- Share via

Two years ago, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a big plan for some of California’s littlest children. By 2025, he said, nearly 400,000 4-year-olds would be enrolled in an additional year of public education called transitional kindergarten, or TK, launching what is expected to become the largest universal preschool program in the country.

The $2.7-billion plan, and the legislation that followed, sent school districts scrambling — hiring teachers and aides, building additional classrooms, creating an age-appropriate curriculum — to be ready to welcome the first tranche of newly eligible children in the 2022-23 school year.

But as the first year of this ambitious expansion comes to a close, family interest in the program has been surprisingly lackluster and many school districts are still focused on meeting even the most basic requirements for starting this new grade. Possible funding cuts and ongoing teacher and aide shortages are compounding the pressure — and many educators are uncertain what’s ahead for the 2023-24 school year.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that average daily attendance this year was roughly 91,000 — 28,000 lower than the governor’s estimates. The state is serving 52% of children eligible for TK, much lower than anticipated, according to the LAO.

“The response by local school districts has been quite tepid, and we haven’t seen the surge in family demand that the governor expected,” said Bruce Fuller, a UC Berkeley professor of education and public policy. “After a lot of celebration for getting the legislation passed, we’re making much slower progress than expected. Someone should be worried about that.”

Sarah Neville-Morgan, deputy superintendent at the California Department of Education, however, said she was not surprised by low enrollment numbers as families trickle back into schools after the pandemic.

“It will grow. It’s probably already growing during the school year, and we’ll see more of it next year,” she said. “Something gets passed in a budget and people then expect it to be able to take place the very next day. But it takes time.”

“It’s really a pinch-me moment to be part of history making in California,” added Neville-Morgan, who oversees the state’s early education expansion.

Low enrollment

Interviews with administrators from 18 school districts across the state reveal that low enrollment did have benefits. Most districts were able to shuffle around their existing teachers and use empty classrooms to serve new students this year. Although most school districts already offered limited TK programs, the new state law entitles every 4-year-old a public school seat by the 2025-26 school year, beginning this year with children who turned 5 by Feb. 2, 2023.

But in future years, when more children will qualify and families return from pandemic absences, school officials worry about how they’ll meet demand.

The state added school for 4-year-olds, which benefited enrollment figures but did not offset an overall decline.

Top among concerns are the governor’s 2023-24 budget proposal, which seeks to delay $550 million in funding for early childhood facilities, just when districts say they need the money to build out classroom space. Young children need big spaces for free play. The state requires new TK classrooms to be at least 1,350 square feet and have their own bathroom, equipped with a tiny toilet and extra-low sinks.

The governor’s budget proposal would also require instructional aides to be working toward their teaching credential or childhood development permit. Districts are already struggling to recruit an estimated 16,000 to 19,700 classroom assistants by the 2025-26 school year to meet a new requirement that there be one adult present for every 12 TK students.

A teacher shortage throughout education presents yet another challenge for districts looking to hire an estimated 11,900 to 15,600 new credentialed TK teachers by 2025. By fall 2023, all will be required to have 24 units of early childhood education credits or comparable preschool teaching experience, further narrowing the pool.

“Districts are playing a careful game of ‘Can we get the resources together fast enough and find teachers quickly enough to keep pace with family demand?’ It’s an entitlement, so if too many families show up for not enough teachers, it’s a problem,” Fuller said.

A big year for Long Beach

The Long Beach Unified School District is widely considered a model of a successful TK expansion.

This school year, the district added 15 new TK classes. Nearly 1,200 students showed up, 30% more than last year. They moved from a part day TK to a full day program, nearly doubling instructional time.

