- Share via

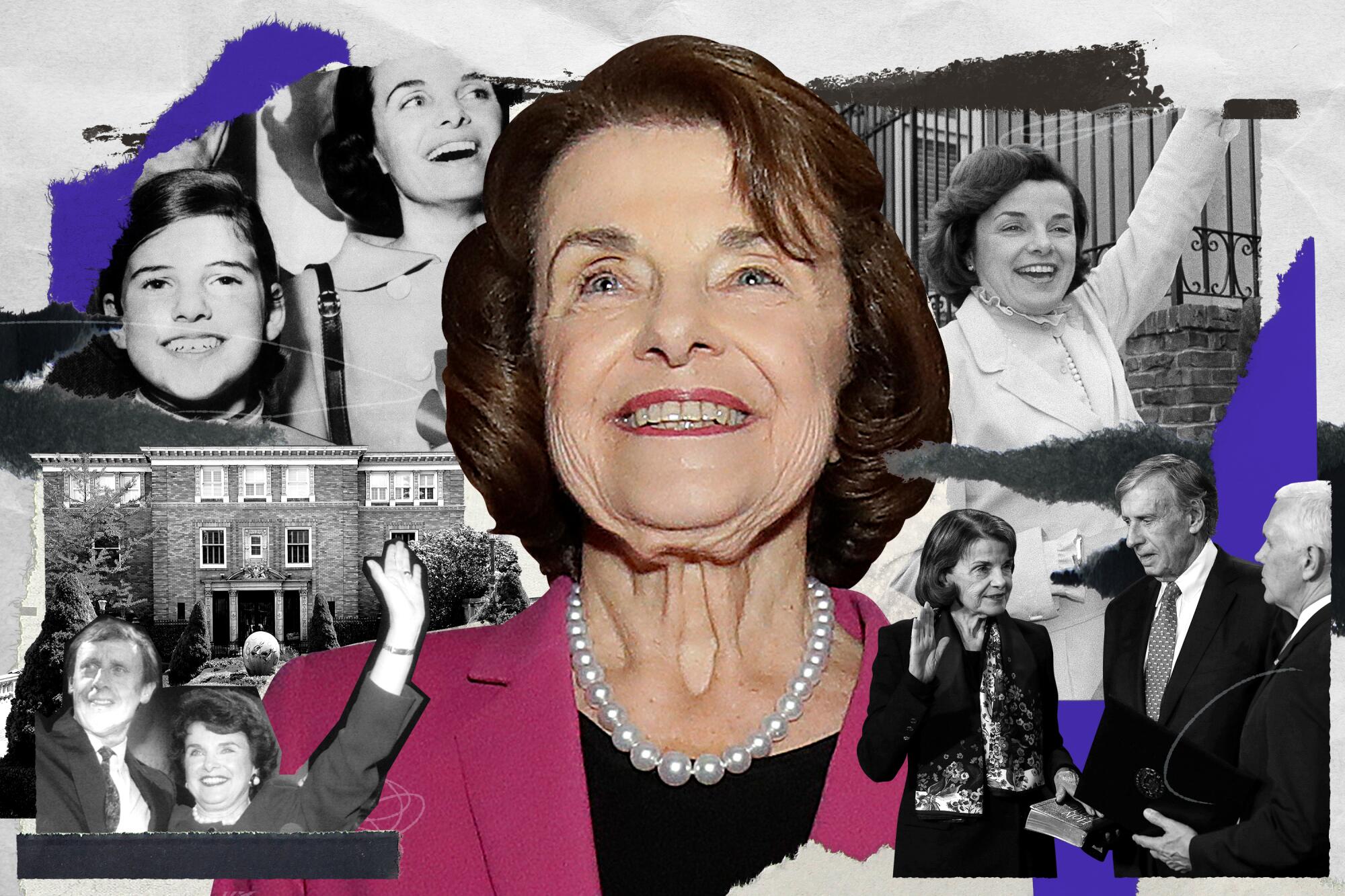

SAN FRANCISCO — One of the great political careers in modern American history began in earnest in a singular moment in 1978, when then-San Francisco Board of Supervisors President Dianne Feinstein showed fortitude in the face of horror.

Announcing that two of her colleagues — Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk — had been assassinated at City Hall, Feinstein was composed and authoritative despite having just borne witness to the bloodshed. So clear was her gravitas — all the more striking in an era of rampant misogyny — that she would use video of herself from that day in later campaign ads.

