- Share via

MOSS LANDING, Calif. — The boat sits at the dock waiting to sail. Gleaming under a fresh coat of white paint, black trim and mist-green highlights, it tugs on lines that creak from the marina’s gentle surge.

The captain stands on the flying bridge as the crew casts off. The owner, coffee in hand, watches from the stern railing.

With a straight prow, stolid cabin top, broad aft deck and crow’s nest, the boat, the Western Flyer, is a throwback to the last century — more reminiscent of a child’s toy bobbing in a bathtub’s choppy water than anything taking to the seas today.

By many accounts, today’s outing — a shakedown cruise in local waters — should never have been possible. With nearly nine decades of service on the West Coast, the boat should have slipped beneath the waves long ago. It nearly did.

Striking a reef, it was once pronounced a total loss. Filling with water from a ruptured fish tank, it once nearly swamped. Popping rotten planks, it sank twice at the dock.

Misfortune seemed its destiny, yet still it endured.

“The Western Flyer,” says the owner, John Gregg, “has a life force. All who get on board can feel it.”

Yet Gregg is being disingenuous. Were it not for the $1 million he spent buying the boat — and $6 million restoring it — the Western Flyer would have been lost. But this is more than just an old boat.

Working throttle and rudder, the captain maneuvers away from the dock.

Darwin had the Beagle, Hemingway the Pilar, and for writer John Steinbeck and biologist Ed Ricketts, there was the Western Flyer, hallowed ground for their six-week journey in the spring of 1940 to the Sea of Cortez.

Their sojourn was brief, but their observations of marine life and ruminations on human life — portrayed in Steinbeck’s “The Log from the Sea of Cortez” — have reached across generations, inspiring literary and scientific devotees whose affection for the boat sees value far beyond any modern practicality.

“Being around that boat is like a religious experience even if you are not religious,” said Michael Hemp, a Monterey historian and Cannery Row booster. “You can feel the energy of the people who crowd around it. It’s like being at a football game.”

The captain increases the boat’s speed as it clears the jetty. Monterey Bay, sapphire blue in the morning light, lies ahead.

If the boat is an anachronism, so too is its owner.

