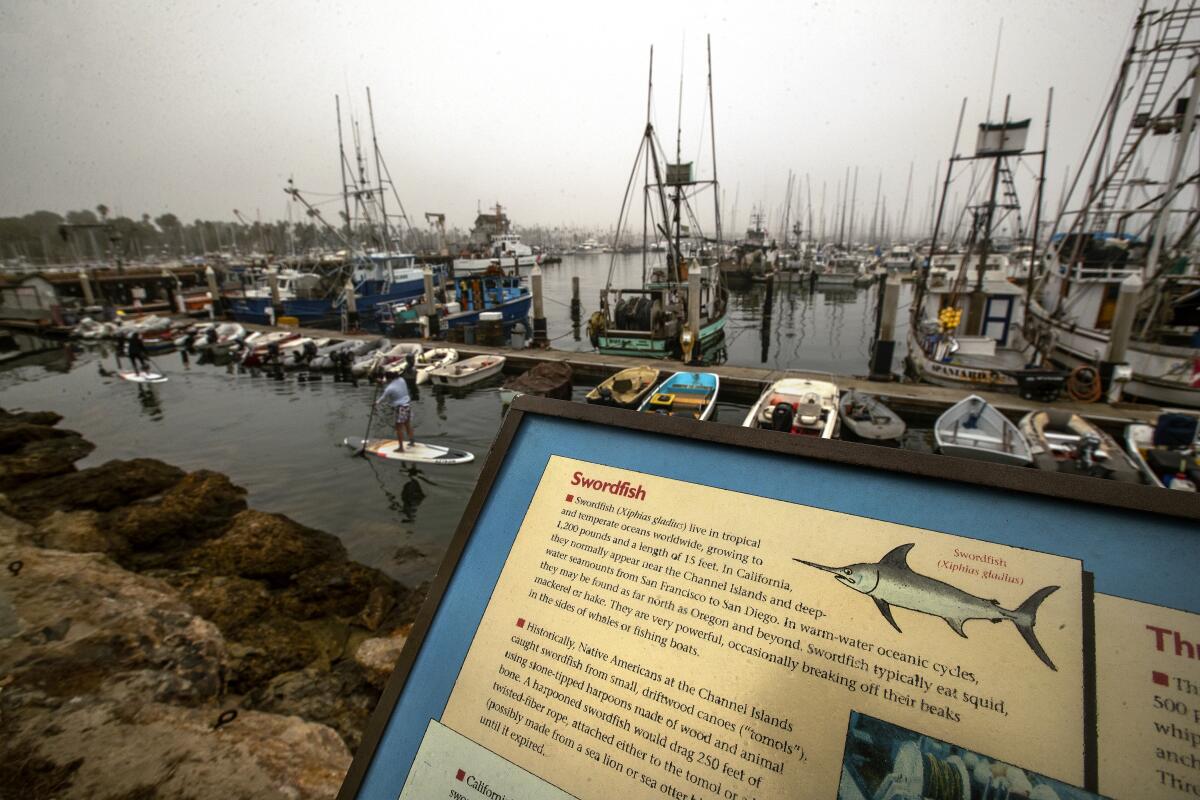

SANTA BARBARA — As the morning fog peeled off the docks of Santa Barbara Harbor recently, fisherman Gary Burke eyed all that’s left of a fleet that once helped satisfy America’s insatiable appetite for swordfish: four old vessels with splotches of rust showing through peeling paint.

Decades ago, there were more than 100 such ships in Santa Barbara alone, towing mile-long drift gill nets in choppy seas far beyond the breakwater. Today, there are perhaps a dozen in the entire United States, and they will probably soon be removed from service.

Hammered by government regulations, foreign competition, soaring fuel and labor costs, fluctuating market prices, a state buy-back program to take nets out of the water, and conflicts with preservationists over incidental entanglements of whales, porpoises, seals, turtles and birds, Burke’s livelihood has gone the way of Southern California fur trappers and dairy farms.

