Edith Wharton in the time of Trump: a new novel reinvents ‘Ethan Frome’

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Smash-Up

By Ali Benjamin

Random House: 352 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Just in case you’ve forgotten (or possibly blocked out) that semester in high school or college when you read Edith Wharton’s 1911 novella “Ethan Frome,” here is a brief refresher: During a desolate New England winter, a stoic, unhappy man, Ethan, yearns to leave his domineering wife, Zenobia (or Zeena), for her cousin Mattie, who has been living with the couple as Zeena’s aide. After financial circumstances and propriety prevent Ethan and Mattie from running away together, they attempt double suicide by crashing their sled into a tree, so they’d “never have to leave each other any more.” Spoiler alert: The “smash-up,” as it’s referred to, permanently injures Ethan and leaves Mattie paralyzed, bitter and forever dependent on Zeena.

As I reread “Ethan Frome” in preparation for this review, I found myself admiring Wharton’s sumptuous descriptions and her ability to infuse every moment with a sense of inexorable tragedy. But I also wondered: Who the hell would want to retell this story in a contemporary setting?

This is exactly what Ali Benjamin has done with “The Smash-Up,” which takes Wharton’s bleak, turn-of-the-century dirge and updates it to the equally bleak Trump era. It’s September 2018, the Senate is holding a hearing on Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, and Ethan and Zenobia (“Zo”) Frome and their exasperating 11-year-old daughter, Alex, navigate life in Starkfield, Mass.

Drama abounds. The marketing firm Ethan cofounded faces financial ruin due to the sexual misconduct of his former business partner. Zo, a freelance documentary filmmaker, struggles with her latest project while conspiring with her coven, a women’s group called All Them Witches, to protest Kavanaugh’s misogyny. Maddy, the Fromes’ live-in nanny, earns extra money as a cam girl via a gig site called Ten Spot. Alex, prescribed Adderall for an ADD diagnosis, is on the verge of expulsion from her expensive alternative private school. This is white liberal America writ large.

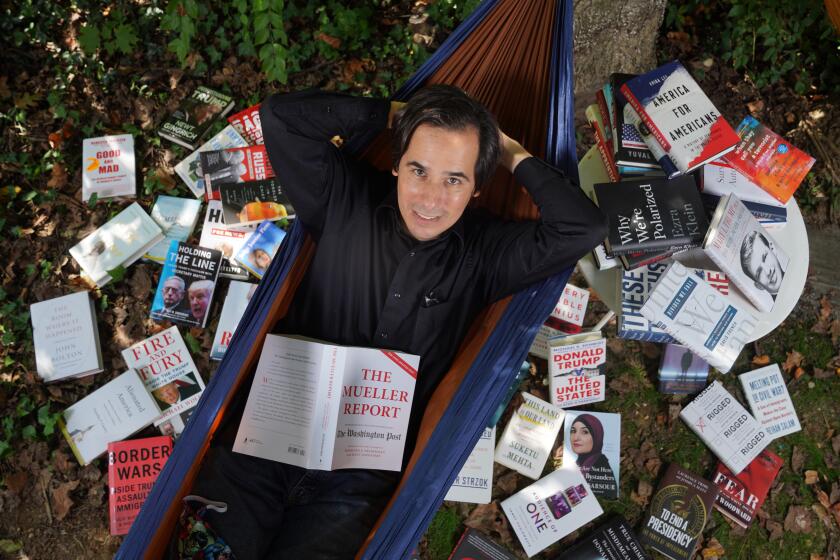

Carlos Lozada read 150 books on Donald Trump for his history, “What Were We Thinking.” He shares surprising insights and lets you know what’s fake news.

As Benjamin wrangles her characters into straits of heightened topicality, she focuses, like Wharton, exclusively on Ethan’s point of view. Through him, we see a culture mired in bewildering metamorphoses about which he remains deeply suspicious. “It’s all outrage these days,” he thinks. “An infinite loop of outrage.” Even in his youth, in the ’90s, he centered himself in the global narrative, seeing the world as unreasonably demanding: “Is he going to have to continue learning the meanings for things, shedding old selves for new, like some sort of molting snake, forever? Does he ever get to simply be?”