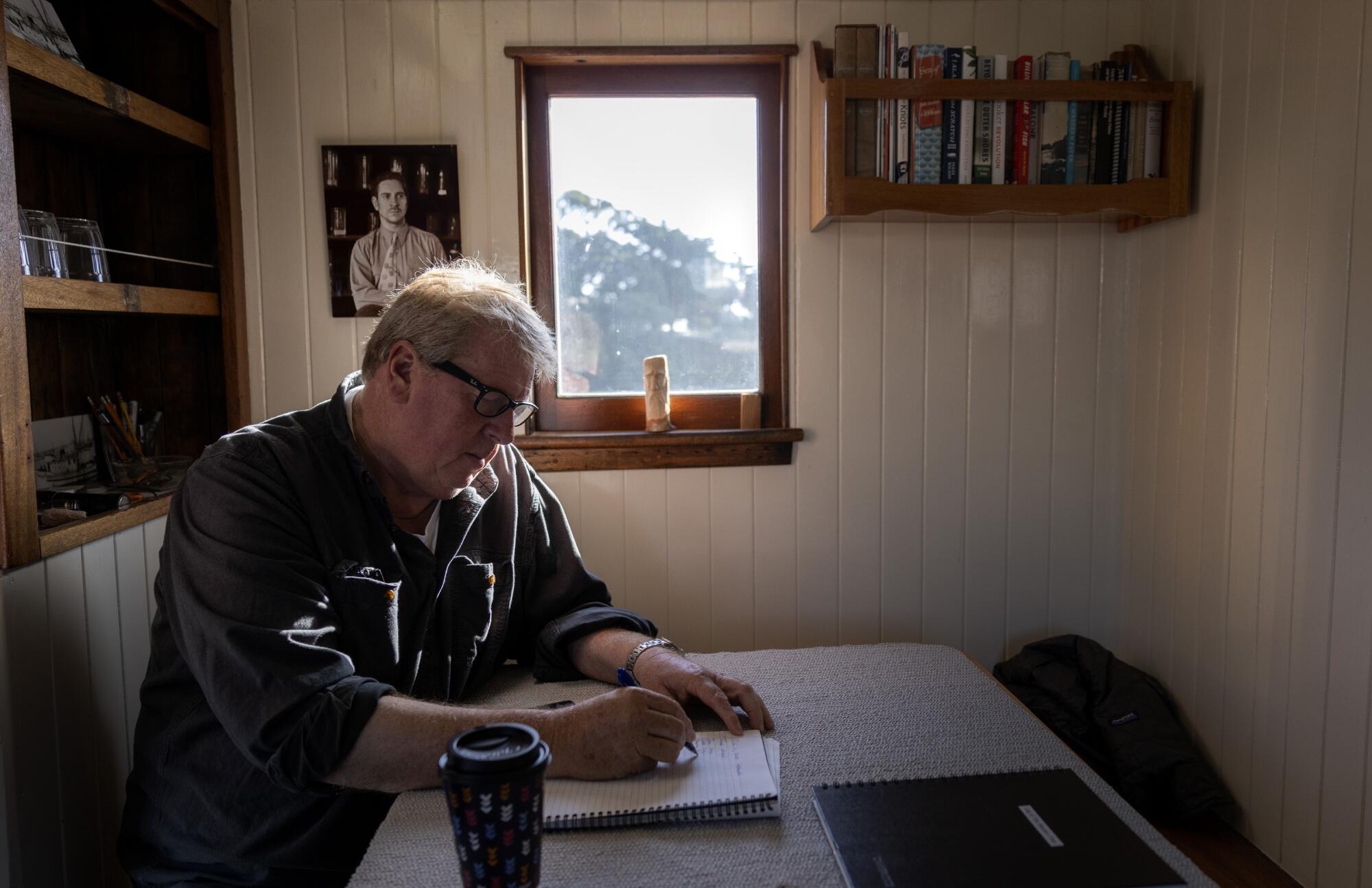

Gregg, 63, is a largely self-taught engineer and scientist, whose curiosities are unbound by any institution or shareholder board.

A geologist, he found his niche in Southern California in the 1980s as a driller, opening a business in Signal Hill and working in the field, splattered by mud as his engines and augers tore into the earth.

Success brought him the wealth, especially when he started working offshore, inventing and selling underwater drilling machines. Today he has the luxury to “follow the radiator cap,” as he puts it, which more often than not takes him up the 101 Freeway from Southern California, where he lives, to Moss Landing.

Childlike in his enthusiasms, Gregg claims just to have “goofed around” to get where he is. The world is his sandbox, he says, perfect for projects that “didn’t make much sense” at the start. Some succeeded; others didn’t. Time will tell which list the Western Flyer is on.

His partner, Renee Ludbrook, thinks of him as a modern Mr. Potts, the inventor from “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.” Together for 22 years, the couple share a home in Corona del Mar.

But rather than developing a flying car, Gregg is looking at the slime produced by hagfish, the antiseptic qualities of horseshoe crab blood, undersea robots and the potential of a sardine boat almost 90 years old.

“He thinks in different patterns than I do,” said Ludbrook. “His brain is always going. I’m never sure what he is thinking of. He is kind of here but often somewhere else.”

What Steinbeck wrote about Ricketts — “His mind had no horizons. He was interested in everything.” — might just as well apply.

Chip away at Gregg’s past, and it may be tempting to connect an avidity for life and brushes with tragedy: a small plane crash he witnessed as a child, its occupants trapped in the flames; the five years he spent at Children’s Hospital of Orange County, where his young son was treated for childhood leukemia. The child survived, but not his marriage.

