‘Loving’ documentary doesn’t break much ground on novelist Patricia Highsmith

- Share via

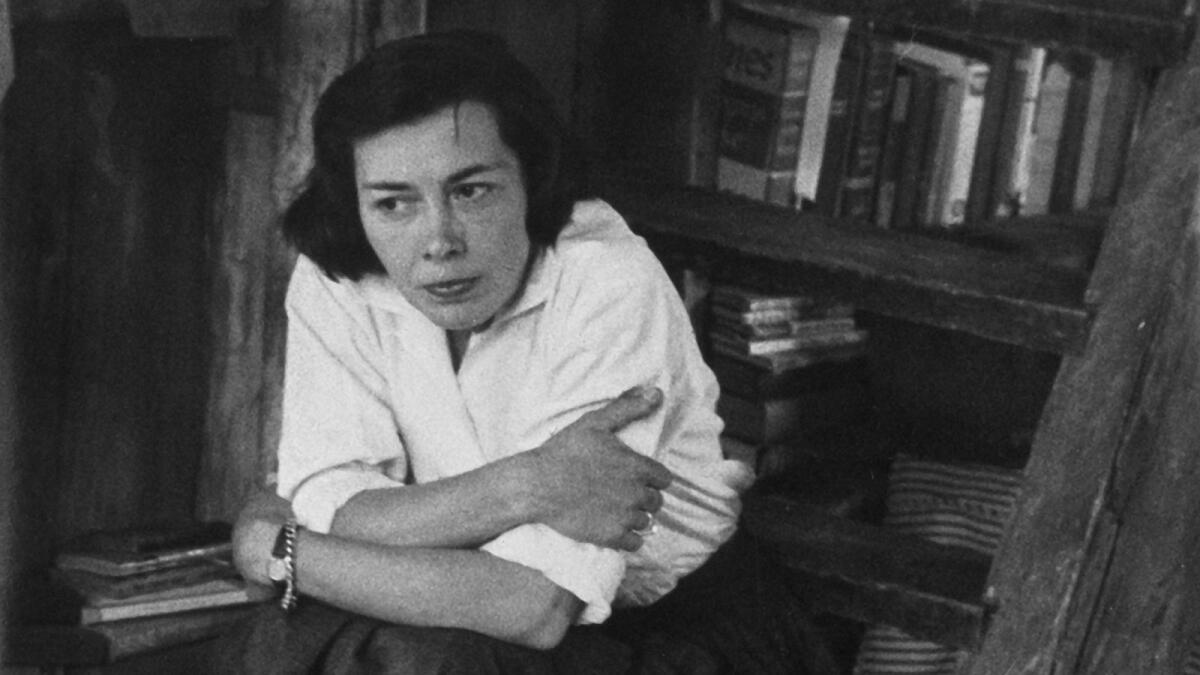

Given that a presence as private and enigmatic as famed suspense author — and unwitting queer icon — Patricia Highsmith may not make for the easiest cinematic dissection, the documentary “Loving Highsmith” earns points for unearthing as much as it does. But that alone isn’t enough to wholly recommend this at times sluggish, elusive look at the groundbreaking force behind such novels as “Strangers on a Train” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley.”

In mapping out the late author’s biography (she died in 1995), writer-director Eva Vitija largely relies on interviews with several onetime lovers of Highsmith, whose life as a mostly-closeted lesbian — particularly during the extra-dicey 1940s and ‘50s — would inform her approach to the world and her writing; there was often a duality and deception to her stories and characters.

For your safety

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the CDC and local health officials.

Romantic partners of Highsmith, such as award-winning American writer Marijane Meaker, who lived with the novelist in the late 1950s, as well as two significantly younger women who first connected with Highsmith in the late 1970s — flamboyant German art-scenester Tabea Blumenschein, who died in 2020, and French teacher-translator Monique Buffet — weigh in with their memories of the often difficult and troubled yet compelling Highsmith. Meaker, now 95, is the bluntest, especially in describing the love-hate relationship between Highsmith and her narcissistic, neglectful mother, Mary. (Her mom admitted to drinking turpentine in an attempt to abort her daughter.)

We also learn that, along with the occasional, unsatisfying forays into sex with men (she even tried gay conversion therapy), Highsmith had a long and ongoing succession of female lovers, including a married woman for whom the writer moved to England. (She dubbed their doomed relationship “sadistic.”) Vitija doesn’t shy away from featuring the complexities of Highsmith’s sexuality, but its darker aspects can feel underexamined.

The same goes for the author’s persona in general. Although archival interview clips show Highsmith as aware and articulate, and her notebook and diary entries, voiced by actress Gwendoline Christie, are vivid (Highsmith called her life “a chronicle of unbelievable mistakes”), references to the writer’s alcoholism, bigotry, isolation, misanthropy and other troubling issues come off more anecdotal than distinguishing. Stronger period context and timeline identifiers would have also helped.

Recent interviews with a trio of the Texas-born Highsmith’s distant relatives — a cousin’s daughter-in-law and her two children — who share photo albums and recall the author from her visits to the Lone Star State, illuminate bits of family history. But deeper knowledge of their renowned relation seems limited.

Where this mosaic-like portrait really falters, though, is in its presentation of Highsmith’s extensive writing output and its myriad film and TV adaptations. Despite spending ample time on her creation of “Strangers on a Train” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” as well as on her 1952 lesbian romance novel “The Price of Salt” (written under a pseudonym but republished in 1990 as “Carol” and finally credited to Highsmith), you wouldn’t quite know from the doc just how widely successful the prolific author was — and for how long.

And, while there are numerous clips from the better-known screen versions of her work — “Strangers,” “Mr. Ripley,” “Carol” — far too many others go unseen. (Snippets of Wim Wenders’ 1977 “The American Friend,” based on her book “Ripley’s Game,” feel oddly slipped in.) Such Highsmith novels as “Deep Water,” “The Two Faces of January” and “The Cry of the Owl” are but a few others that were notably made into pictures — several times each, in fact.

Meanwhile, a frequent use of rodeo imagery may be Vitija’s stab at symbolism but it proves a distracting, head-scratching intrusion on the movie’s compact running time; the calf-tying footage is a bit much.

In addition, input from contemporary LGBTQ and other writers, authors and literary observers might have better fleshed out the film’s social and artistic perspectives.

“Loving Highsmith” is a well-intentioned effort; a respectable start. But perhaps a more definitive and dimensional documentary — or even narrative feature — about this singularly intriguing talent will still be made.

'Loving Highsmith'

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 24 minutes

Playing: Starts Sept. 9, Landmark Nuart Theatre, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.