As if all that weren’t enough, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency have issued an advisory warning that swordfish are not safe to eat because they contain high levels of mercury.

In 2021, the price of fresh swordfish has been as much as $22 per pound.

“We’ve been whittled down by regulations and old age,” Burke grumbled as he climbed aboard the 50-foot vessel Tytan, which has been his private domain for 35 years.

At age 75, the tall, easy-mannered fisherman with a replaced knee and rough, callused hands is not as sure-footed as he once was. “In a couple more years, I won’t have the strength to climb into my own boat,” he said.

Until then, “I’m going to keep doing it,” Burke said, a grin spreading across his face.

“They’re putting a good fishery out of business for no good reason,” he said. “Most of the nation’s swordfish is imported, even though scientists say swordfish stock off California is healthy.

“That doesn’t make sense to me, and it isn’t right,” he said, shaking his head and gazing out at the harbor promenade.

That kind of talk is not the only reason that Burke has become something of a local hero on the waterfront. He is the lead plaintiff in an ongoing lawsuit challenging a California program to phase out swordfish gill netting by 2024.

In a separate case earlier this year, a federal court judge cast his line in favor of three California swordfish netters led by Burke and struck down a new federal rule that will shut down their fishery if it accidentally kills or injures too many marine mammals or turtles. With plenty of protections already on the books, the judge said, the rule would “threaten the economic viability of the drift gill net fishery while providing minor environmental benefits.”

It was a rare win for what was once one of the major commercial fisheries in California. In the 1980s, the fleet landed more than 7 million pounds of swordfish worth close to $13 million annually, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Since then, landings have declined to less than 1 million pounds worth about $2.5 million.

Now, a state buy-back program is offering $110,000 to each swordfish netter who quits the business. Burke said he turned down the offer.

“I’m glad that Gary and a handful of other guys are fighting back,” said Kim Selkoe, executive director of the nonprofit Commercial Fishermen of Santa Barbara. “They are courageous representatives of a fishery that still has great value.”

Mark Helvey, a former National Marine Fisheries Service administrator, agrees. “By putting our swordfish netters out of business, we’re just moving the industry to less regulated fisheries elsewhere,” he said.

The drift gill net fishery for swordfish began off the coast of Southern California in the late 1970s and quickly grew into one of the major commercial fleets in the state. By the mid-1980s, the arrival of swordfish riding warm currents up from Mexico in autumn and winter to feast on squid and mackerel was drawing an estimated 300 fishermen who unfurled spidery nets to snare them.

The only other commercial fleet targeting swordfish off the West Coast catches fish with harpoons but contributes a fraction of the landings produced by gill netting. The essentials of the gill net fishery haven’t changed all that much over the decades. Gill net gear consists of a panel of netting suspended vertically in the water by floats with weights at the bottom. One end of the net is fastened to the vessel and the other end of the net is left free to drift along the current.

The nets are typically unfurled at sunset and allowed to drift during the night in areas where swordfish might be feeding, for example, where warm water meets a cold-water current and scanners have located sardines, anchovies and squid.

The commitment of early gill netters like Burke was huge — in time, financial investment and drive. They stayed out for weeks traveling hundreds of miles out of sight of land, with the sway of the ocean underfoot.

With their own lives and the fate of their cargoes at stake, mechanical problems or dark sky at the horizon were constant concerns.

Back in the day, it was the Wild West on the high seas, Burke recalled. “Most folks have no idea what commercial fishermen went through to put swordfish steaks on their plates.

“Competition was so intense,” he said, “that everybody had secret voice scramblers attached to their on-board radios so that others who might be listening in wouldn’t know where they were or where they were headed.

“If your net got caught in the boat propeller,” he said, “you stripped down, slapped on a snorkel mask, grabbed a knife and dove overboard. Then you tried to hold your breath long enough to cut it off.

“It could be a little dangerous out there,” he added, “but a guy could make more than $100,000 a year.”