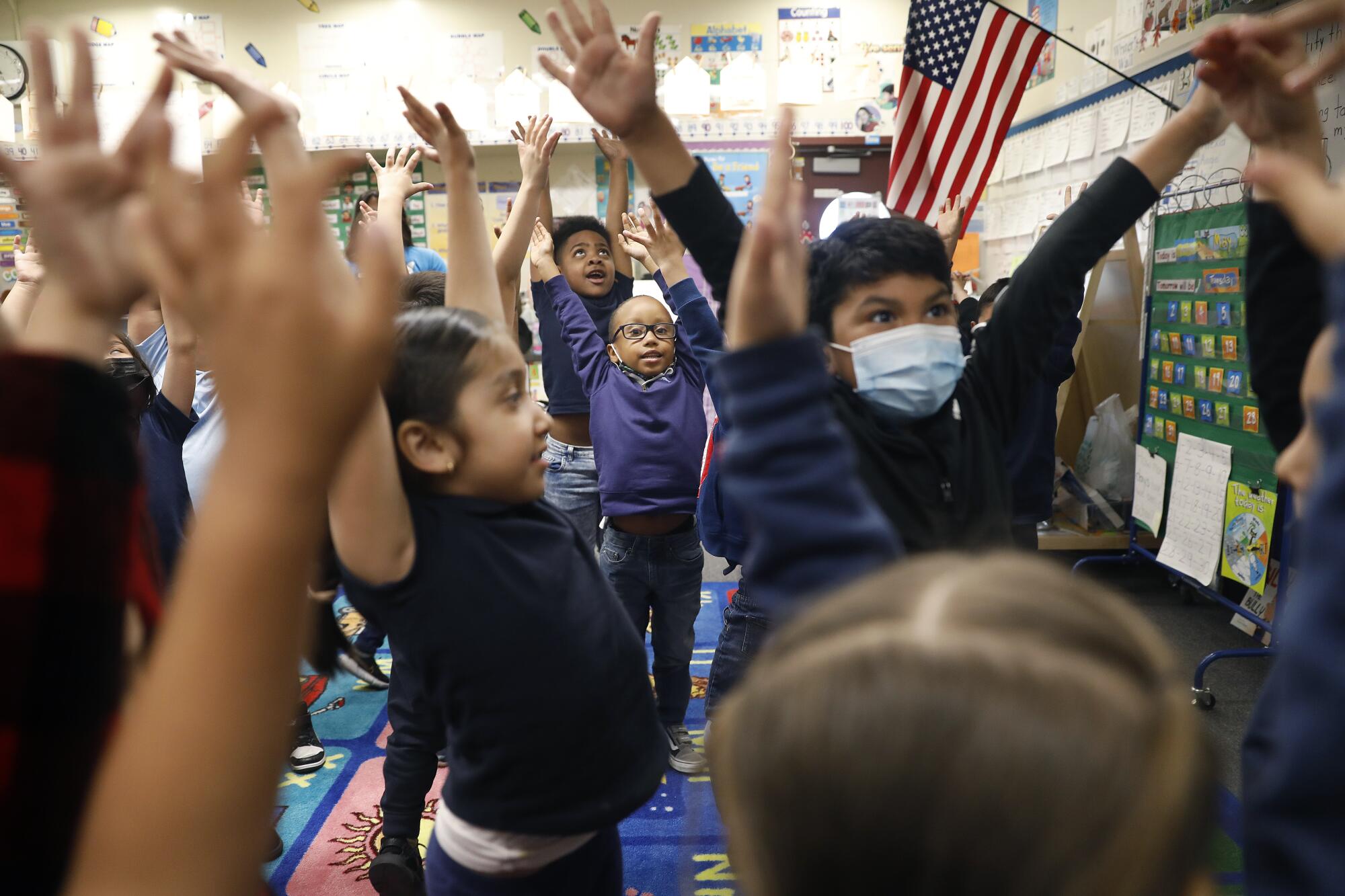

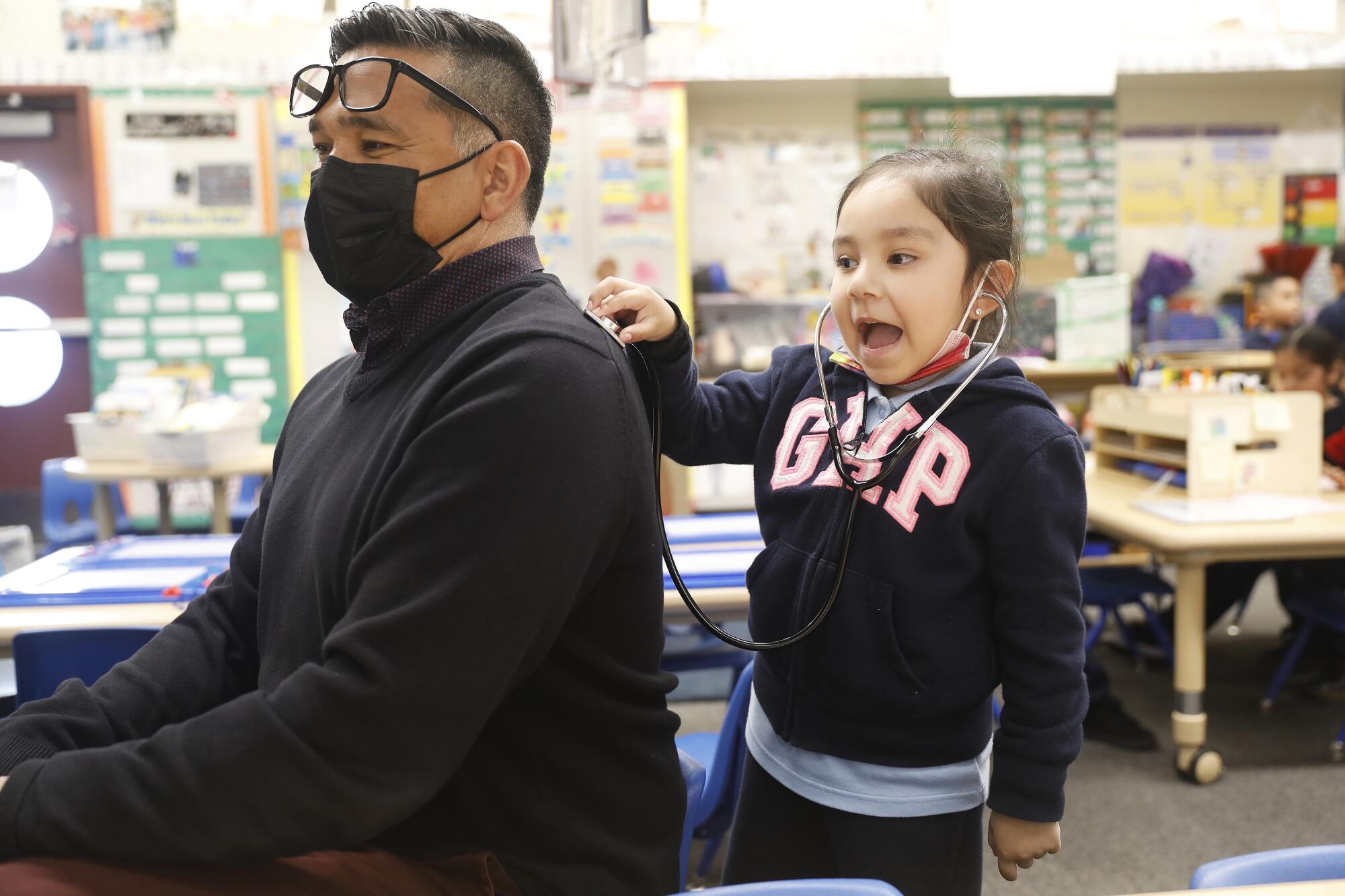

On a recent Monday morning, Micaela Moreno’s TK class at Oropeza Elementary in Long Beach was buzzing.

The walls were covered with children’s drawings, some showing the student’s depictions of why they are “lucky” — family, friends, pets. Homemade phonics posters hung from the ceiling, dangling above a new play kitchen, sand table and bins of colorful blocks and puzzles.

This is Moreno’s 10th year teaching TK, and the changes have been an adjustment. Before the expansion, “we didn’t have this in our class,” she said, pointing to the toy kitchen. “It was like, no time for play. Now we have a lot more educational toys, and we’re expected to use them.”

The children sat in groups of four or five around extra-low tables purchased to accommodate their tiny bodies.

