The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

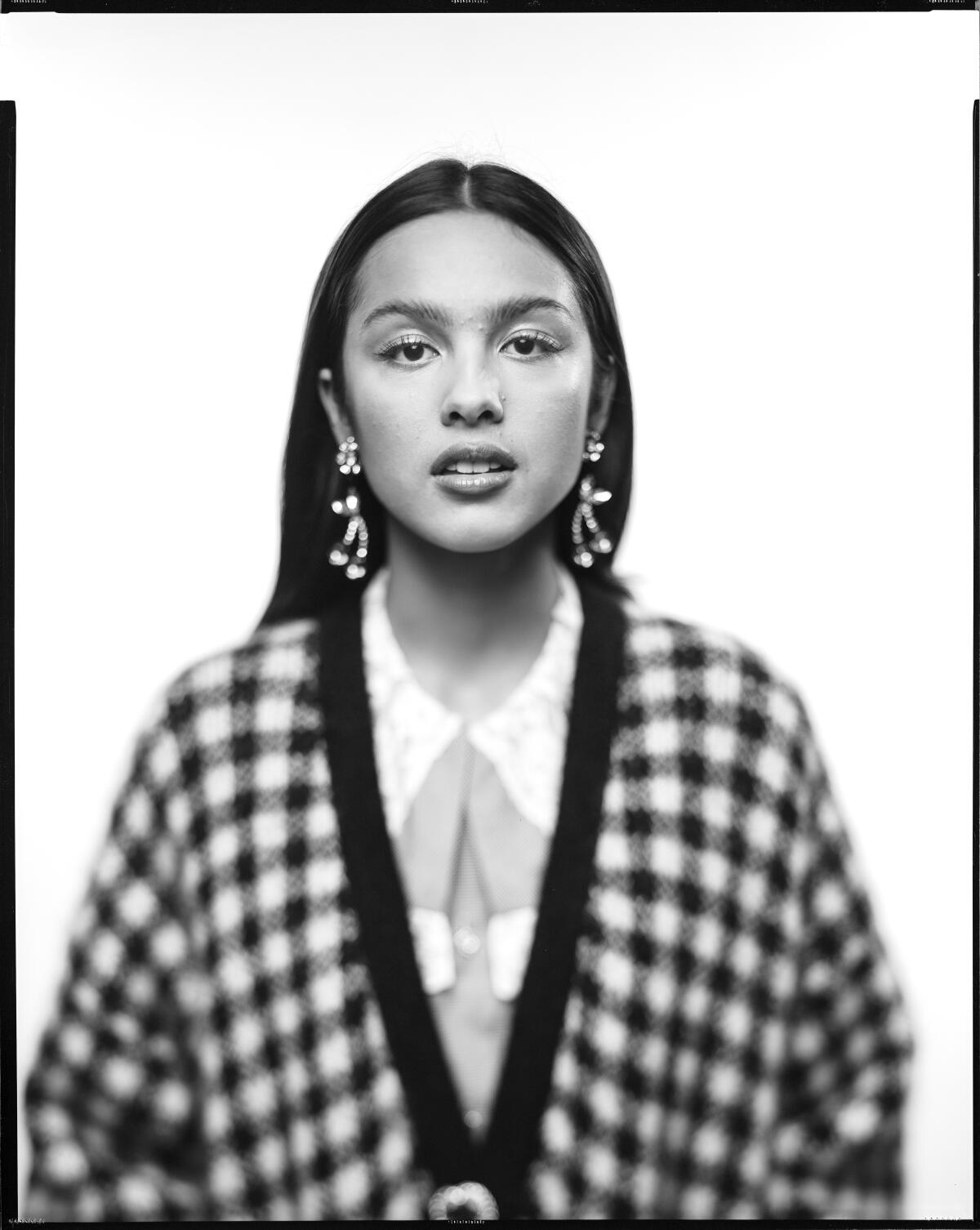

Growing up as a biracial Black and Filipina musician, singer-songwriter H.E.R. could count on a few things her two cultures shared.