But unfettered by quotas or regulations, their bycatch was appallingly large. Marine conservation and sportfishing groups called their nets “curtains of death” and pressed for elimination of the gear. Their demands led to the enactment of a series of time and area closures and gear requirements over the last 25 years to reduce the bycatch of marine mammals and turtles.

For example, before the 2001 establishment of the Leatherback Conservation Area closure, which eliminated most swordfish netting north of Point Conception, the fishery operated from the Mexican territorial water border northward to Oregon.

A minimum mesh size of 14 inches across is now required to reduce bycatch of smaller, unwanted species and to optimize the take of larger, more desirable species such as swordfish and bluefin tuna. The use of acoustic warning devices, or pingers, became a requirement in 1997 and significantly reduced entanglements with marine mammals and turtles.

The modifications reduced the rate of endangered sea turtle entanglements by 90% from pre-2001 rates, according to a study co-authored by Stephen Stohs, a NOAA economist.

Despite these improvements, the tide of public opinion was not running their way.

Earlier this year, Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.) submitted a bill that would ban swordfish netting on a federal level and direct regulatory agencies to assist commercial fishermen in converting to potentially new means of catching swordfish with almost no risk of bycatch.

One of them is called “deep-set buoy gear,” and the technology behind it takes advantage of the unique characteristics of swordfish, which spend most daytime hours at depths of 700 to 1,400 feet, coming only occasionally to the surface.

Voracious predators, swordfish can reach almost 1,200 pounds and grow 14 feet in length. They also have a heat exchange system that allows them to warm their brain and unusually large eyes while searching for prey in deep, cold, murky water that is low in oxygen.

Deep-set buoy gear uses a floatation device from which a single line hangs with no more than three hooks attached to it. An 8-pound weight quickly sinks the baited hooks to 1,200 feet beneath the surface, where swordfish are accompanied by few other species. A detection system attached to the gear alerts fishermen when a fish is on the line, allowing for quick retrieval once hooked.

The method is so selective, that swordfish comprise upward of 95% of the fish caught with the gear, said Chugey Sepulveda, senior scientist at the Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research and head of a team that developed the deep-set buoy gear. Rapid processing and the freshness of the landed local product, he says, would bring premium prices at market.

At the recommendation of the Pacific Fishery Management Council and conservation groups including the nonprofit Oceana, NOAA is weighing a proposal to issue up to 300 deep-set buoy gear permits, phased in over a 12-year period in the Southern California Bight.

Oceana, which a year ago donated $1 million to California’s effort to eliminate drift gill nets, estimates that transitioning the state swordfish fishery to methods such as deep-set buoy gear would save at least 27 whales, 548 dolphins, 333 seals and sea lions, 24 sea turtles, and 70 seabirds over 10 years.

It remains to be seen, however, whether commercial fishermen can catch enough swordfish with the new gear to be economically viable. Beyond that, at least one loggerhead turtle has been observed entangled in deep-set buoy gear, according to an environmental impact review of the method.

“At this point, we don’t know how many commercial fishermen will like deep-set buoy gear — or how much of a dent it would put in import markets of swordfish,” NOAA economist Stohs said. “But no matter how big it grows, it will not surpass the number of swordfish harvested with gill nets or long lines.”

Greg Gorga, executive director of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum, which overlooks the harbor, said swordfish netting is one of many California fisheries founded by people wanting to take their chance at high-seas adventure and quick riches— a drive that has resulted in inefficiencies and conflicts that tested the capacity of industry regulators.

“Look over there,” he said, pointing toward a nest of small boats docked side by side. “They were originally designed to haul up abalone, but they overfished it from San Francisco to San Diego. Now, they’re used to harvest sea urchin.”

Next, Gorga pointed to a boat he said was built for salmon fishing, but salmon rarely run in local waters these days.

“What it all means is this,” he said. “Things change, and when they do, it’s tough to see your livelihood disappearing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.