Nearly half a century later, she is 90 years old, frail and at times forgetful. Her strength is less readily apparent. What abounds instead, at least publicly, is a sense of dissolution — not only of a distinguished political career, but also of her family’s vast fortune and her family itself.

Supporters might have hoped Feinstein’s last chapter in power after 30 years in the U.S. Senate would have buttressed her legacy as a savvy political power broker, but the long farewell has been far from graceful. She is cloistered away from the public when not being prodded into action for brief votes, and is surrounded by a phalanx of defensive aides whenever members of the media approach. In the resulting vacuum of information about the senator’s capabilities and coherence, little is known except her evident decline.

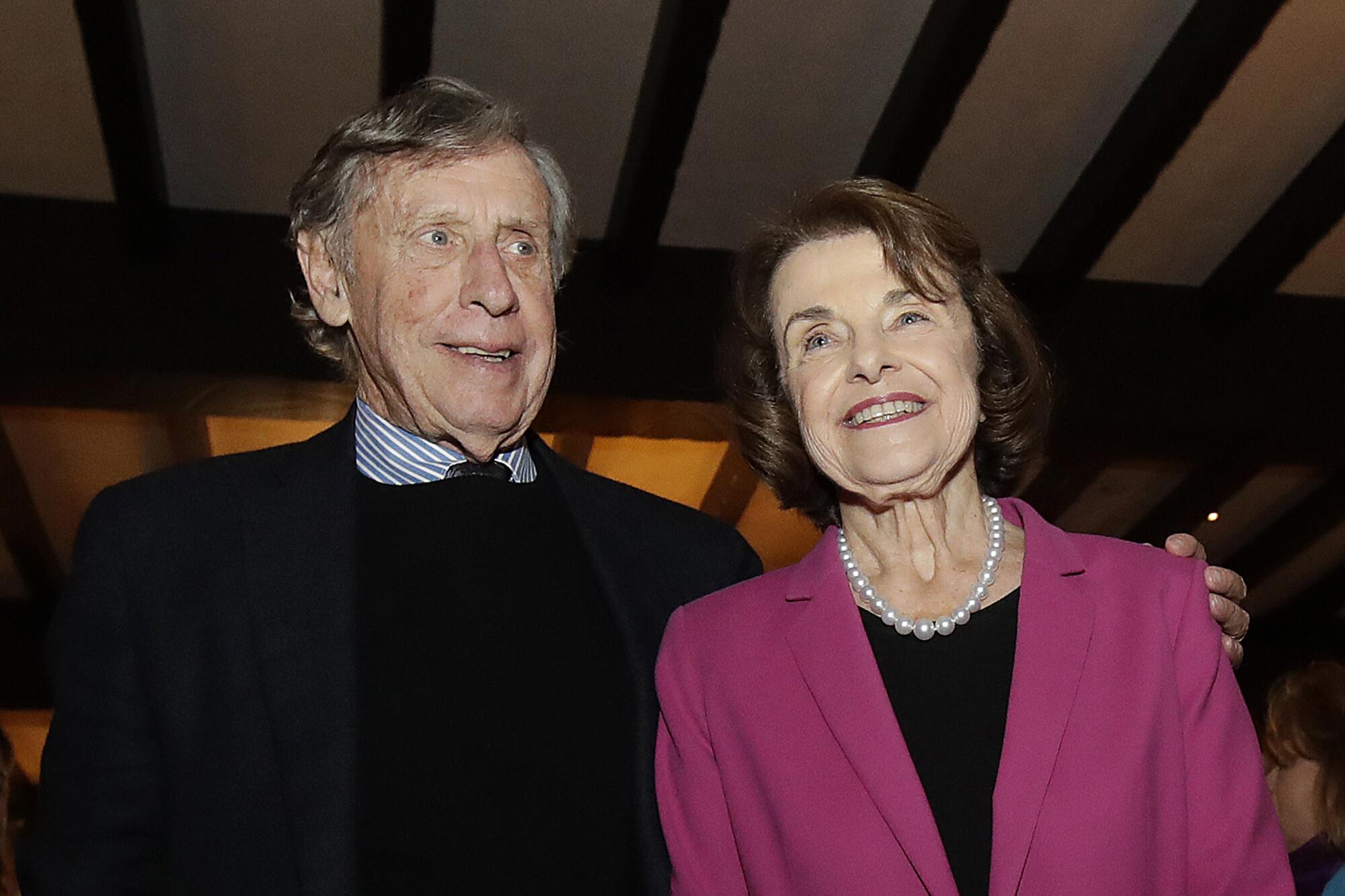

That has been especially true since Feinstein’s frailty became fodder for a family squabble — public for all to see in court filings — over the vast fortune left behind by Feinstein’s late husband Richard Blum, who died last year.