As much as Gregg believes in science, he keeps a few superstitions as well: putting his left shoe on first, touching the headliner of his truck when he sees a vehicle with one headlight, counting the number of pelicans overhead — and believing that a boat can actually have a life force.

“I have never met anyone like John,” said Douglas Fudge, a professor of biological sciences at Chapman University whose research into the biophysics of hagfish slime has benefited from Gregg’s funding. “A lot of us are in our silos; we think obsessively about the one thing we know about, but John has the ability to make connections that most people would never think of.”

While Gregg knows that the boat’s past is its immediate draw, he hopes its future will be just as bright. He intends to turn the Western Flyer into a classroom for students and a research vessel for scientists.

“There is work to be done,” he says, citing one role for the boat: helping develop wind farms off the California coast.

Just 10 years ago, such a future for the boat would have been impossible.

For the record:

8:57 a.m. Nov. 3, 2023An earlier version of this article misidentified John Steinbeck in a photo caption. He is on the right. Capt. Tony Berry is on the left.

Built in 1937, the 77-foot Western Flyer belongs to a nearly forgotten time when Monterey’s waterfront of honky tonks, flophouses, whorehouses and canneries was supported by a fleet of fishing boats, known as purse seiners for the voluminous nets they deployed, pulling in millions of tons of sardines from local waters until one day they were no more.

Yet, wander the deck or sit in the cabin, and all of that is background for the boat’s grandest adventure: to Baja, where Steinbeck, vilified as a communist, sought to escape the local fury over “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Here he and Ricketts gazed in wonder at the desert and sea. Here they donned rubber boots for collecting forays at low tide, devoured great dishes of spaghetti and watched swordfish “jumping in the afternoon light, flashing like heliographs in the distance.”

And here they imagined a cosmology that encompassed “an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time,” best understood — as Steinbeck wrote — by looking “from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

Afterward came the war, and with the collapse of the sardine fishery the Western Flyer left for the Pacific Northwest, where it chased Pacific perch, red crab and salmon until those harvests also began to decline. Renamed the Gemini, the boat was lost, slowly sliding into anonymous ruin.