“Filipino Americans love R&B like Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston. We love hip-hop and we love a really powerful ballad. There’s always music happening,” the 24-year-old born Gabriella Wilson said, two days before presenting at the Academy Awards and a week before she’s up for album of the year at the 64th Grammys. “I should be careful here, but Filipinos are kind of like the Black people of Asia. I love all our commonalities. When my mom married a Black man, our cultures meshed.”

Amid the pressure on the Grammys to better represent the diversity of who makes and listens to pop music today, this year’s nominations showed one notable flowering of that work: it’s the best year for Filipino Americans in Grammy history.

Will Olivia Rodrigo make history? Could Tony Bennett win for album? Will anyone get slapped? Come Sunday, music’s preeminent awards show takes the spotlight.

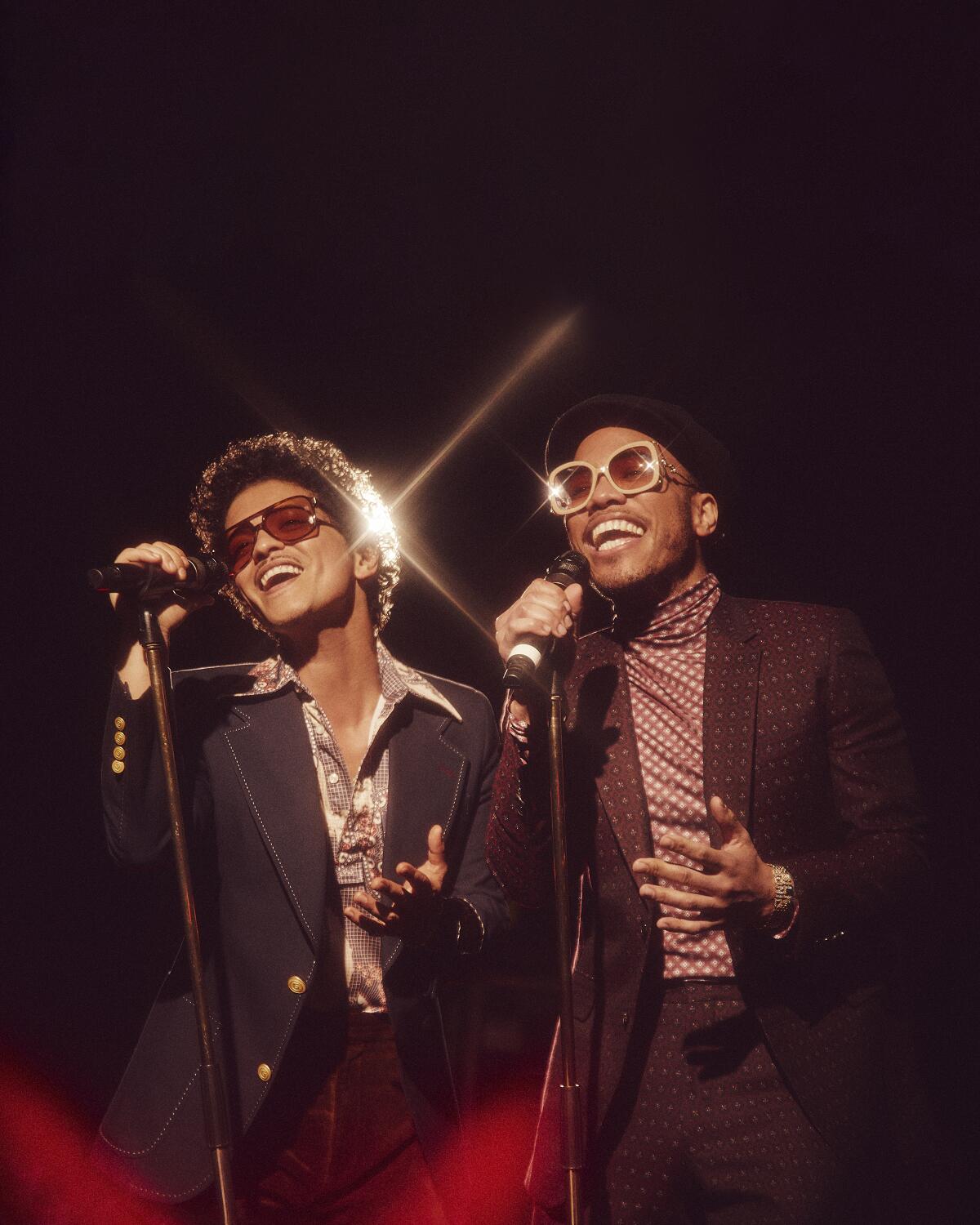

Across top categories, acts with Philippine heritage including Olivia Rodrigo, Saweetie and H.E.R. are up for best new artist and album, song and record of the year prizes. Longtime Grammy favorite Bruno Mars, a multiracial Filipino American Hawaii native, is in contention for four awards with his funk and soul band Silk Sonic, including song and record for “Leave the Door Open.” The Americana singer Elle King, daughter of biracial Filipino American comedian Rob Schneider, is up for country group/duo performance for her duet with Miranda Lambert, “Drunk (and I Don’t Wanna Go Home).” Between them, they have 22 Grammy nominations this year.

All the above acts have multifaceted ethnic backgrounds and arrived at their success through very different genres. (Beyond this year’s Grammys, the Black and Filipino American singer and “Euphoria” star Dominic Fike also enjoyed a breakthrough year.) For the more than 4 million Filipino Americans in the U.S., and especially the 1.6 million in California (where Rodrigo, H.E.R. and Saweetie are from), it’s a moment in the limelight for a tradition of Asian American music culture that’s often blended into other sounds here.

“Within the last couple of years, there’s been a groundswell of Filipino American artists who’ve talked about or embraced their Filipino background more than predecessors like Enrique Iglesias or Nicole Scherzinger,” said James Zarsadiaz, director of the Yuchengco Philippine Studies program at the University of San Francisco. “Artists have been able to talk more freely about how their Filipino backgrounds shape their perspectives or artistry, because Filipinos have truly permeated ‘mainstream’ American culture and consciousness.”