Over the last few months, Feinstein’s daughter from a prior marriage, Katherine Feinstein — a former judge who has power of attorney for her mother in legal matters — has repeatedly sued the trustees assigned to manage Blum’s estate, alleging they have wrongly withheld money owed to her mother for more than a year.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein uses side and back doors to travel the Capitol complex, and a wall of staffers shield her from scrutiny, reports a Times photographer tasked with covering her. But at what cost?

The cases suggest financial friction between Katherine Feinstein and her stepsisters, Blum’s three daughters from a prior marriage, who also stand to benefit from his prosperity. At the crux of the litigation is the senator’s stated desire to gain more control over assets in various Blum trusts and over the couple’s beach house north of San Francisco.

During her long career, Feinstein so meticulously maintained a polished and unflappable public image that journalist and author Jerry Roberts titled his 1994 biography of her “Dianne Feinstein: Never Let Them See You Cry,” based on a piece of advice the senator once gave to other women in the workplace.

Yet now, Feinstein’s personal affairs — including her astounding wealth in a city increasingly derided for its economic disparities and homelessness — have come flooding into public view.

“Sad is exactly the right word for it,” Roberts said in a recent interview.

Katherine Feinstein, speaking exclusively with The Times, said it had been “very emotional.”

“I want my mom to have the most comfortable life she can have, which I believe her husband would have wanted for her,” she said. “I absolutely think she deserves relief from the court. Do I wish it were in the public view? Of course not.”

Family matters

Most Americans are familiar with the tough decisions that can arise when a loved one dies. Few know the sort of wealth being fought over in Feinstein’s case.

Her fortune not only helped forge and sustain her national political career, filling her campaign coffers at key moments, but allowed her life in public service to be appointed lavishly with jets and jewelry and mansions.

Feinstein’s daughter claims in court filings that millions of dollars owed to her mother from the Blum estate have not been disbursed quickly enough, and that her mother needs the money now to pay mounting medical bills.

Feinstein was hospitalized earlier this year with shingles and also suffered from encephalitis, a swelling of the brain. She continues to need care.

Her daughter alleges that in addition to being denied cash payments to the tune of $1.5 million a year as articulated in one of the trusts, Feinstein has been unfairly blocked from selling a multimillion-dollar second home she and Blum shared in a gated community in Stinson Beach, a coveted enclave of waterfront homes north of San Francisco.

Instead, Katherine Feinstein has argued in court filings, her mother has been forced to pay upkeep on the home, which she no longer uses and wants to sell now to “take advantage of the prime selling season for such properties.”

In her interview with The Times, the younger Feinstein said her mother hasn’t been to the Stinson Beach house in several years, has said she will never go there without her late husband, and should be able to sell it.

Alleging that the trustees appointed by Blum are acting in bad faith and failing to fulfill their fiduciary duties, Katherine Feinstein has demanded that they be removed and that more power over the assets be consolidated with her in one instance, and with new trustees appointed by the court in another.

According to the trustees, the suggestion that California’s senior senator is strapped for cash due to medical expenses is bogus.

In a court filing last week, they said Feinstein first reached out to them in June to demand reimbursement for about $169,000 in medical costs, plus trust payments to cover the $9,166 monthly salary of her “security guard and caretaker” moving forward.

The trustees said they had been in the process of assessing Feinstein’s need for such payments in light of her existing “income and means of support,” as required by the terms of the trusts, when her daughter began filing petitions against them in court. As part of their assessment, they said they had determined that the senator has an annual income of about $1 million and a net worth of at least $50 million.

Feinstein’s exact net worth is unclear, and her daughter said it is not as large as some estimates have made it out to be. Still, it is clearly substantial.

When in San Francisco, the senator lives in a three-story mansion on the famous Lyon Street Steps and on the edge of the Presidio. It has sweeping views of the city and surrounding bay, and has been formally assessed at more than $21 million.