The novel nods toward a lot of hot buttons — transphobia, rape culture, hot takes, the whole post-truth smorgasbord — without ever really pushing any. Ethan is meant to typify male fragility but also — as the only character given full interiority — to earn our sympathies (or at least our interest). It is a difficult balancing act, and at times the scales tip toward villainy, as when Ethan crankily dismisses his wife for calling a customer service hotline: “Perhaps the company just advertised on the wrong television show, some cable news outlet whose host said something terrible, or at least clumsily, and someone tweeted it, and now the company’s 1-800 number is fielding furious calls from all over the country.” His disdain can wear out the tolerance of anyone who doesn’t care to spend hours thinking about “cancel culture” one way or the other. Is this really fertile ground for political fiction? Ethan’s not quite a straw man, but occasionally you can’t help thinking: If he only had a brain.

Benjamin litters the novel with heaps of literary allusions and references: Austen, Beckett, Proust, Gogol, Eliot, Rand, Melville, Shakespeare, Stein, Frost, Nabokov, Updike, Wallace, Flaubert — this is a partial list. She is as interested in these authors as she is in Wharton. In fact, one might wonder how Benjamin landed on her particular source text. Couldn’t she engage with all these subjects and allusions and insights without remaking a well-read classic?

The answer to this question is also what makes the novel — for the most part — succeed. It is not the transposition of that well-trod narrative and its character types that compels; it is the contrast sharpened in the act. Wharton’s world is isolated, stifling and dire, and the political implications of her characters’ choices are subtextual. In the polarized, interconnected present of Benjamin’s novel, everything is expressly political, even the ostensibly apolitical.

Yan’s debut novel overturns the tropes of the romance novel in this story about an immigrant’s doomed pursuit of marriage and the American dream.

What this shift sacrifices in symbolic subtlety, it earns back in emotional depth. Wharton’s Zeena remains until the end of “Ethan Frome” a tyrannical spouse whose chronic illnesses are constantly dismissed as hypochondria. Benjamin’s Zo begins in a similar predicament but her human complexities emerge by the end. Ethan too is given not one obstacle to confront but a complex web of them. Like Wharton’s Ethan, he deals with his attraction to a much younger woman who lives in his house, but he also struggles with his daughter’s academic struggles, his business emergency, his stalled career, his suburban neighborhood overrun with wealthy New York expatriates and his withering marriage. Benjamin doesn’t remake “Ethan Frome” so much as she contends with it. “The Smash-Up” is an homage and a critique.

Perhaps the most effective update comes in the conclusion. Benjamin subverts Wharton’s notorious ending in a way that doesn’t just surprise; it complicates. The finale diverges in numerous ways, but one is crucial: who causes the smash-up. In Wharton’s narrative, the effects of a puritanical society work on the characters in spite of their isolation, and the violence is self-inflicted. In “The Smash-Up,” everything seems to be happening to the characters. The violence here is terrorism, and the culprit an incel type whose act ties the narrative into a neat bow, a kind of douche ex machina. It’s an astute commentary on the differences between Wharton’s time and ours, but it also lets the Fromes off a bit lightly. A reader unfamiliar with the source material will inevitably miss out on some of these distinctions, but that’s the price an author pays for literary cosplay.

Some of the novel’s approaches to politics are a bit clumsy or obvious, but that’s often in the nature of political observations: clumsy, obvious truths that are not any less true because they don’t sound original or profound. “The Smash-Up’s” political scope can only make out blurry figures beyond the usual truisms about masculinity and white feminism, but for a narrative focused on its characters’ political and personal myopia, these limitations feel appropriate. Because another unremarkable truth is that all our perspectives are limited; the remarkable tragedy is that these are precisely the limitations we are unable to see.

Maggie O’Farrell uses scant material on the Bard’s family tragedy to examine the struggles of his wife in a beautiful new novel, “Hamnet.”

Clark is the author of “An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom” and the forthcoming “Skateboard.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.