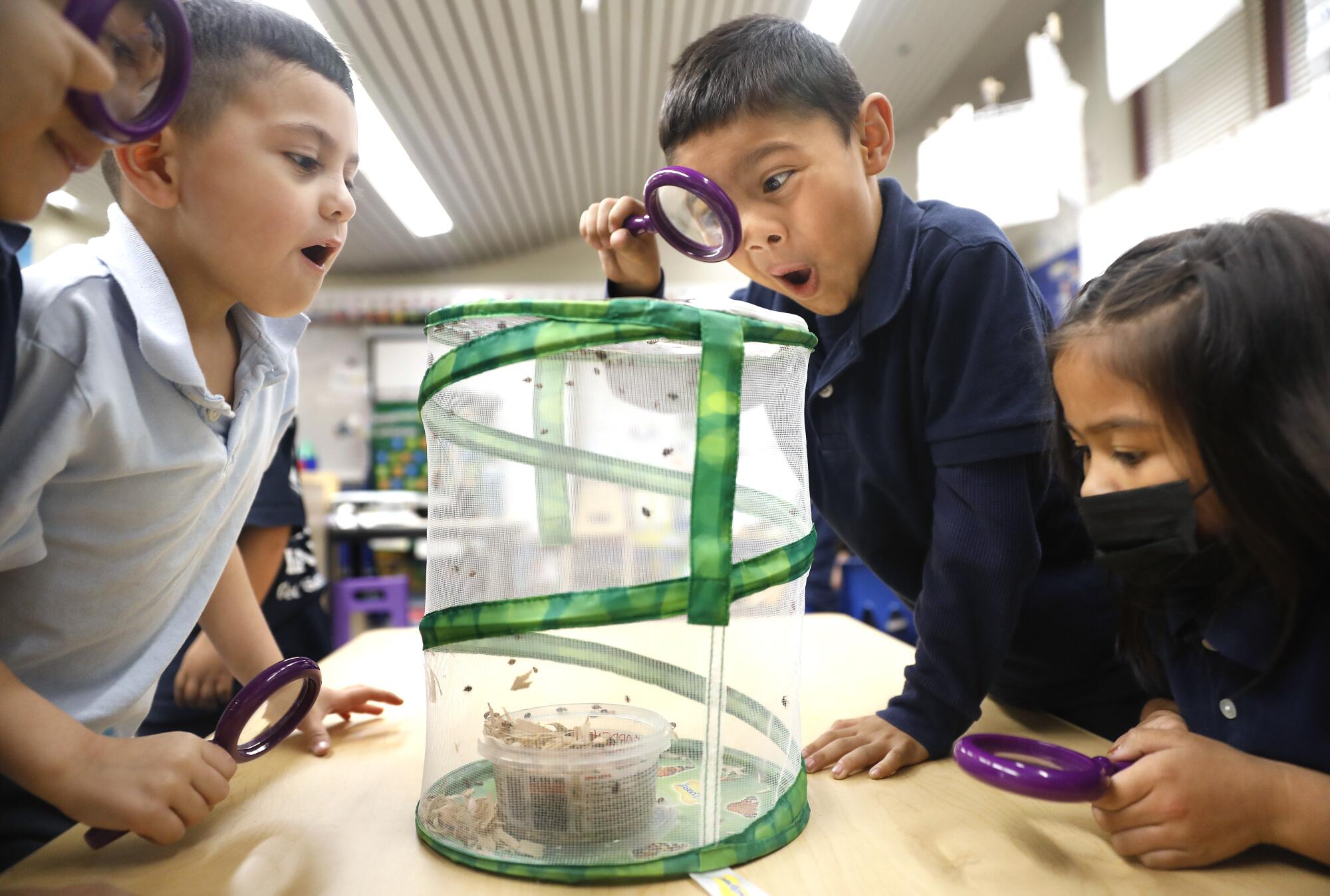

One group huddles around a netted container, peering through magnifying glasses at the ladybugs inside. Though there are five children, Moreno has provided only four magnifying glasses, hoping they will figure out how to share them. But so far, no sharing. She’ll give the children more guidance when they return to the activity tomorrow.

This small experiment is part of a focus this year on social and emotional learning. Learning to work together, take turns and resolve disagreements is particularly important for these children who as toddlers lacked socialization with other children, Moreno said.

“Kids come with a lot of situations where they’re afraid, they’re scared because they’ve been indoors for so long. They’re so young, and their first experiences have been like, ‘Wear your mask, don’t talk to strangers because they could be sick,’ ” she explained. “We have to undo that.”

Aides are hard to hire

Despite the statewide teacher shortage, educators from most of the 18 districts interviewed said finding TK teachers was relatively easy this year — but that’s in large part because of low enrollment.

In Long Beach, hundreds of applicants expressed interest in their 15 new credentialed TK teacher positions. Like most districts interviewed, Long Beach ended up primarily hiring teachers already working in the system who wanted to move to TK, then backfilled.

But districts are likely to have more trouble hiring in future years, said Anna Powell, senior research and policy associate at the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. “That pool is going to reach its limit, and that’s when we’re going to see more TK specific shortages.”