When in Washington, Feinstein lives in another grand home assessed at about $7.4 million near the campus of American University.

In addition to those two primary residences, Feinstein has a condominium worth millions on the island of Kauai, Hawaii, and the vacation home in Stinson Beach, which features a stunning deck overlooking the Bolinas Lagoon and is also worth millions.

Environmentalists have criticized Feinstein in the past for flying around the country in her husband’s Gulfstream jet, and the trustees have alleged in the recent litigation that she has slowed their work by not allowing her jewelry collection to be assessed.

The Senate is a club of millionaires, and she is routinely estimated to be among its richest members. Putting Blum’s substantial wealth aside, she is rich in her own right.

As a senator, Feinstein earns a salary of $174,000, and she has a San Francisco pension of nearly $68,000 a year. According to court filings, she has also been receiving disbursements since Blum’s death of $125,000 per quarter, or $500,000 a year, from a separate marital trust.

According to Feinstein’s most recent Senate financial disclosure report, filed in May, she also has various other income sources, including interest on cash holdings in bank accounts.

Feinstein lists a blind trust of her own as being worth $5 million to $25 million; bank accounts containing $6 million to $30 million; and a pension plan worth between $500,000 and $1 million. She has substantial income from interest on those assets and from renting out the Kauai condo.

As a sitting senator, she also has relatively strong health insurance to help cover her medical costs, not to mention access to congressional physicians in Washington.

Katherine Feinstein said in her interview with The Times that if the trustees had simply reimbursed her mother’s medical costs as first requested in June, “this litigation would never have started.”

She said Blum was fully aware of her mother’s independent finances before his death and had nonetheless explicitly stated in his trusts that disbursements should be made to her to ensure her medical needs were met. She also said her mother is fully aware of the litigation and has trusted her to represent her interests in California, including as she heads back to Washington to work.

Many have questioned the senator’s ability to carry out her Senate duties, citing her record of missing votes and her apparent confusion during recent hearings and in brief conversations with reporters. But her daughter said Feinstein remains productive and engaged.

“Every single day, she goes through all her staff memos, and makes notes on them, and either signs off on them or sends them back for changes and additional details,” she said.

“My mother is so driven for work. I wish I could express that. She was born to work. She has always worked — that’s what she wants to do. She wants to go back to the Senate and work,” her daughter said.

“I’ll take care of this in California,” she said of the trust litigation.

Katherine Feinstein declined to answer additional questions from The Times, including about her mother’s health and finances. The San Francisco Chronicle reported Wednesday that the senator confirmed she had asked her daughter to handle the legal matters, after first saying she had not given her permission to “do anything.”

The Feinsteins are not suing the three Blum daughters, but they are implicated by extension as beneficiaries of the trusts, and their rights must also be considered by the trustees.

Blum’s daughters declined to comment, as did their lawyers.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Feinstein’s Senate office declined to make the senator available, and answered a list of specific questions about the trust litigation and the senator’s health with a short statement that said she would not be commenting because these were “private financial and family matters that are not related to Senator Feinstein’s official duties.”

Blum’s trustees declined to comment to The Times, but have been fighting back. In a court filing last week, they accused Katherine Feinstein of trying to “create a media spectacle” by falsely claiming they had denied her mother’s medical needs.

They also questioned how a sitting U.S. senator “supposedly has the capacity to appoint a trustee, yet seemingly cannot file [the resulting litigation] in her own name.”

The trustees’ lawyers have denied any bad faith on the trustees’ part in handling Blum’s estate — which they have said is extremely complex, heavily tied up in investments and difficult to wind down quickly.

“The trustees have acted ethically and appropriately at all times; the same cannot be said for Katherine Feinstein,” attorney Steven P. Braccini wrote in a statement. “This filing is unconscionable. The trustees have always respected Senator Feinstein and always will. But this has nothing to do with her needs and everything to do with her daughter’s avarice.”

A hearing on several of Feinstein’s claims against the trustees is set for Monday before a judge out of San Luis Obispo, according to court filings. Judges in San Francisco, where Katherine Feinstein was on the bench, have recused themselves. Rulings in the matter probably won’t be forthcoming for some time.

Meanwhile, the battle over Blum’s trust is feeding into and becoming intertwined with the broader debate around the senator’s frailty — which has become an important political matter, not just for Feinstein’s personal legacy but for the country.