The history of the Philippines and the U.S. has been long and fraught since the colonial era. Control of the Southeast Asian archipelago, formerly a Spanish colony, was contested after the Spanish-American War, and after first declaring independence, the Philippine-American War brought the country under U.S. colonial governance in 1902. At the end of World War II, the Philippines became independent in 1946, though the U.S.’ long military presence there created a complex, charged cultural exchange.

“By that colonial connection, there’s always been a tie between the U.S. and the Philippines that includes music,” Zarsadiaz said. “There’s a power in the diaspora in the notion of ‘kababayan,’ a notion of community and support for fellow Filipinos — they’re one of us, their success is our success.”

Filipino American musicians have, over generations, made an impact on U.S. charts. The explosive R&B singer-dancer Sugar Pie DeSanto toured with James Brown and found national success in the the 1950s and ’60s, and a “Pinoy Rock” movement that riffed on Elvis Presley, American surf and British Invasion sounds became popular in the Philippines at the same time. Broadway performer Lea Salonga was the singing voice for Disney’s Jasmine and Mulan; the Black Eyed Peas’ Apl.De.Ap (born Allan Pineda Lindo) performed on some of the biggest hits of the 2000s, and the actor Darren Criss (who like H.E.R., grew up in the Bay Area) was a heartthrob on “Glee.”

Mars, born Peter Gene Hernandez in Hawaii to a Puerto Rican father and Filipina mother, gave $100,000 to a hurricane relief fund during a 2013 tour stop in Manila, and said onstage, “I’m so proud and so happy to be Filipino.”

“Filipino Americans listen to everything, but culturally are major consumers of hip-hop and R&B. Filipino Americans are often great breakdancers or in dance troupes,” Zarsadiaz said. “It’s not coincidental that a lot of them have origins on West Coast in that multicultural landscape. Hip-hop and R&B are generally seen as pop music among people of color, and for Filipino Americans, it’s part of the soundtrack of their daily lives.”

A year ago, Olivia Rodrigo was a Disney actor with a knack for songwriting. Today, the 18-year-old has 2021’s top debut album and is nominated for 7 Grammys.