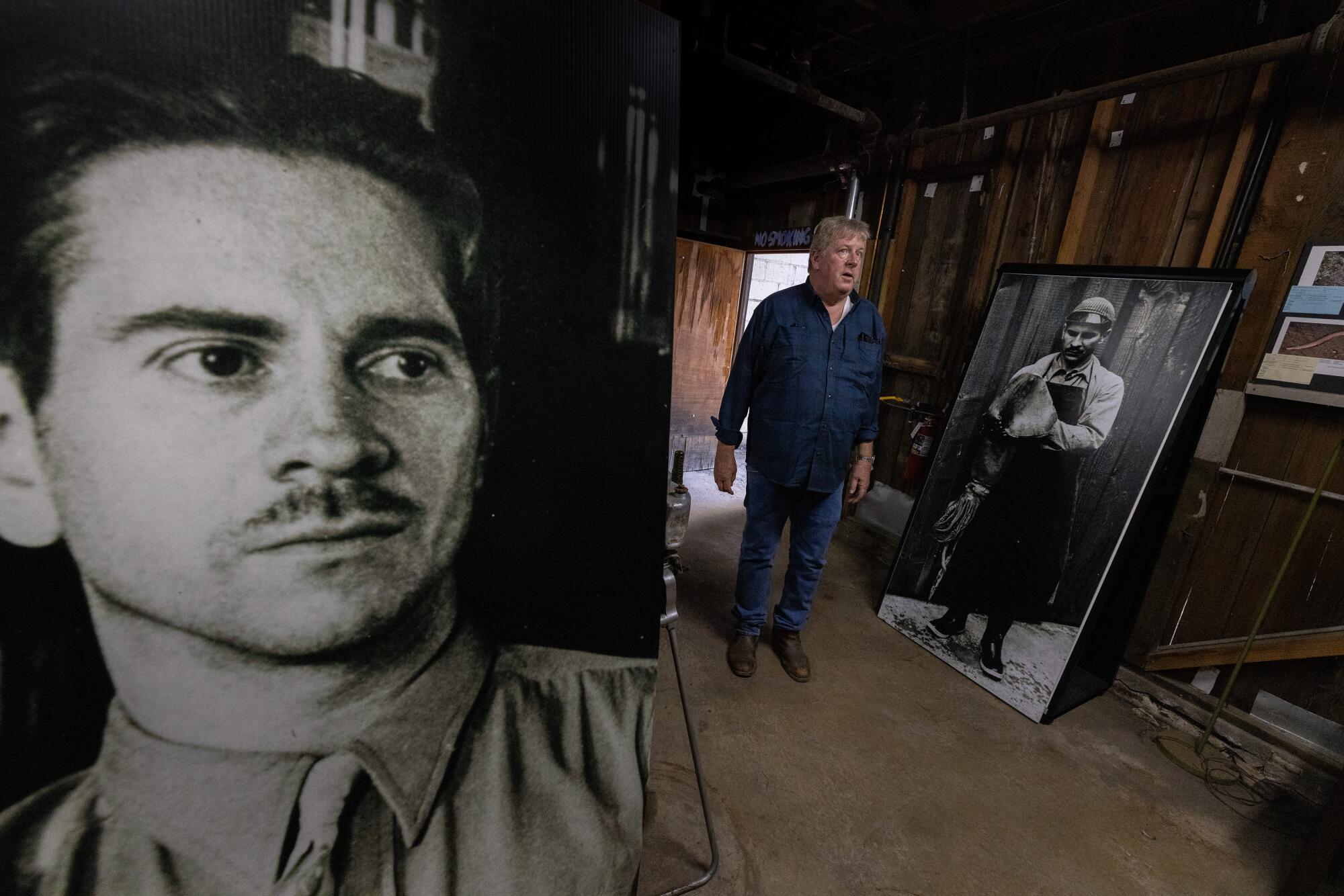

Yet, for a handful of Monterey residents, its memory burned bright. By the 1980s, it had become their Holy Grail, and Bob Enea — nephew of Tony Berry, who piloted the boat through the Sea of Cortez — was their knight errant.

Enea combed through the archives of local papers for news of its whereabouts. He spoke to the old skippers on the wharf, and when his uncle one day recalled the boat’s radio call sign, Whiskey Bravo 4404, he knew the search was over. Names change, but call signs are forever.

He contacted the Coast Guard and traced those letters and numbers to the Gemini. He approached the owner, but the owner didn’t care. He had no interest in selling.

Years later, its ruin nearly complete, the boat was purchased by a real estate developer, whose dream was to chop it up and turn it into a novelty restaurant and bar.

A mile out, the boat rises and lunges through 4-foot swells. The Santa Cruz headlands rise to the west. The wind is at 10 knots, comfortable enough for the crew to stay outside.

Gregg — dark glasses, silver-blond hair, dark chambray shirt, rolled-up sleeves — chats with William Gilly, professor of oceans at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University.

They’re discussing a laboratory that Gilly is building in Baja California Sur that may become one of the Western Flyer’s home ports in Mexico, and Gilly recounts the time almost 20 years ago when he retraced Steinbeck and Ricketts’ journey to the Sea of Cortez, now more commonly called the Gulf of California, in a boat far less comfortable.

Gregg thrives on the passion of others. Years ago, when he read Bruce Chatwin’s “In Patagonia,” he retraced the writer’s 168-mile trek across the pampas of South America to the Cave of the Giant Sloth.

When he heard of a bar in Punta Arenas, Chile, whose ceiling was still splintered by a bullet fired by explorer Ernest Shackleton, he had to see it. Similarly, a broken window in Venice, rumored to have been shattered by Hemingway with a baseball during his wartime convalescence.

