Fears of violence, memories of civil war haunt L.A. Salvadorans over Bukele reelection bid

- Share via

It was a chilly night in Boyle Heights, but the hosts of the “Resistencia Comunitaria” radio show arrived fired up at KQBH 101.5 FM studios, ready to warn Salvadorans that their homeland is once again in very great danger.

“This is a special edition,” announced Karla Cativo, an academic and activist. After greeting her two co-hosts and congratulating a couple of birthday boys, Cativo launched into an impassioned dialogue focused on International Human Rights Day and the 42nd anniversary of the infamous El Mozote massacre in December 1981 that underscored the brutality of U.S.-backed government forces during El Salvador’s 12-year civil war.

“Many of us had to leave because of so much violence. Our lives were exposed to these horrors that we saw in El Mozote and in various parts of El Salvador during the ’70s and ’80s,” said Cativo, who arrived in California with her parents when she was 4 months old, fleeing the war that killed tens of thousands.

It’s a conflict that still echoes among the nearly half-million Southern Californians of Salvadoran descent, and shadows the Central American nation as it slouches toward a critical Feb. 4 general election. Despite a constitutional prohibition, Nayib Bukele, El Salvador’s controversial but highly popular president, is running for a second consecutive term, making him the first person to run for reelection since the dictator Maximiliano Hernández Martínez in 1939.

That’s raising fears among opponents and critics that over the next four years Bukele’s autocratic rule could spark scaled-up violence or even another civil war.

As the hour-long radio program unfolded one recent evening, its hosts mixed protest anthems like “Si me matan,” Silvana Estrada’s homage to Mexico’s femicide victims, and Los de Abajo’s “Resistencia” with pointed commentary about Bukele’s “state of exception,” which has drastically curtailed the country’s brutal criminal mafias but also has resulted unlawful arrests, torture, detentions, disappearances, and extrajudicial killings, according to the U.S. government and human rights groups.

“That is what we are seeing right now,” Cativo continued, “so many arbitrary arrests that are taking place in El Salvador and so many deaths for no reason.”

Co-host Henry Prudencio, 39, chimed in, saying that Bukele’s iron-fisted tactics evoke those of the previous right-wing military government that laid waste to civil liberties 40 years ago.

“Just as they currently do atrocities, the government denies what it does, it denies the deaths. So at first they denied that they had carried out the massacre in El Mozote,” said Prudencio, an actor who came to Los Angeles in 2015 and moonlights as a clown, juggling balls, spikes and clubs at San Fernando Valley intersections.

The stage for Bukele’s potential reelection was set in 2021 when El Salvador’s supreme court deemed that he could run again. That decision was reinforced last month when El Salvador’s Tribunal Supremo Electoral (TSE) accepted his candidacy. Bukele is attempting to steer around the constitutional ban on presidents serving consecutive terms by ostensibly taking a six-month leave, beginning last month, which would allow him to campaign and to retake office in June if he wins the election, as is widely expected.

Salvadorans living in the United States will be able to vote for the third time in a presidential contest, and for the first time also will choose members of Congress.

In 2014 and 2019 the expatriate vote was handled by mail. This time it will take place at 81 electoral centers around the world, including 42 in 30 U.S. cities, including three in Los Angeles, two in San Francisco, and one apiece in Fresno and San Bernardino.

According to the TSE, there are 741,094 expatriates on the electoral registry, many of whom hold a Unique Identity Document that will enable them to use a mobile device or computer to vote starting Jan. 6. Voters with passports will be able to mark their ballots at one of the voting centers.

Politicians in Latin America are adopting Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s style — aviator sunglasses, leather jackets, baseball caps — and his politics.

In October 2022, pro-government legislators approved the Special Law for the Exercise of Suffrage Abroad, which included the online voting modality. Election experts have raised concerns that electronic voting could facilitate manipulation of the result, as some allege occurred during 2021 internal elections by Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party.

Despite the government’s insistence that voting will be fair, Claudia Ortiz, a lawyer and legislator for the opposition party Vamos, believes that the law is flawed.

“There are decisions that show the lack of independence of the TSE,” Ortiz says. “The referee is not impartial.”