Los Angeles has the most Filipino Americans of any U.S. city, with an estimated half-million according to the Pew Research Center. H.E.R. agreed that growing up in California shaped the sense that Black American music had a unique resonance within her Filipino culture too.

“In the Bay Area, you’re forced to know so many different cultures,” she said. “I loved that camaraderie between Black people and Filipino people.”

The rapper Saweetie, who was born Diamonté Quiava Valentin Harper in the Bay Area and graduated from USC, is up for best new artist and rap song for “Best Friend,” with fellow multiracial pop breakthrough Doja Cat. This year’s abundance of Filipino American musicians from the West Coast has already cemented some new friendships between them.

H.E.R. guested on Saweetie’s song “Closer.” “We got to know each other on the video shoot, and even though we have really different sounds we had such a similar story,” H.E.R. said. “It made the world feel smaller.”

Even in farther-flung regions, music could be a tie to a distant Filipino culture. Elle King, of “Ex’s and Oh’s” fame, grew up in Ohio where her main connection to Filipino culture was through her paternal grandmother Pilar, who was born in the Philippines.

“She must have been in her 60s, but she’d fly from San Francisco to Columbus and fly me back for the weekend, it was such dedication of love,” King said. “My Filipino family is deeply rooted in being together. Every house has karaoke, they’re so warm and friendly and don’t care how much of me was Filipina: ‘She’s one of us!’”

The L.A.-raised Olivia Rodrigo is nominated for all four top categories at the Grammys this year, where her range of punky pop and grand balladry made her one of last year’s biggest new acts. The biracial Rodrigo has been outspoken about her Filipina background, and how meaningful it is for her when young Asian Americans see her career as aspirational.

In an email to The Times, Rodrigo said that, “It’s been so amazing to hear, especially from young girls, that they see someone like them out there. Breaking down barriers isn’t just about me, it makes others feel seen as well.”

Touring the Philippines was an important goal for her post-Grammy return to the road.

“I hope to visit the Philippines someday,” Rodrigo said. “It would be exciting to perform for my Filipino fans and experience the culture in a way that I have not before.”

Now that so many Filipino American artists have hit the top rungs of Grammy fame, Zarsadiaz is curious about what the next stages of engagement with that culture will look like. While K-pop arrived in the U.S. over the last decade with an established infrastructure, Filipino musicians in the U.S. were often raised on popular American genres.

While the country’s distinct culinary excellence has flourished in L.A., Zarsadiaz thinks it’s a more complicated path for overtly “Filipino” music to rise here in the way K-Pop did.

“K-pop grounded itself as trendy, because there was an aesthetic and fashion and fandom tied to that presentation,” he said. “Filipino Americans, often if they grew up here, were told to embrace an American identity, to assimilate, and part of that was embracing the English language more.

“But what I’ve noticed with singers, when I read interviews, they sprinkle in references about Filipino-ness,” he continued. “I don’t really see any of those Grammy-nominated artists doing a Tagalog album anytime soon, but it’s not tied to embarrassment — it’s about having a wide enough consciousness of what it means to be Filipino in America.”

For this year’s Grammy crop, that might mean a Tagalog shout-out in an acceptance speech, or other ways to demonstrate “kababayan” while navigating broader trends in American pop music. After Trump and the protests of 2020, many artists feel a fresh urgency to talk about race and how it affects them.

King admits that she’s “not very good at making adobo or lumpia; I’m a little Filipina and a whole lot of hillbilly,” she said. But on her first trip to the Philippines recently, “If they know you have any amount of it in you, since I’m the daughter of a well-known Filipino, I felt so welcomed. I played a show there and it made me proud to make it to Manila where my grandma came from. It’s so wonderful to see all our children who get to grow up together and pass that on.”

H.E.R. added that, especially for Black and Filipino young people, “Color-ist beauty standards could make you not proud of where you’re from,” she said. “Now, we can more openly appreciate those differences and diversity and celebrate those skin tones.

“We’re becoming the people we wanted to see growing up.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.