Gregg traces his fixation on the Western Flyer to his childhood growing up in coastal Georgia, where the sky was often coursed by contrails from Cape Canaveral. Dreaming of adventure, he read “The Log of the Sea of Cortez,” and while he didn’t understand most of what Steinbeck had written, the book opened a door in his mind that he was unable to close.

Ricketts, he soon realized, was standing at the entrance. “He showed me that you could be a scientist and go to exotic places with your buddies, drink beer and have adventures,” he said. “Wow, this is a job I want.”

Many years later, Gregg visited Monterey. Redevelopment had claimed the waterfront, and he had to crawl under a construction fence to peer up at the weather-worn building where Ricketts, who died in 1948 in a car-train collision, once lived and studied.

Gregg imagined its rooms lit by drink and debate as Steinbeck, Ricketts and mythologist Joseph Campbell hammered out their understanding of the world and the nature of life.

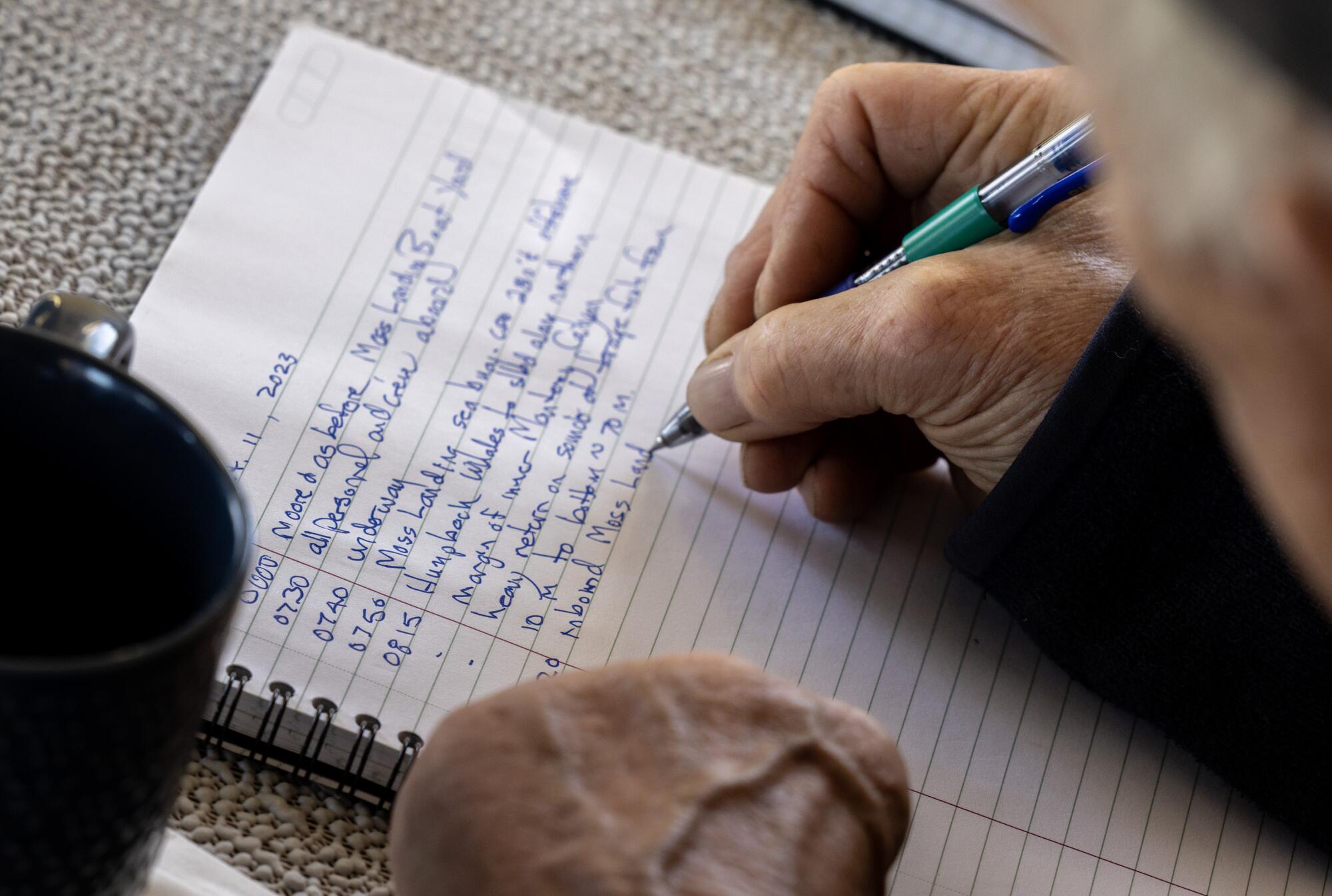

A half-hour out, silver mist of twin whale spouts — humpbacks — fan into the air. The crew — members of the Western Flyer Foundation, a nonprofit Gregg formed in 2016 to support his efforts — fall quiet.

“Never teach over a whale and dolphin sighting,” said Rebecca Mostow, 32, the foundation’s education manager, offering an impromptu rule of the sea. “Sea lions, maybe — but only later in the day.”

Flukes follow, signaling the whales’ dive into the undersea canyon that snakes through the bay.

With rumors spreading about a real estate developer intent on cannibalizing the boat, Gregg stepped in. He hoped for a bargain, but the developer held to his price: $1 million. Gregg saw no alternative and first laid eyes on the Western Flyer in a Port Townsend, Wash., parking lot, propped up by blocks.

Like a zombie, the boat had risen from the dead: rotted wood pocked with barnacles, festered by worms, laced with seaweed. Yet Gregg still was entranced, as a child might be, never imagining that dreams can be real.

Shipwrights spent eight years rebuilding the hull. Piece by piece, they dismantled it and fashioned templates from its planks and ribs, its bulkheads, floorboards and decking for replacements cut from African sipo, Kentucky oak and Douglas fir.

