L.A. residents deeply pessimistic about race relations 30 years after riots, poll finds

- Share via

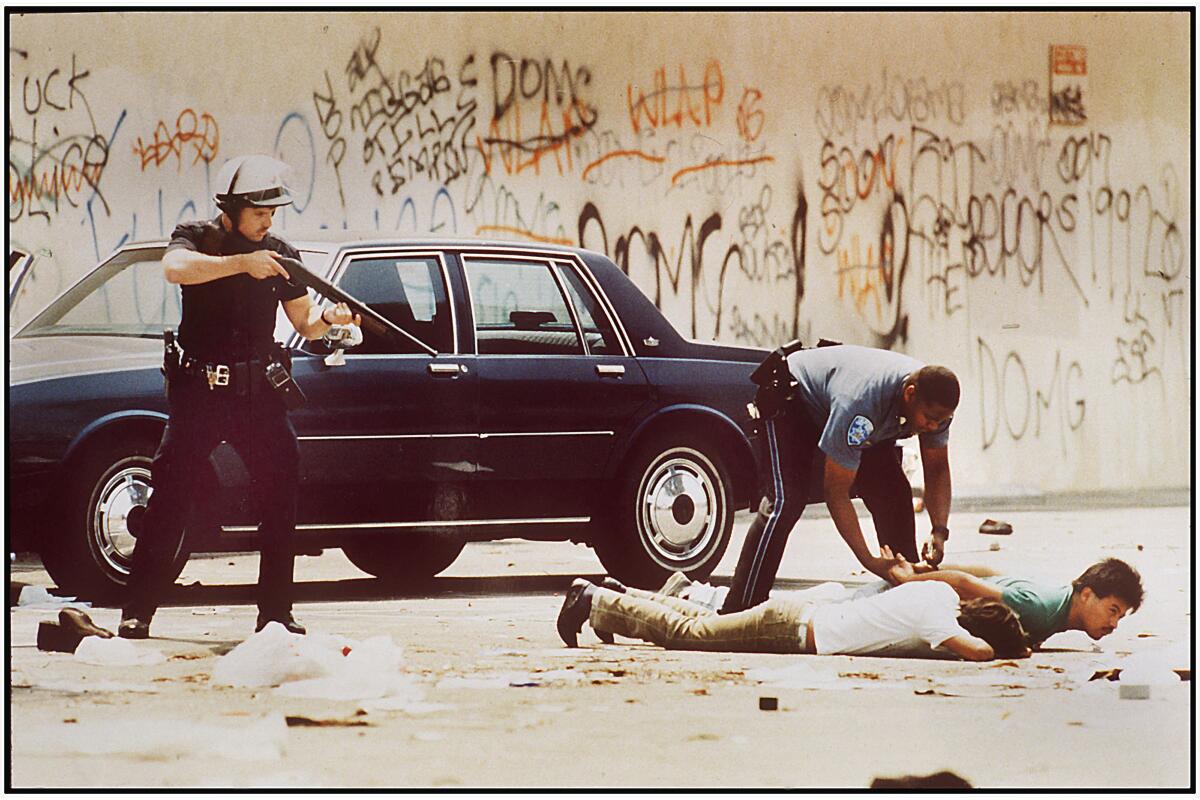

Kenyana Booker was born the year before the 1992 uprising that followed the acquittal of police officers caught on video beating Rodney King.

She grew up in a home where she absorbed the history and the images.

Today, she considers those six riotous days a starting point for Black voices to be heard — though the violence also “put Black people in a bad light,” she said.

After the police killing of George Floyd two years ago, she was encouraged by what she saw as the largely peaceful protests.

But ask her about the prospect of another riot in Los Angeles, and her optimism fades.

“Is it possible? Hell, yeah,” said Booker, 30, a college student and elementary school teacher who lives in South L.A. She noted that too many police interactions turn violent, and too few consequences are enforced.

