Strike or no strike? All about the Hollywood writers fight that’s just beginning

- Share via

Welcome to the Wide Shot, a newsletter about the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Hollywood’s guard is up for when screenwriters say, “pens down.”

A strike by the Writers Guild of America would probably be the most consequential event of the year in the entertainment industry, coming at a time of upheaval and stress on both sides.

The main sources of tension are well established, even if they haven’t permeated the consciousness of the general public.

Writers are angry that they haven’t received their fair share of riches from the streaming boom, which upended the way the industry operates. Studios, with their parent companies’ stock prices stuck on a multi-year roller coaster ride, have come under pressure to correct for overspending on content that goes to digital video services.

That’s a combustible combination that could result in scribes forming picket lines for the first time in 15 years.

The guild has called on members to grant them the authority to call a work stoppage should they fail to reach an agreement on a new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers by May 1. A strike would halt much of film and TV production nationwide and disrupt a bedrock industry for Southern California and beyond.

Some producers and executives privately acknowledge that the broad contours of the writers complaints — particularly having to do with streaming residuals and so-called mini-rooms — are legitimate and that reasonable heads ought to be able to resolve their differences without undue drama.

And writers aren’t buying the excuse that studio finances are tight. Sure, streaming has thrown the industry’s economics out of whack. But the problem is less about whether Netflix and Apple can afford to pay writers. It has more to do with how companies have deployed excessive capital to nab slashy programming and top-tier creative and acting talent.

So why is there a pervasive feeling that the brewing conflict is a case of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object?

Perhaps aggressive posturing and general anxiety are contributing to a sense of inevitability. Though a strike is not a foregone conclusion, studios have every reason to assume it is and plan accordingly. Better to overprepare and bank scripts for later rather than be caught flatfooted.

The Times’ Company Town team on Monday published a series of pieces analyzing the state of play in the contract talks and the context needed to understand the stakes. Here’s the full package of coverage.

Striking at the heart of Hollywood

— Why Hollywood writers are on edge. Streaming has transformed television and led to a surge in content, but it also has squeezed Hollywood writers. As a strike threat looms, five writers share their stories. For Times subscribers only.

— Lessons learned from 2007-08 strike. The previous writers strike, and lingering mistrust between big media companies and their Hollywood workers, has cast a long shadow over current WGA contract talks.

— A moment of upheaval for the studios. Layoffs, hints of a recession and an uncertain future for streaming add up to contentious negotiations as the WGA looks for a new deal with studios. Not our problem, writers say.

— In past strikes, networks turned to reality TV. Now it’s more complicated. Unscripted programming is once again poised to serve as a stopgap for networks and streaming services, but since the last strike, it has matured into a formidable genre.

(Nonstrike) stuff we wrote

— How did TV cover Trump’s arraignment? It depends on who you watched. TV news coverage of the former president’s arrest had a somber tone. But there were still plenty of partisan jabs on conservative networks Fox News, Newsmax and OAN.

— ‘The Bachelor’s’ crisis over race runs deeper than its creator. As Mike Fleiss departs and the show’s own Black stars publicly demand “accountability,” behind-the-scenes changes point to a franchise at the crossroads.

— She’s seen tragedy and trauma up close. Now Sara Sidner is CNN’s go-to in daytime. The star correspondent joins “CNN News Central,” the network’s attempt to showcase its journalism bona fides to an influential audience.

— Warner Bros. Discovery called out for scrapping Latino programs, CNN cuts post-merger. The cancellation of Latino programming and cuts to CNN were cited by the Democrats, who said the merger is “hollowing out an iconic American studio.”

— ICYMI. Justice Department accuses Activision Blizzard of ‘suppressing’ esports salaries. Fox News settles 2020 election-related defamation suit with Venezuelan businessman. NPR objects to ‘state-affiliated media’ label from Twitter. Don Lemon fires back on ‘15-year-old gossip’ after report alleging misogyny.

Number of the week

Box office results for Universal’s “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” far exceeded expectations with its $204.6 million five-day domestic opening ($146.4 million from Friday through Sunday), delivering another win for producer Chris Meledandri and the growing genre of video game adaptations.

The film’s success also raises the question of why there haven’t been more animated kids movies in theaters lately.

The Illumination Entertainment production likely benefited from a serious dearth of competition, considering that there hasn’t been a major family animated picture in theaters since Dreamworks’ “Puss in Boots: The Last Wish” in December (also a Universal title).

Kids animated fare is expensive and time-consuming for studios, but it can pay off in a big way in theaters. The category has historically been a reliable money-maker for Hollywood. And yet after the pandemic struck, studios were slow to release big animated family-oriented movies even as other genres, like action and horror, surged back to capitalize on the reopening of theaters.

Disney essentially took itself off the board for a while, mostly releasing movies directly to Disney+ and then struggling to recover from that strategy with the commercial disappointments of “Strange World” and “Lightyear.”

The volume of children’s releases is coming back now but is not quite at full strength yet.

This year, there are nine animated family movies on the schedule for wide release, including Easter weekend’s Nintendo-based hit, according to a tally by Boxoffice Pro’s chief analyst, Shawn Robbins. That number could increase throughout the year. In 2019, there were 14 such films that grossed at least $5 million domestically, Robbins said in an email.

