‘Emergency’ fails its characters with a too-safe examination of young Black manhood

- Share via

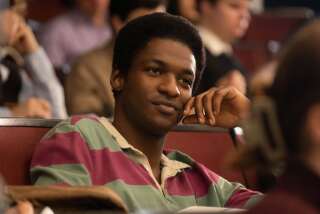

“Don’t get Kunle into any trouble; that boy is Black excellence.” These are the words of caution spoken to Sean (RJ Cyler) during the first act of director Carey Williams’ “Emergency.” They offer not only concern for Kunle (Donald Elise Watkins) — Sean’s best friend, and the more academically inclined of the two Black college students — but a warning to Sean himself: Kunle must be protected, even from you. It is a sentence that plainly communicates the articulations of class and respectability that are mapped on both young men, designating the contrasting boundaries of each boy’s disposability.

This feature-length adaptation of Williams and screenwriter KD Dávila’s 2018 short film of the same name, “Emergency” concerns the majority of its taut runtime with exploring this dynamic. Kunle is a first-generation Nigerian American who hails from a well-off family. Their biggest anxiety about the young man — soon off to Princeton for his graduate studies — is that he is choosing to become the “wrong” type of doctor.

Sean, on the other hand, has little interest in his studies and often finds himself subjected to caring yet patronizing lectures from Kunle regarding his potential. While Kunle is straight-laced and dresses like “a substitute teacher” (a description Cyler delivers with customarily welcome comic relief), Sean is laid back, preferring instead the social scene that college life affords and the welcome comfort of a variety of substances. He also comes from a working-class family that is all too familiar with the ways that Black folks are systematically surveilled and policed in America.

While the differences between the two men seem to be perpetually bubbling under the surface of their relationship and day-to-day interactions, they come to a head when Kunle and Sean return home to their apartment and find an underaged white girl passed out on their living room floor. Frightened and unsure of what to do to both help the girl and keep themselves safe, the film becomes an anxious series of events that unfold alongside the stark realities of Kunle and Sean’s equally converging and disparate experiences as Black men.

What “Emergency” pursues within its college comedy-meets-thriller structure is a treatise on respectability and intercultural discomforts as well as a sober, if occasionally winking, look at the ironies and contradictions of white liberalism. This is patterned with relative degrees of success, with aspects of the film’s outlook hitting on politics that are sometimes all too reductive or simplistic in their delivery — it is a movie that is not only about young people but also feels young in its self-positioning. While too routinely straightforward in both its aims and form, “Emergency” nevertheless reminds us, and Kunle, that respectability and code-switching will not save us; that white womanhood, victimhood and authority can be weaponized against all of us.

“There’s still hope for him” is one of the many barbed refrains throughout the film that refer to Kunle and his assumed bright future. He is not only offered an abundance of hope but also deemed worthy of protection because of it, and indeed much of the plot work that “Emergency” devotes itself to is in service of this. It is a particularly ugly irony that denies Sean the space to refuse his assumed inertness and presupposed lack of future, developing his character instead only in relation to Kunle and his own self-awareness and perception of the world around him. The biggest disappointment of Williams’ film then is not the ordinariness of its style and narrative mechanisms or even its safe and easy politics in search of a similarly broad audience, but its unwillingness to disrupt, with full and heavy weight, the exact things that it critiques.

Emergency

Rated: R, for pervasive language, drug use and some sexual references

Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes

Playing: Streaming on Amazon Prime Video

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.