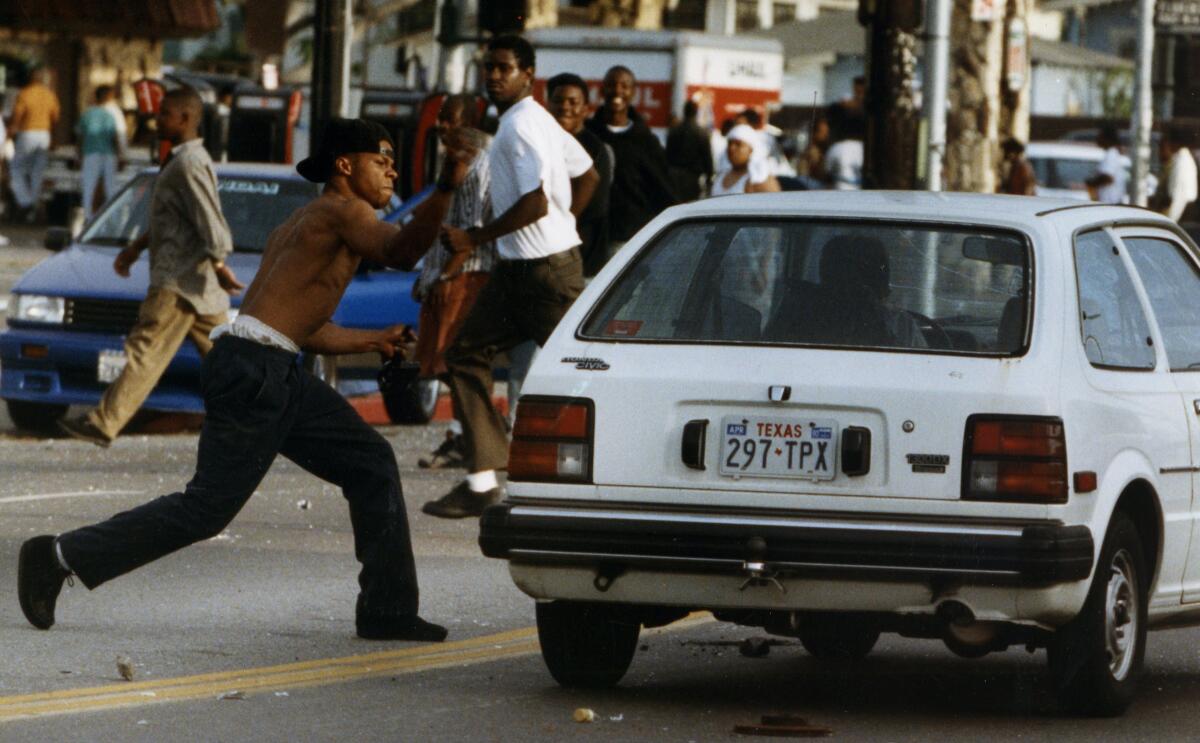

For all the strides that have been made since 1992, many Angelenos believe their city may still be a powder keg, according to a survey by the Thomas and Dorothy Leavey Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University.

The share of Los Angeles residents who expect that another wave of “riots and disturbances” will occur has hit the highest peak since the survey, conducted every five years, launched in 1997.

Five years after the riots, with the city still in recovery mode, 65% of residents thought it was likely that another outbreak would occur before too long.

Over decades, the percentage steadily dropped. But this year, 68% said it was either very or somewhat likely that “other riots and disturbances will occur … in the next five years.”

That finding is not a surprise to UCLA history professor Brenda Stevenson, an expert in African American history. The last several years have been a tumultuous time in Los Angeles and beyond.

“People feel unease about race across the nation,” she said. “They realize that the country is in an awkward situation in regards to race.”