Political matters

A native of San Francisco born in 1933, Feinstein grew up with two younger sisters under a loving father — who was a successful doctor — and an abusive mother. She attended private schools — Catholic ones, despite being Jewish — and rode horses for recreation.

She graduated from Stanford University in 1955, married Jack Berman — Katherine’s father — in 1956, and divorced him in 1959. In 1962, she married the man whose name she and her daughter would take and keep: neurosurgeon Bertram Feinstein.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

In a video from a local television interview after her first election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1969, the family of three is seen eating breakfast at home, as a domestic employee in an apron serves coffee. The television reporter discusses the couple’s art collections, including one of centuries-old Chinese glazed pottery.

Dr. Feinstein died in 1978. Seven months later, Moscone and Milk were murdered, and Dianne Feinstein became mayor. In 1980, Feinstein married Blum, a fellow native of San Francisco and an investor with an equity management firm and three daughters.

Feinstein served as San Francisco mayor until 1988 and ran unsuccessfully for California governor in 1990. Blum helped bankroll her political aspirations and campaigns along the way, raising questions about his business connections and whether they represented any conflicts of interest for his politically aspirational wife — who in 1992 won the Senate seat she holds to this day.

Throughout her career, Feinstein has been a centrist Democrat whose positions don’t fit into a neat political box. She has championed liberal causes such as LGBTQ+ rights and gun control, but has also bucked the Democratic Party by challenging the Obama administration to publish details on brutal CIA detention and interrogation methods in the post-9/11 era, and by taking what many viewed as a conciliatory approach to confirmation hearings for President Trump’s conservative U.S. Supreme Court nominees.

No one can argue that Feinstein has been anything but a woman of her own mind. She has ruffled feathers and held strong convictions, but has been known for hashing out differences in private rather than public.

“Slightly formal in style, she adheres faithfully to procedure and protocol; she believes in settling disputes privately, and by argument rather than by force,” longtime New Yorker staff writer Connie Bruck wrote in a 2015 piece about Feinstein. “Even in less than momentous situations, she is a dogged negotiator.”

What is left of that famous fortitude is unclear — and that matters politically.

Among other things, Feinstein sits on the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, which approves federal judges put forward by the president. The committee is currently split with 11 Democrats to 10 Republicans. Were Feinstein to resign, Republicans have said they would block the appointment of a Democratic replacement before the next election, leading to a 10-10 stalemate on the committee and disrupting President Biden’s ability to appoint judges.

“There would be a lot of pressure on Republicans to stick with the team, and the argument would be, ‘We don’t want to do anything to let Biden judges get confirmed,’” said UC Berkeley political scientist Eric Schickler.

Family politics

It is impossible for most people to separate Feinstein the person from Feinstein the politician. At times it was hard for her to do, too. Politics and family were always interwoven in the Feinstein household.

Katherine Feinstein has not been shy about the fact that her mother’s career was a strain on their relationship when she was young, but has said they became closer in more recent years.

“Probably as a teenager I was the most resentful of my mother not being like every other mother that I knew at that time,” Katherine Feinstein said in a 2014 NBC interview alongside her mother. “As time has gone on, I think we’ve gotten closer and closer, to the point where no one thinks we are as funny as the other. We spend a lot of really good time just the two of us doing very mundane, regular things that we enjoy immensely.”

Katherine Feinstein and her husband, Rick Mariano, have benefited from generosity on the part of Blum and her mother in the past, and have had successful careers of their own. They live in a San Francisco home assessed at more than $3.6 million.

Feinstein’s relationship with her stepdaughters is less than clear, though was reportedly pleasant.

Based on court filings, it appears each of the Blum sisters had been loaned millions of dollars by their father, and stand to have those loans forgiven, plus millions more given to them, when their father’s trusts are disbursed. They own expensive properties from Santa Monica to Switzerland.

Little is known publicly about the relationship between Katherine Feinstein and the Blum sisters. But experts in trusts and grants said the legal filings in the trust dispute do not suggest a pleasant relationship.

James Creighton, a longtime trust lawyer in California who is not involved in the case, said the apparent lack of communication between the parties outside court, before the litigation was filed, was telling.

Better communication, he said, “could have gone a long way toward resolving this issue, which now has spilled across the national papers in a way that is very embarrassing to all parties.”

Times staff writer Benjamin Oreskes in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.