‘Descendant’ pays powerful witness to the legacy of the slave ship the Clotilda

- Share via

In filmmaker Margaret Brown’s powerfully roiling documentary “Descendant,” submerged history becomes the truth freed for an enclave of Alabamans whose ancestors were the last slaves wrenched to American shores, aboard the Clotilda in 1860.

The operation was illegal at the time, and rumor held that the slave ship’s owner, Timothy Meaher, burned and sank it afterward to hide his crime. Horror was hushed, however, when the only ones keeping the reality of the sin alive for over a century of continued violence and fear were the formerly enslaved themselves and their descendants in Africatown, the Mobile-adjacent community the ship’s survivors founded. Even legendary folklorist Zora Neale Hurston’s 1931 text “Barracoon,” capturing the oral testimony of the long-lived survivor Cudjo Lewis, couldn’t get published until 2018. Its release did spur a newfound search for the Clotilda’s remains, however, which were finally located in the Mobile River in 2019.

“Descendant” brings us to Africatown at this moment of sobering relief and sharper focus for its residents, who have longed for their passed-down memories — the kind Cudjo’s direct descendant Emmett Lewis, a dreadlocked young man with a weary voice, tells us he’s heard and felt his whole life — to be recognized as significant American history.

That shattering past is something Brown, who is from Mobile herself, has explored before in her excellent 2008 documentary, “The Order of Myths,” about her native city’s segregated Mardi Gras celebrations and their ties to the lasting inequality of the powerful Meaher family opposite the struggling Clotilda descendants. Not only does the ship’s discovery erase the need to call it myth, it makes slavery’s reality worth confronting anew as a topic of clarity, memorialization and reparations.

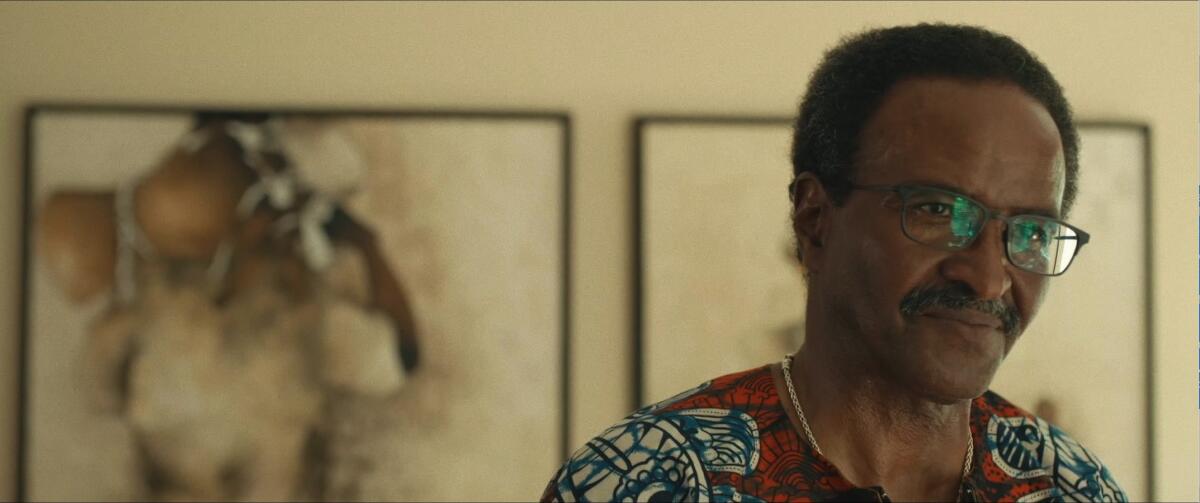

With “Descendant,” Brown wisely chooses to be respectfully, poetically alert instead of imposing, as her use of archival footage shot by Hurston suggests: She’s adding to a pioneering Black filmmaker’s anthropological empathy, updating the conversation, witnessing the witnessers. Brown knows this is not her history to tell but rather an unfolding story about storytelling she can diligently observe in meetings, get-togethers and intimate interviews. From there, the necessary questions about legacy and amends have space to become truly vivid and emotional, articulated as they are by the descendants themselves and supportive figures like Kamau Sadiki, a Smithsonian-affiliated scuba diver specializing in slave wrecks, and environmental justice advocate Ramsey Sprague.

There are grace notes throughout, from descendants reading excerpts from “Barracoon” to the plaintive, roots-tinged score (by Ray Angry, Rhiannon Giddens and Dirk Powell). Repeated images of rippling water don’t only refer to what’s been buried for so long but potently remind us that with past and present, what looks constant is always changing, and vice versa. Brown also frames Africatowners against their surroundings in ways that convey their sturdiness as a tightknit, embattled and resilient community across time.

Even with no Meahers on camera (having refused Brown’s interview requests), their presence seems accurately represented, anyway, in the image of belching smokestacks, a looming background factory or, when descendant Darron Patterson is in midlament for how the Meahers’ rabid, toxic industrialization around them has changed things, the uncanny timing of a logging truck whizzing by. What was an eerie gentility about separate cultures in “The Order of Myths” has been intensified here by a much more starkly delineated, probing and galling portrait of slavery’s ensnarled legacies. (History being inconvenient, an onscreen map notes that the Clotilda slaves came from Dahomey, which would be decades after the abolition-centered events dramatized in the recent hit “The Woman King.”)

Can the Clotilda going from a ghostly marker to a discovery promising renewal finally tip the imbalance of white-suppressed, Black-preserved history toward justice and healing? As we see the residents mix celebration with planning for the future, “Descendant” makes clear how an African American-driven memorial to their experience, enshrined by physical proof, would help correct a dominant, harmful Lost Cause narrative perpetrated for too long on the country’s consciousness.

To descendant Joycelyn Davis, a survivor of the cancer that has plagued so many in Africatown, bitterness about the slave ship’s hold on her community became energetic pride about keeping their history alive. To descendant Veda Tunstall, however, who hears her mother refer to feeling a “completeness,” the threat of further erasure posed by powerful outside opportunists seeking to profit from their community’s potential gives her optimism pause. “I don’t want to be a part of it,” she says about that long overdue restitution. “I want to be it.” What “Descendant” makes painfully clear is that the witnessing must go on.

'Descendant'

Rated: PG, for thematic material, brief language and smoking images

Running time: 1 hour, 49 minutes

Playing: Available Oct. 21 on Netflix

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.