What about my koi pond? A wealthy L.A. enclave copes with water restrictions

- Share via

The questions came fast and furious for nearly five hours Wednesday night, offering a glimpse into the world of wealth, worry and water.

“We have a few large koi pond [sic] with over 100 fish,” one person said during an angst-filled town hall meeting of the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District. “Is there a special exemption for them?”

“How long can we run water to top off our pools?”

“If we are always under water budget, can we wash our cars once a week?”

Those were among 600 questions posed by some of the more than 1,000 residents who tuned in to the Zoom meeting. Many reside in communities served by Las Virgenes, including Agoura Hills, Hidden Hills, Westlake Village and the celebrity enclave of Calabasas.

Yes, one of the most severe droughts in California history even hits Kardashian country. But in the land of multimillion-dollar homes, the question of water conservation plays out differently than in the neighborhoods where the rest of us live.

Here, a woman bemoans spending $8,000 on drought-tolerant Native Bentgrass that, due to water restrictions, might die “before it can get established.”

Southern California is facing unprecedented water restrictions in the face of the worst drought in 1,200 years. Our Masters of Disasters tell us who to blame.

“I should be able to water it until it gets deep enough roots so it will require very little at that time,” she said.

Here, residents ask the district to provide outreach to their gardeners. Here, the Hidden Hills mayor asks about getting commercial permits for trucks to irrigate large residential properties with recycled water.

It’s a far cry from regions such as the Central Valley, where residential wells fail and poorer residents can go without running water. Where families are forced to buy gallons of precious water from the grocery store to take showers, clean dishes and cook. Where families cut down on showers to save on water bills.

In Las Virgenes, most of the water is used outdoors — 70% of it.

“People here pride themselves on having, in some cases, lush landscaping. There’s places in our district where if you drive around you’ll nod your head and be like, ‘Oh, I see why water usage would be higher here,’ ” said David Pedersen, the water district’s general manager.

“The water usage tends to be higher than average throughout L.A,” he said. “Because of that I feel pressure that we need to really push harder on conservation, because we have more to give, so to speak.”

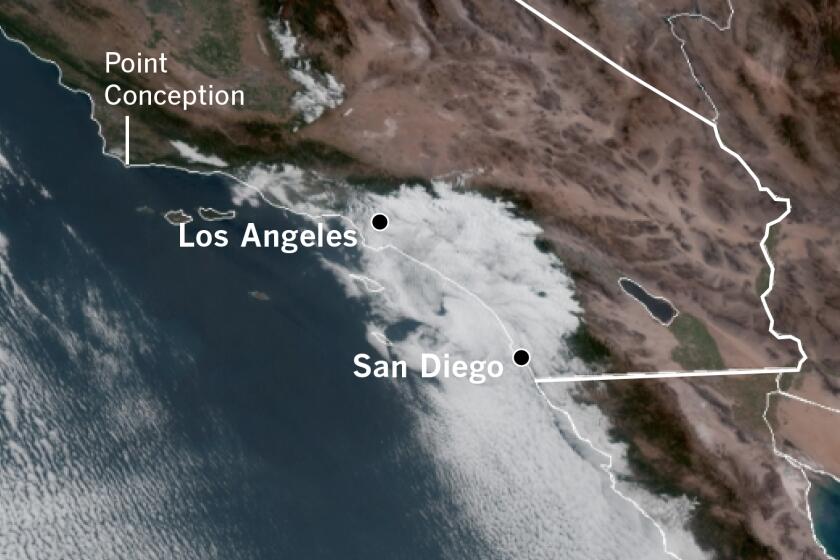

Las Virgenes, which serves about 75,000 residents in western L.A. County, relies on the State Water Project, a Northern California water supply that officials say is dangerously low after the state’s driest-ever start to the year.

Water suppliers in parts of Southern California were ordered to impose severe water restrictions. Details of the new rules are starting to take shape.

Once the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California announced its harshest water restrictions for millions of residents across the region, Las Virgenes staff recommended that residents water their lawns just one day per week.

The MWD’s water restrictions are designed to achieve at least a 35% reduction in water consumption, shrinking usage to about 80 gallons per person per day.

Average residential water use in Las Virgenes Municipal Water District in 2021 was 193 gallons per person per day, according to state data, more than double the statewide average of 91 gallons per person per day.

