A nearly 17-year battle over California medical marijuana dispensary goes up in smoke

- Share via

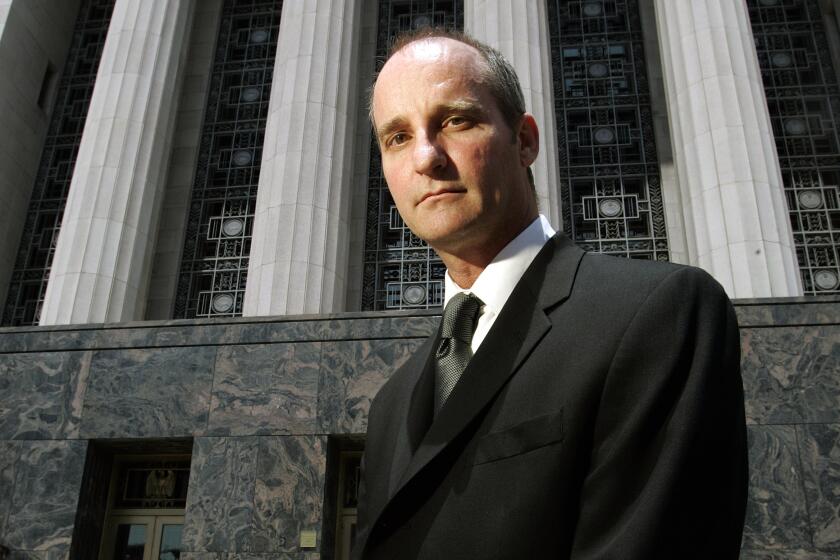

Charles Lynch waited in federal court Thursday — yet another day in a nearly 17-year battle over his former medical marijuana dispensary — surrounded by supporters, including his so-called green team.

Lynch wore an Apple watch with changing backgrounds of his own creation depicting marijuana (including one of the Statue of Liberty smoking a joint). His former secretary at the dispensary wore a marijuana-green blazer. An intentional choice? “You’re g—d— right,” she said.

They were there hoping for an end to a criminal case that had dragged on since Lynch’s arrest on federal charges in 2007. Around noon, they got it.

U.S. District Judge George H. Wu signed off on a diversion agreement that would essentially allow Lynch’s criminal record to be wiped clean in 72 days.

Under the agreement with prosecutors, Lynch’s prior felony convictions for violating federal drug laws would be dismissed in April. He would have no criminal record.

He opened a medical marijuana dispensary in Morro Bay in 2006. The feds shut him down nearly a year later. In 2024, they were still after him.

Outside the courthouse, when asked how he was feeling, Lynch said, “indescribable.”

“It’s been so long, I’ve lost a lot of feeling,” he said, tears in his eyes. “I’ll just wait it out for 72 more days, be a good, law-abiding citizen like I have been for the past 17 years to get to full closure on the case.”

After his arrest, Lynch lost his California home in bankruptcy and eventually moved into a single-wide trailer on his mother’s property in New Mexico. No one would hire him, he said, with “a federal case hanging over my head.”

Asked what was next for him, Lynch said he wasn’t sure.

“There’s talk about me doing new things here in California, but I’m not sure what I want to do yet,” he said. “In a way, I’m a little bit bitter about California leaving me behind for so long. But I’m going to knock that chip off my shoulder and move forward.”

In an emailed statement, Thom Mrozek, a spokesperson for the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles, said office leadership, “believed it was important to resolve this case and focus our resources on the many public safety issues we have been aggressively addressing, including gun crime, fentanyl and methamphetamine trafficking, public corruption, and fraud against vulnerable victims.”

“We believe that the resolution we reached is fair and equitable for all involved,” he wrote.

Reuven Cohen, Lynch’s original federal public defender, wiped away tears of his own Thursday.

“I think a lot of people forgot about Charlie Lynch,” Cohen said. “He took a brave stand 17 years ago on behalf of all of the people who he really wanted to help on the Central Coast.”

In April 2006, Lynch opened a medical marijuana dispensary in the seaside city of Morro Bay. At the time, there were no such dispensaries in San Luis Obispo County.

The mayor, city attorney and members of the Chamber of Commerce were at the ribbon-cutting for the Central Coast Compassionate Caregivers dispensary. A photo captured the mayor shaking Lynch’s hand as he smiled.

Although cultivating, using and selling doctor-recommended medical marijuana was allowed under some circumstances in California, federal law — which is independent of state regulation — bans the drug altogether.

Nearly a year after Lynch opened the dispensary, the Drug Enforcement Administration served a search warrant on the business and his home. Months later, in July 2007, authorities arrested him.

The following year, a jury convicted Lynch on five counts of violating federal drug laws. In June 2009, Wu sentenced Lynch to one year and one day in prison.

After sentencing, Lynch appealed his conviction to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The government cross-appealed, arguing for the five-year mandatory minimum.

In a September 2018 decision, the 9th Circuit upheld Lynch’s conviction. In response to the government’s cross-appeal, it found that Lynch was required to be sentenced to the five-year mandatory minimum.

The panel also noted that a dispute existed as to whether Lynch’s activities were legal under state law. The case was sent back to the district court to make that determination — landing it before Wu once more.

Before the judge could make a ruling after a Jan. 22 hearing, the government offered Lynch a plea deal.

He agreed to plead guilty to misdemeanor possession of marijuana. Prosecutors would recommend a time-served sentence, meaning Lynch wouldn’t spend a day in prison.

On Thursday, the day the plea agreement was set to go before Wu, Lynch waited outside the federal courthouse with his mother, Bodine Jones, and Gina Armstrong, the former secretary of his Morro Bay dispensary.

Also present that day were several members of Lynch’s “green team,” the federal public defenders who had represented him during the lengthy court process.

Jones hadn’t gotten much sleep, she said, thinking about the upcoming day and their future.

“It’s changed our lives over the course of 17 years,” Jones said. She was 67 when everything started. Now, she’s 84.

“I’m glad I’m still standing after all these years,” she said. “Hopefully this is the end, and we can get on with our lives.”

Then came another wrinkle.

According to Cohen, because misdemeanor possession of marijuana is now a pardonable offense, Department of Justice guidelines would not permit a plea to that effect. Instead, the government worked with Lynch to offer a diversion agreement.

By signing the agreement, Lynch conditionally admitted to possession with intent to distribute marijuana. He agreed not to violate any law over the period of diversion and to pay a $2,500 fine. The government would then dismiss everything.

Cohen said he gave “all the credit” to Mack Jenkins, chief of the criminal division, Joseph T. McNally, the first assistant U.S. attorney, and Martin Estrada, the U.S. attorney for the Central District of California.

“Mr. Jenkins showed a lot of class and exercised the kind of judgment that the U.S. attorney’s office can be really proud of,” Cohen said.

Although prosecutors offered a 60-day diversion, Lynch countered with 72 days.

He wanted his record wiped clean April 20.

4/20.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.