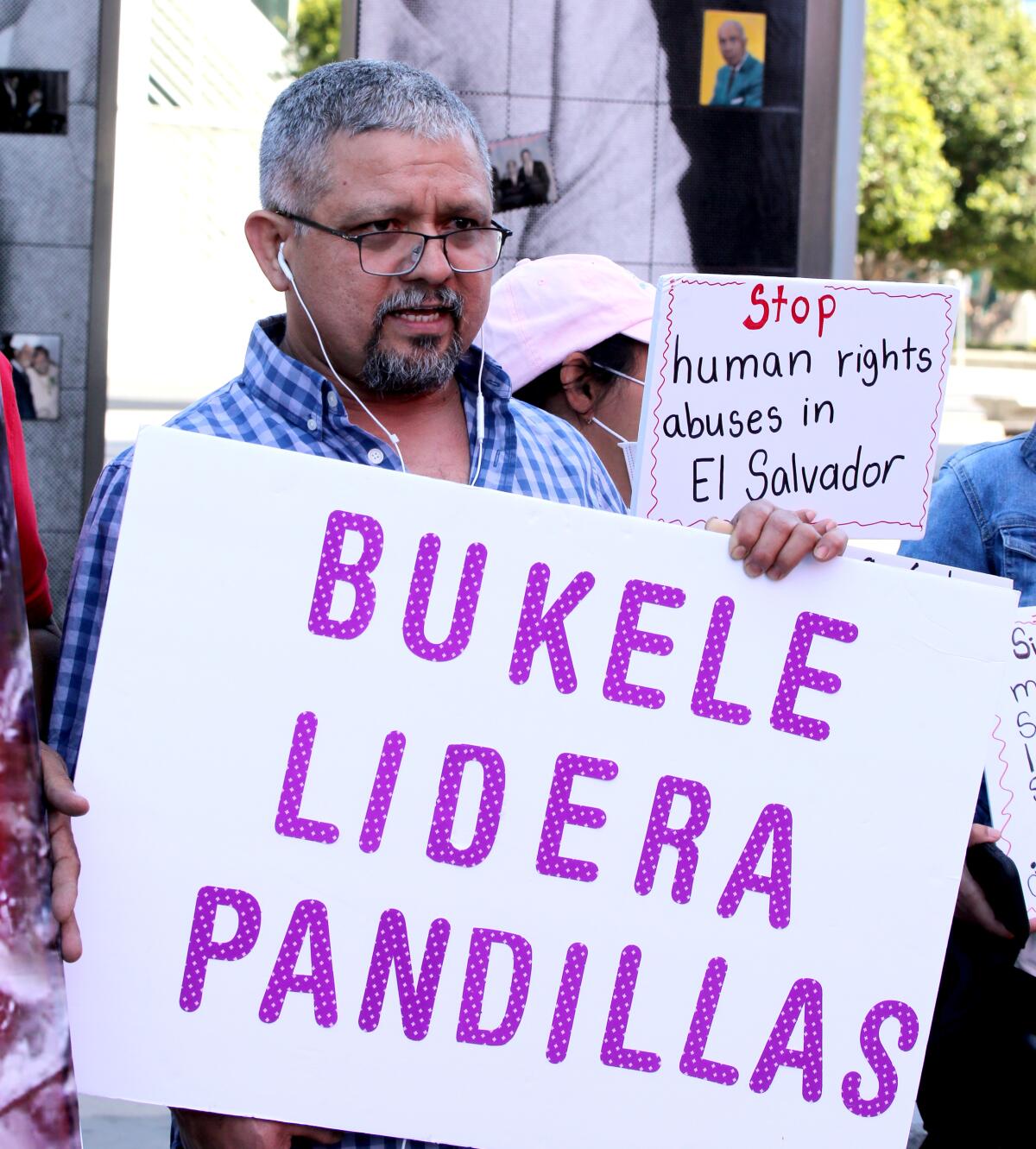

In Los Angeles, Bukele-philes and Bukele-phobes have clashed in recent years during demonstrations and counter-demonstrations at MacArthur Park and elsewhere. Still, Bukele’s support among many Southern Californians remains strong.

Before leaving his native land, Salvador Martínez, an L.A. resident since 1989, had voted for president only once. That was in 1984, when he backed José Napoleón Duarte, the candidate of the Christian Democratic Party, which governed during the civil war’s bloodiest stretch. In February, Martínez plans to cast his ballot for the incumbent president.

“We want the same president to continue governing,” said the mechanic and native of Sonsonate, citing how El Salvador’s homicide rate has plunged under Bukele. “If a government is working well and the people agree, it deserves reelection. It doesn’t matter what the constitution says.”

Although the Biden administration has criticized Bukele’s policies in the past, it has taken a more cautious approach to the prospect of another four years of him. When Brian A. Nichols, undersecretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, visited El Salvador in October, he acknowledged that there could be questions about the “legality and legitimacy” of the pending election.

But he said it was up to the Salvadoran people to determine their next president. Biden has been under increasing pressure to stem the number of immigrants arriving at the U.S. southern border, among them 61,515 Salvadorans who were detained there in fiscal year 2023, according to Customs and Border Protection.

Authoritarianism is spreading across the region, as Daniel Ortega consolidates his grip on Nicaragua, and in Guatemala conservative politicians are working every available lever of government to prevent President-elect Bernardo Arévalo from taking office.

Salvador “Chamba” Sánchez, a former union organizer in his native El Salvador, and now an L.A. political scientist, said that anti-Bukele activists and political adversaries “are on an uphill climb” in opposing the popular president.

“They are wasting their time,” he said. “What the Biden administration wants is stability. It does not care about democracy in El Salvador.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.