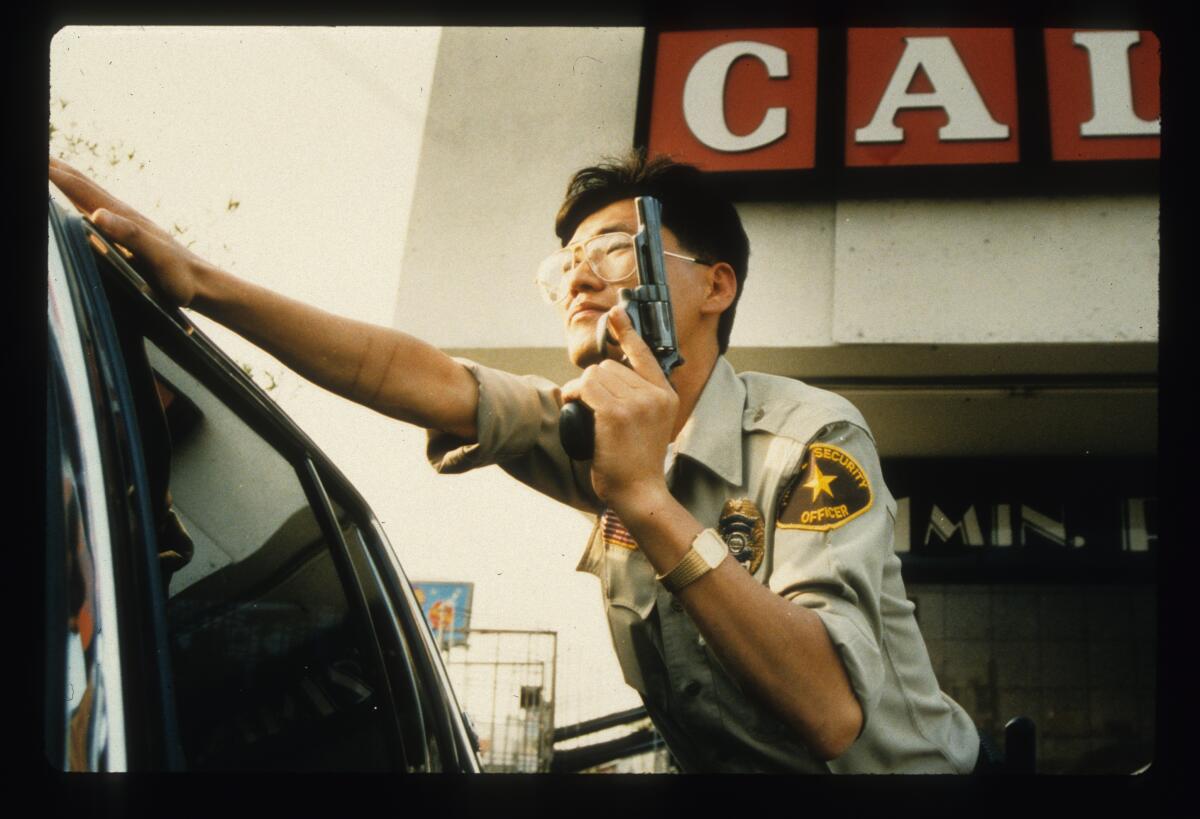

Stevenson ticked off some of the forces that shape perceptions of racial and ethnic enmity: voting rights challenges, biased policing, the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, neighborhood gentrification, the George Floyd protests, the national debate over how race should be taught, and political rhetoric that seems to embrace white supremacist themes.

The survey reflected angst over those forces too. Nearly 40% of residents believe race relations in Los Angeles have worsened over the last four years. The percentage who say that racial and ethnic groups in Los Angeles are getting along badly has increased by 12 points since 2019.

White residents were the most likely to say the city’s ethnic groups get along well. Asian Americans were most likely to say they do not.

People generally had a rosier outlook about race relations in their neighborhoods than in the city as a whole — perhaps a sign that personal relationships matter.