Not all of them worked (remember “UglyDolls?” Maybe not.) But that was also the year of “Toy Story 4” and “Frozen II.” It doesn’t hurt anyone to have a couple of those on the books.

Best of the web

— How did these “ugly’ shoes” become so popular? (New York Times)

— Apple wants to solve one of streaming music’s toughest problems. (Wall Street Journal)

— Don’t click this (seriously) unless you’ve already seen Sunday night’s “Succession” episode. (Los Angeles Times)

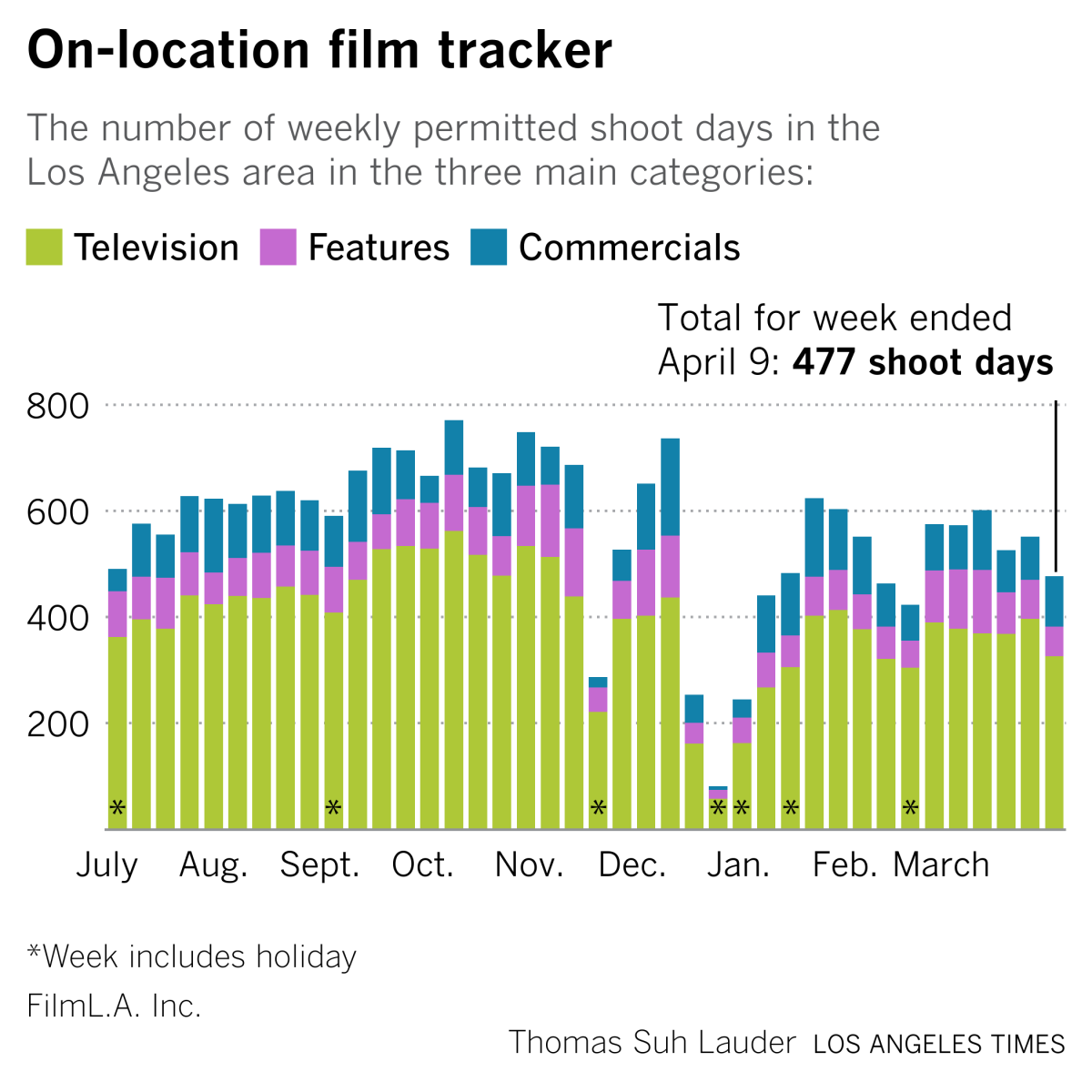

Films shoots

Blame a holiday week for some sluggish production numbers in the L.A. area.

Finally ...

If you are a fan of ’70s rock music, this should definitely be on your list of things to check out.

Producer Burt Sugarman has been putting old clips of classic music TV program “The Midnight Special” on YouTube, featuring performances by Fleetwood Mac, Linda Ronstadt and David Bowie. Stephen Battaglio has the story.

Also, have I mentioned the greatness of the pop group Muna? Here’s its excellent cover of “My Heart Will Go On.”

The Wide Shot is going to Sundance!

We’re sending daily dispatches from Park City throughout the festival’s first weekend. Sign up here for all things Sundance, plus a regular diet of news, analysis and insights on the business of Hollywood, from streaming wars to production.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.