Delayed by the pandemic, frustrated by squabbling among the team and anticipating a cost of $400,000, Gregg knew he had taken on too much, but he never doubted that he would finish this project. Too many people were counting on him (in particular, the self-proclaimed Ed-Heads, for whom Ricketts is something of a high priest).

“My soul is exploding with joy,” said science manager Katie Thomas, 35, who read “The Sea of Cortez” in high school and soon mapped out a career in marine biology. The boat surpasses her expectations.

“It is so quiet; you can talk and hear,” she said. “There is no shouting over the engine and no diesel fumes. I had imagined it would be more crowded, but it feels big and roomy.”

“Now everything comes alive,” Mostow said. “Now we can visualize what we want and can do with students.”

She counts off various projects employing instruments to gauge ocean temperature, salinity and the “pressure of seawater at different depths”; echo-sounding devices to assess “aggregations of fish and zooplankton”; and the ROV, the underwater robot, like a magic carpet “flying around in the water.”

With an estimated operating budget of $2 million a year, the Western Flyer Foundation has been quick to cultivate a fan base for the boat, beginning with a social media campaign that documented the Western Flyer’s reconstruction with a series of YouTube videos with nearly 4 million views. A short film is in the works with actor and woodworker Nick Offerman narrating.

On Nov. 4, the city of Monterey will welcome the Western Flyer with a boat parade to where it will eventually be docked on Fisherman’s Wharf.

Gregg plans to lie low. While most will look for him on the deck of the Western Flyer, he will instead be aboard the Goddess Fantasy, a local whale-watching boat.

As much as he reveres the boat, he understands that it is part of a collective cultural legacy. Napoleon, he said, kept the Mona Lisa in his bedroom for years before having it hung in the Louvre.

“He knew he never owned it,” Gregg said. “He was simply its caretaker.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.