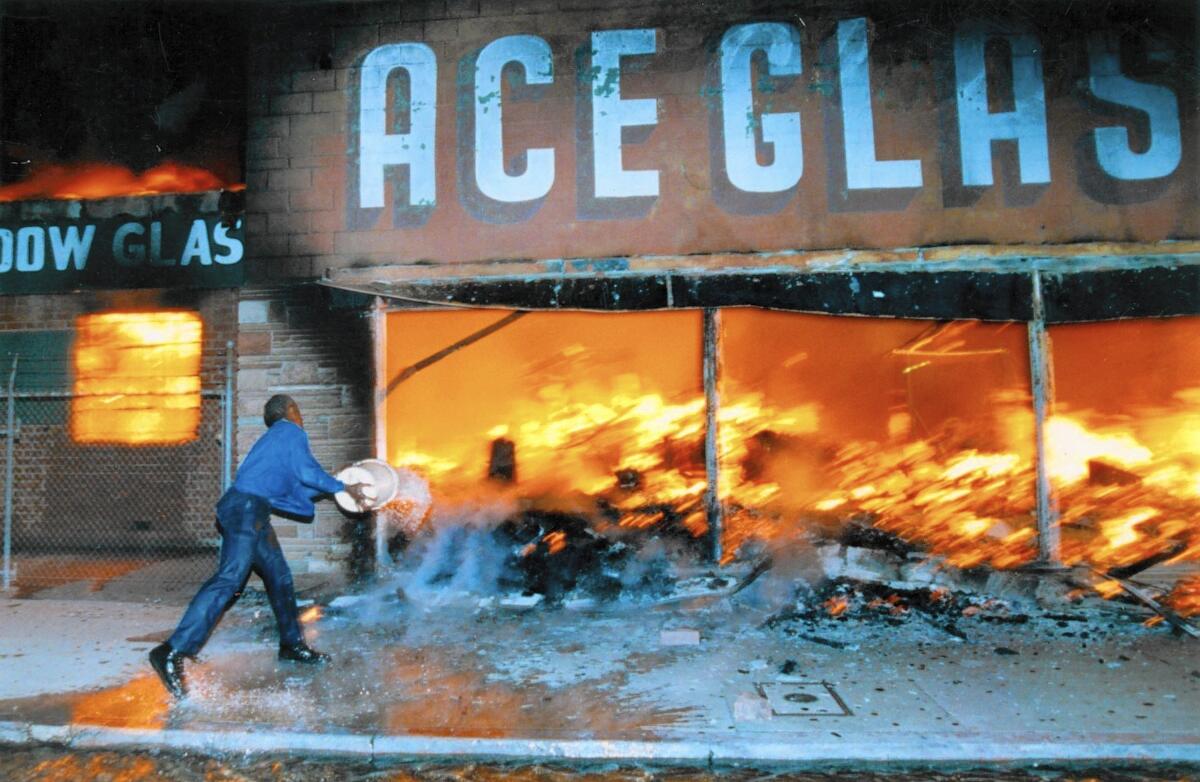

Thirty years ago, Rosie Guzman was working as a seamstress, for a Korean boss, and had to rush home from work when the looting and fires started.

“I remember, we couldn’t leave our homes,” said Guzman, who came to the U.S. from El Salvador in the mid-1980s. “Those were some bad days.”

In hindsight, she understands the riots better now and sympathizes with the hardships and prejudice faced by Black people. She believes those same things could push people to riot again.

“But I still feel things are better, the relationship between the races,” she said.

When she first moved to Koreatown more than 20 years ago, there was a sense of distrust, and Koreans and Latinos kept to themselves, she said.

After the riots, more Latinos moved into the neighborhood and opened businesses. The cultural blending grew to include Blacks and whites who lived in the area.

Guzman now owns a restaurant and three clothing stores in a Koreatown shopping plaza.

“Now, I see Korean and Mexican couples coming into my stores,” she said. “I feel hopeful.”

Read our full coverage of the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots.

After the death of Floyd and the protests that followed, Latia Sneed has felt more supported by her Latino, Asian American and white neighbors and friends. They are now more conscious of the perils faced by Black men, she said.

“People are galvanizing amongst each other,” said Sneed, 36, who is Black and grew up in L.A. “It’s not just about a bunch of Black folks protesting. It’s a bunch of nationalities going against [white supremacist] groups.”

The survey suggests that millennials in Los Angeles may be leading the way.

They polled more optimistic on virtually every question — from how racial and ethnic groups get along to whether their neighborhood and the city are moving in the right direction.

That, said Stevenson, the UCLA professor, is a sign of better times ahead.

When Stevenson moved to Los Angeles 30 years ago, just before the uprising, the city’s ethnic diversity was pioneering, she said.

“It was the new city, the place where we were really going to see where the nation was going,” she said.

She and other residents soon learned a hard lesson, that L.A. “is really not that different from other cities, in the way that race plays out.”

Still, Stevenson doesn’t share the pessimism reflected in the poll findings.

If the riots 30 years ago were a discouraging inflection point, the 2020 protests in the wake of Floyd’s death might be a sign that ethnic divisions are blurring.

“This brought together all kinds of people — young, old, from different classes, races and ethnic groups — who want to move forward, to stand together,” she said. “The whole world is trying to come together, not to lose ground.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.