“We know that this requires a lot of sacrifice, we know that this is not going to be pleasant, we know that lawns will turn brown,” spokesman Mike McNutt told residents during the town hall meeting. “In order for us to be successful, each one of us has the responsibility to reduce water usage.”

A quick Google search of town hall attendees brought up a model, a chief financial officer, a venture capitalist and a mommy blogger.

One man, who questioned why the district was being reactive instead of proactive, said that in his job as a company vice president, “I proactively think of how to save the company, rather than ‘Oh, the company is dying and I need to save it now.’”

It’s not all wealth and Kardashians in the area, though, as evidenced by some of the tensions that flared among community members. One person wrote, “Why does Calabasas look wonderful, while West Lake [sic] Village looks awful?”

“There are many people in Calabasas and Hidden Hills who have all the money in the world and do not care about fines,” another person said. “What will you do?”

In an interview after the town hall, Pedersen acknowledged the tensions among residents in the water district.

Despite official calls for conservation, California cities and towns increased water use by 19% in March.

“There’s kind of this dynamic that’s emerged where there’s big parts of our community … that are willing to make the change and let their lawn die or install drought-tolerant natives,” Pedersen said. “But then what they get really frustrated with is that another part of the community, usually a wealthier part of the community, doesn’t. And then they continue to use a lot of water and then that has an impact on everyone.”

Enforcement, focused on residents who go beyond 150% of their water budget, will involve more than just warnings and fines, Pedersen said.

Before the end of this month, at least 20 to 40 of the most flagrant violators will have flow restrictors installed, Pedersen said. The plate placed on the water meter will limit the amount of water that passes through and make outdoor watering impossible.

“It’s not something we’re excited about, but it is a way we can control water usage for the parts of our community where they may not be sensitive to pricing mechanisms,” Pedersen said. “I’m not fond of heavy-handed enforcement, but we’re in a situation where we just have to do it, because setting rules and policies and restrictions with no enforcement — it doesn’t work.”

During the town hall, as the questions poured in, Las Virgenes employees were ready with answers.

On the koi pond, “fill out a budget request form on our website and we can review your request.” On length of time spent topping off pools: “As long as needed if you stay within your budget.” And, when washing cars, do it at formal carwash facilities where “they recycle 90% of the wash water.”

Residents complained about having to limit watering outdoor landscapes to one day a week, while other districts allowed for two. People asked how they could water perennials, like rose bushes.

“I think it would be helpful for people to understand we live in a Mediterranean ecosystem and water is not a natural, flowing product here,” Mary Sue Maurer, the mayor of Calabasas, said during the meeting. “We need to rethink these lush green lawns and perennials and focus on what the natural environment would be.”

May gray and June gloom are natural heat shields for Southern California. Researchers say their days may be numbered due to climate change.

In response to several questions about pools, district employees urged residents to use pool covers to minimize evaporation. They explained to frustrated customers that golf courses and public parks still look green because they utilize recycled water.

Other questions involved the fire risk in areas where residents would be unable to maintain green space due to water restrictions. One resident said that, if her hill isn’t watered, she wouldn’t be in compliance with her fire insurance.

A few cited the devastating 2018 Woolsey fire, which destroyed more than 1,600 structures and burned nearly 97,000 acres from the Thousand Oaks, Oak Park and Agoura Hills areas north of the 101 Freeway to the beach neighborhoods of Malibu. Three people caught in the flames died.

“I know this is a huge concern, especially watching the fire in Laguna,” said Alicia Weintraub, a Calabasas council member.

District employees said they are meeting with Metropolitan and state officials to try to bring more water to keep the landscape alive through the coming fire season.

The town hall, which Pedersen called the longest public meeting he’s ever done, stretched until the very last question was answered around 10:30 p.m. Beyond just venting frustrations, residents offered ideas on how to save water and improve the supply down the line.

Already, the district is investing in the Pure Water Project Las Virgenes-Triunfo, which takes wastewater, highly purifies it and creates a new source of drinking water. It’s planned to be operational by 2028.

But, for some, the future might not come fast enough.

“Some people want to sell their homes, want to move away,” said Eniko Gold, a Hidden Hills council member. “I share their concern.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.