Finding instructional aides is already a bigger challenge — even without the new mandates proposed in the governor’s budget.

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Sunday vetoed Senate Bill 70, saying it had a “laudable” intent but would cost California up to $268 million a year.

“They do make significantly less than TK teachers, so it is a little bit harder, especially in a place like Long Beach where the cost of living is high,” said Brian Moskovitz, assistant superintendent at Long Beach Unified. Although they eventually filled openings, “It’s tenuous. There are times when we have to have subs come in.”

The Pomona Unified School District already has held two job fairs to recruit aides. “There’s a major shortage,” said Deputy Supt. Lilia Fuentes.

Administrators from other districts were not as successful. Milpitas Unified School District in Silicon Valley, for example, still has 32 unfilled openings for instructional aides throughout the district, though not all are in TK.

Assemblymember Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), who was the architect of the TK expansion, said school districts often must compete for low-wage workers with the service industry. In some places, workers can make more money taking orders at Taco Bell.

“It’s Mathematics 101. They can work really hard to craft an amazing 4-year-old in a TK classroom making a little over $15 an hour, or they can help craft the perfect Burrito Supreme in some areas making $30 an hour,” McCarty said.

As districts prepare for future years of the expansion, empty classroom space is also likely to dry up.

In some districts, the impending classroom shortage is already pounding at the door, especially in Central California, where the population is growing fast.

At Clovis Unified School District outside of Fresno, TK enrollment grew by 246 students this year, and the district’s on-staff demographer predicts an additional 1,000 TK students by the 2025-26 school year. That means they need to come up with another 25 classrooms.

“That’s a whole elementary school for us,” said Deputy Supt. Norm Anderson.

But there is not enough state facilities funding to meet demands. So far, $227 million has been allocated for early childhood programs; there have been $1.48 billion in requests from school districts for the remaining $369 million. Newsom has proposed delaying another $550 million in state funding for facilities until the 2024-25 budget year.

Enrollment guesswork

Planning for future enrollment has been difficult, administrators said. Even with the best demographers, it’s difficult to know how many families will sign up.

Several districts interviewed reported that they prepared more classrooms than they were able to fill this year.

“After a lot of celebration for getting the legislation passed, we’re making much slower progress than expected. Someone should be worried about that.”

— Bruce Fuller, a UC Berkeley professor of education and public policy

“We still don’t know at the end of the day will we get a lot of 4-year-olds? Or will parents continue to keep them home?” said Fuentes in Pomona. The district has decided not to wait to find out. Next year, Pomona will allow all 4-year-olds to enroll, regardless of birthday, and is adding 11 to 15 classrooms. “Why keep those kids home when they can come and get schooling?” said Fuentes.

The state’s enrollment figures released in April lumped TK and kindergarten enrollment together, but the LAO estimates that just over half of eligible TK students signed up in the first year of the expansion.

Some speculate that many families simply didn’t know their child would be eligible for TK. Districts with limited space or difficulty hiring staff did not advertise as aggressively as they might have. The complex birthday month requirements for eligibility made enrollment confusing.

The Los Angeles Unified School District reports that while enrollment is still below pre-pandemic levels, an additional 1,700 students enrolled in TK and extended TK, the district’s program for younger 4-year-olds.

“We still have some families who are afraid to bring their kids back from the pandemic. Encouraging them to come back, that school is safe and fun, is one of our messages,” said Dean Tagawa, L.A. Unified’s executive director for the Early Childhood Education Division. Like Pomona, L.A. Unified will expand TK to all 4-year-olds.

But while an additional year of free public education may be enticing, many families with 4-year-olds already in care may be hesitant to make a change. “Once you get your child care in place and find a trustworthy and reliable preschool, it takes a lot of flexibility to change your arrangement,” said Fuller, the UC Berkeley professor.

Also, many working parents find half-day TK programs and limited aftercare untenable.

Maryam Moody, a social worker in South San Francisco, decided not to enroll her daughter in TK after learning that the school day ran from 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and aftercare was not available. She would have to pick her daughter up in the middle of the workday and drive her to some other aftercare program, which she would need to pay for separately.

“People are always like, ‘TK is free!’ but it’s only five hours so how would that help me?” Moody says. Instead, she plans to keep her daughter at her current in-home Montessori preschool.

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children, from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.